A super exciting discovery

In October 2020, a remarkable discovery was made that completely escaped my notice at the time - I was busy starting my masters' degree, trying to manage the (very heavy) workload we were all hit with from the word go, because this is Oxford we're talking about after all, and the news was dominated by the Coronavirus pandemic. In a field in Berkshire, just south of Marlow-on-Thames, where two years earlier ancient bronze bowls had been discovered by metal detectorists, archaeologists unearthed the skeleton of a sixth century man buried with various weapons, including spears and a sword in its scabbard.

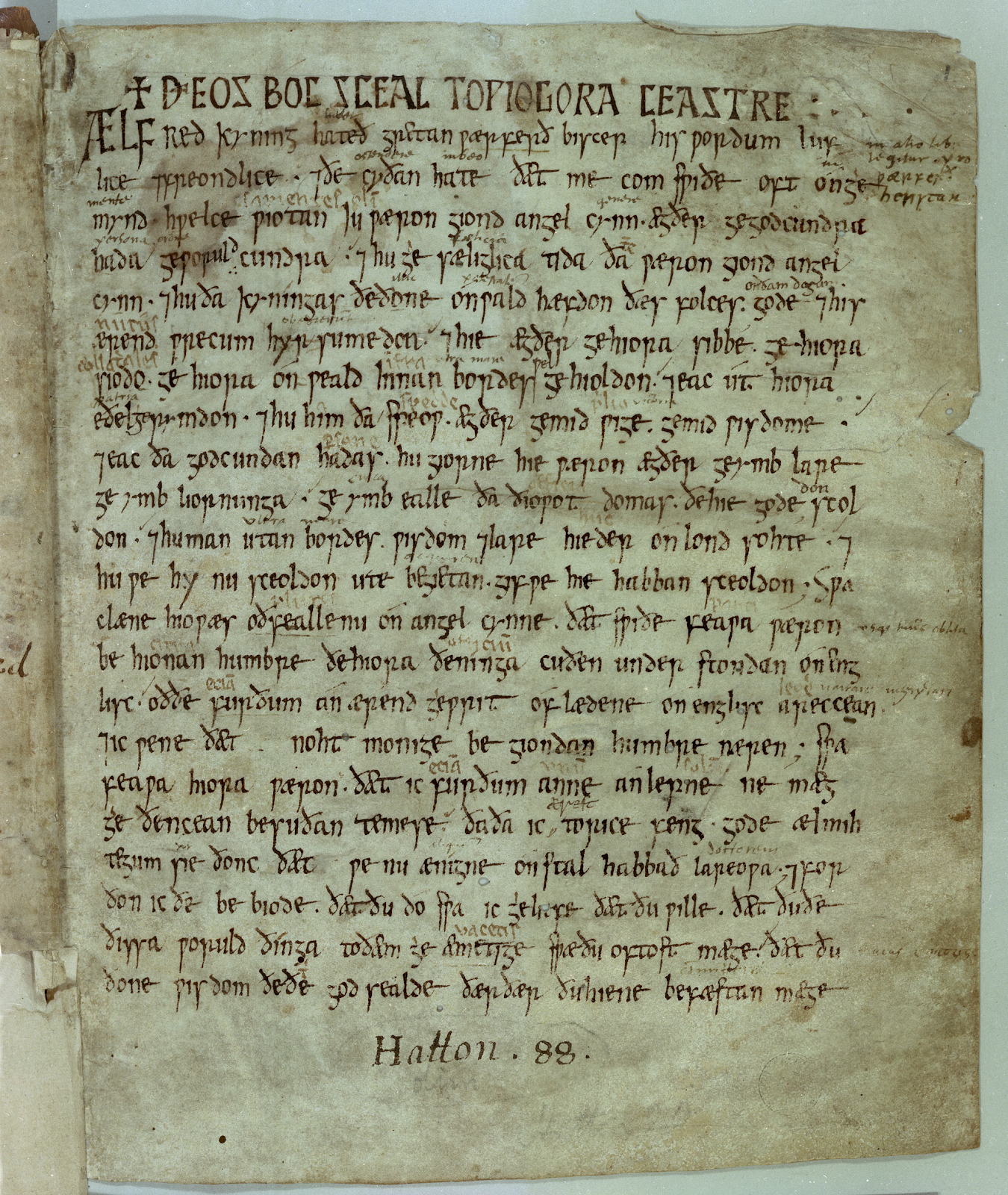

|

| Fairly self-explanatory what this is |

|

| Ditto that |

|

| The middle Thames Valley, the area in question, with the location of the find clearly highlighted |

Subsequent osteoarchaeological analysis showed that this man was six feet tall - the average adult male height in Britain from c.450 - 700 was five foot seven inches, equivalent to that in the first half the twentieth century (two inches shorter than the average adult male height in the UK today) - and had well-developed muscles, clear signs that he was quite a physically impressive and imposing specimen at the time. comparable to Dr Gabor Thomas, a medieval archaeologist from the University of Reading, describes him thus: "the word that comes to mind is pretty butch." I would add that in a world long before professional body-building, steroids and creatine, his contemporaries certainly wouldn't have said anything less about him. At this stage, the age at which this man died, or his cause of death remain unknown, though Thomas himself suspects he was probably in his thirties when he died. However, from the osteoarchaeological analysis, the team of archaeologists at the University of Reading found that his teeth showed signs of wear and that he was starting to develop arthritis. What we can therefore deduce is that while in many respects he was a healthy individual, being tall and muscular and all that, he did suffer from some forms of long-term chronic stress. The wear on his teeth (what is technically called dental enamel hypoplasia) is a good indication of that, as Robin Fleming points out in her absolutely excellent introduction to what skeletons can tell us about the lives of individuals roughly a millennium and a half ago, "Bones for Historians: Putting the Body back into Biography" in David Bates, Julia Crick and Sarah Hamilton (eds), "Writing Medieval Biography, 750 - 1250: Essays in honour of Frank Barlow", pp 29 - 48. Fleming reminds us that since your tooth tissue is not remoulded during life - as soon as you lose your milk teeth and get your adult teeth, the tissue stays the same - worn enamel on teeth can serve as an indication of bouts of ill-health as a child. Fleming also describes a certain paradox - skeletons that show signs of stress are not necessarily those of most sickly and vulnerable people in their communities. Good quality skeletons not marked by signs of stress tend to be those of people who died early and swiftly. By contrast, skeletons that show signs of stress tend to be those of people who were hearty and hale enough to survive their illnesses, at least for the duration of time needed for for signs of stress to be visible on their bones. At the same time, she also demonstrates, based from the trends across the broad range of fifth to seventh century cemeteries in England she has studied, that individuals whose skeletons show signs of stress on the whole had shorter lives, because their immune systems were drastically weakened by stress from past illnesses. She points to how individuals with a single episode of dental hypoplasia died five and half years earlier on average than those with none and those with two episodes died eight years earlier on average than those with none. With all these things considered, we have a lot of mixed signals from this man's skeleton, which is presumably why Dr Thomas thinks that he died sometime in his thirties, on the cusp of middle age.

But this is osteoarchaeological stuff I'm absolutely not qualified to talk about aside, I'm going to move on to some things I'm slightly more qualified to talk about (I will remind you here that I didn't do British History Paper 1 at Oxford, so insular history before 1042 is a comparatively weak area for me, despite that being quite inconsistent with my blogging record here). Those are the implications of this for our understanding of what the hell was going on in Britain in the post-Roman period, lets say from roughly the withdrawal of the Roman legions from Britain c.410 and the Synod of Whitby c.664, which saw the triumph of Roman Christianity over Celtic Christianity in the now fully-fledged Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

A super boring yet necessary crash course on the political historiography of post-Roman Britain

All of the post-Roman period in Britain up until the turn of the seventh century is notoriously difficult period in terms of sources. We do have an abundance of archaeological material, that keeps growing year on year and from which we can infer a lot about the material culture, the landscape, the economy (wealth, standards of living, trade links etc) and even a bit about social structure. But written records are incredibly sparse for this period, even by the standards of post-Roman Europe. Nearly all of them emanate from the western part of the British Isles, and are limited to some inscriptions, St Patrick's fifth century Confession and Letter to Coroticus, a hell fire sermon by a Welsh priest called Gildas dated to c.550 and some late sixth century land grants from south Wales. Gildas and Patrick's writings focus mainly on the religious world and morality. Yet Patrick's Letter to Coroticus concerns the excommunication of a slave-raiding warlord operating in the Irish Sea area, while Gildas describes Saxon invasions, their setbacks at the hands of a heroic general called Aurelius Ambrosius, various battles including Badon Hill (later associated with King Arthur) and the Romano-Britons being ruled by many petty kings, including a "proud tyrant" thought to be Vortigern (one of the villains of Geoffrey of Monmouth's twelfth century History of the Kings of Britain - the foundation of Arthurian lore). Thus they seem, at least on the surface,Continental observers don't provide us with much help either. After the life of St Germanus of Auxerre (d.448), written c.480 by Constantius of Lyon, which does recount the Saint's visit to the former Roman province of Britannia in 429 - 430, which does describe the saint leading an army of Romano-Britons to victory over an army of Picts and Saxons but presents all kinds of difficulties of interpretation, most continental writers take no interest in Britain at all. The great writers of the sixth century West, the likes of Cassiodorus and Gregory of Tours, say virtually nothing of the British Isles. Procopius of Caesarea, the prolific sixth century East Roman historian, does have something to say about sixth century Britain (History of the wars, 8.20.6-10) here:

Three very populous nations inhabit the Island of Brittia, and one king is set over each of them. And the names of these nations are Angles, Frisians, and Britons who have the same name as the island. So great apparently is the multitude of these peoples that every year in large groups they migrate from there with their women and children and go to the Franks. And they [the Franks] are settling them in what seems to be the more desolate part of their land, and as a result of this they say they are gaining possession of the island. So that not long ago the king of the Franks actually sent some of his friends to the Emperor Justinian in Byzantium, and despatched with them the men of the Angles, claiming that this island [Britain], too, is ruled by him. Such then are the matters concerning the island called Brittia.

None of this sounds remotely plausible and it only gets weirder from there. Elsewhere (History of the Wars, 8.20.42-48), he says that:

Now in this island of Britain the men of ancient times built a long wall, cutting off a large part of it; and the climate and the soil and everything else is not alike on the two sides of it. For to the south of the wall there is a salubrious air, changing with the seasons, being moderately warm in summer and cool in winter. But on the north side everything is the reverse of this, so that it is actually impossible for a man to survive there even a half-hour, but countless snakes and serpents and every other kind of wild creature occupy this area as their own. And, strangest of all, the inhabitants say that if a man crosses this wall and goes to the other side, he dies straightway. They say, then, that the souls of men who die are always conveyed to this place.

Now you might be thinking, what the hell is going on here! How could Procopius forget that it was his own people, the Romans, who built Hadrian's wall (literally named after the Emperor Hadrian) and that the area beyond it had human habitation, albeit by barbarous Pictish tribes? Of course, elsewhere Procopius expresses his scepticism about these garbled, second hand accounts brought to him via barbarian travellers, and in the original Greek he distinguishes between Bretania and Brittia. Guy Halsall thinks the former denotes between the historical Roman province and the latter this terra incognita it has now become. In other words, according to Halsall, Procopius recounts these strange fairy tales as a really clever, ironic way of demonstrating that he can't ascertain any reliable knowledge about the island at all, that its completely fallen off the Roman map and its own inhabitants and near-neighbours tell you such strange and barely credible stories about it that you cannot believe it to be the same place as the former civilised Roman province. This is all in spite of the enduring trade links between the East Romans and the former imperial province.

So, if you're going to write a political history of Britain in the period c.450 - 600, what sources do you use? There are of course later, fully fleshed-out narrative account by Anglo-Saxon and Welsh authors - the Ecclesiastical History of the English People by Bede (c.731), the History of the Britons by Nennius (c.830), the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (begun c.890) and the Annals of Wales (tenth century). From the great pioneers of English national history, William of Malmesbury and Henry of Huntingdon, in the twelfth century until late-into the twentieth, these sources have been presumed to provide an essentially accurate account, albeit with errors and inconsistencies here and there (which William of Malmesbury and Henry of Huntingdon were good at spotting) of what happened in his period.

The story they tell is the one most historically-aware people in the UK are familiar with, which goes thus. In 410 AD the Western Roman Empire, beset by barbarian invasions and civil war, decides that it can no longer defend Britain any more, and the Roman legions withdraw to the Continent. Roman government and way of life break down within the span of two generations, while Picts from over Hadrian's Wall and Scots from over the Irish Sea start making a nuisance of themselves. Saxon mercenaries from northern Germany get invited over in 449 by Romano-British rulers to help deal with the invaders, yet they turn on the Romano-Britons, bring all their families over and start conquering Eastern Britain, brutally ethnic-cleansing the natives. Other Germanic tribes, like the Angles (also from northern Germany), the Frisians from Holland and the Jutes from Denmark, also start coming over. The Romano-Britons try and fight back and have some successes in stalling the advance of the Continental invaders (this is where Aurelius Ambrosius and the legendary King Arthur come in), but in the end its all no good and by the early seventh century they've been hemmed into the western edges of Great Britain - Wales, Cornwall and Cumbria. Meanwhile, these Angles, Saxons and Jutes have settled down in lowland Britain (what will one day become England) and gone on to form seven kingdoms - the Angles the kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia and East Anglia; the Saxons the kingdoms of Wessex, Essex and Sussex and the Jutes the kingdom of Kent. Basically, we end up with something like this ...

However, since the 1970s, much of this has been challenged on the grounds of archaeological and genetic evidence, along with new critical approaches to the later written sources , which are now viewed by many scholars (at least as concerns their narratives up to 600) as attempts to explain the political situation of the eighth to tenth centuries and to help foster new identities (English and Welsh) through myth-making. The result is that there is very little by way of scholarly consensus.

Chris Wickham, one of the leading practitioners of early medieval history in the Anglophone world, in "The Inheritance of Rome: A History of Europe from 400 - 1000" (2009) pp 155 - 159, a magisterial survey work in the Penguin history of Europe aimed at the general public but drawing from the first rate work of Anglo-Saxon specialists like Frank Stenton, James Campbell, Barbara Yorke and Steve Bassett, still essentially presents an modified, more nuanced and less teleological version of the narrative I've just outlined above. He sees very little by way of Roman or British continuity, extensive Germanic migration and lots of fighting between Romano-Britons and Anglo-Saxons. At the same time (and this is one of the few things on which almost all historians agree now), he doesn't see widespread ethnic cleansing as having occurred - rather he argues the Anglo-Saxon invaders assimilated the conquered Romano-Britons, making them adopt their language (Old English) and Germanic paganism. And he's highly sceptical of the accounts of the formation of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms contained in the traditional narrative sources. Instead, following closely the work of historians like Steve Bassett and John Hines, he argues that the classic seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms took a very long time to form. As he sees it, lowland Britain even in the late sixth century was divided into nine and possibly many more kingdoms, each of them no bigger than the size of one or two modern English counties and roughly equivalent to the size of Roman civitates - much smaller than any of the post-Roman kingdoms on the Continent. These kingdoms themselves were built out of much smaller tribal building blocks called regiones (as they are referred to in some eighth century documents) which were on average 100 square kilometres in size - a quarter the size of the Isle of Wight, and a fortieth the size of modern day Kent. Some of these appear in a tribute list called the Tribal Hidage, produced between c.660 and c.750 for either the kings of Northumbria or the kings of Mercia, which mentions 35 tribute-paying political units in all, such as the North and South Gyrwa in Cambridgeshire or the Sweord Ora in Huntingdonshire. Units of these kind casually appear in many later documents and topographical research has revealed many more, and shall continue to do so.

On the other end of the spectrum, you have the respected landscape archaeologist Susan Oosthuizen in "The Emergence of the English" (2019) arguing for a very extreme view, that the Anglo-Saxon invasions never took place at all. Instead, she argues, marshalling lots of archaeological evidence (including her own studies of the Cambridgeshire fenlands) , that there was deep continuity with the Romano-British past. She claims that systems of common property rights and local governance, farming systems, language (she claims Brythonic and Vulgar Latin were still being widely spoken in what is now England as late as the eighth and ninth centuries) and craftsmanship all stayed the same across the period 400 - 650, and even as late as 850. She also argues, as some scholars have done, that British Christianity survived in southern and eastern England through the fifth and sixth centuries with no less vigour than before the Romans left, and that both the early Welsh and Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were based on the boundaries of Roman civitates (city territories) which in turn went back to Iron Age tribal territories. In arguing these things, she draws on the great French historian Fernand Braudel's concept of the long duree, which in his magnum opus "The Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II" (1958), he defined thus: “history whose passage is almost imperceptible, of man in relationship to his environment, a history in which

all change is slow, a history of constant repetition, ever-recurring cycles.” She also draws on the theories of socio-cultural development by modern sociologists like Pierre Bordieu. Oosthuizen does acknowledge that change happened - the people in the eastern parts of the former Roman province of Britannia came to speak a West Germanic language and identify as Angles and Saxons, while those living in the West went fully back to their Celtic roots and identified as Welsh - but argues that none of it was to do with invasions or movement of peoples from the Continent more generally. In accounting for how Eastern Britannia (what became England) came to identify with the peoples of the Germanic North Sea and speak Old English, Oosthuizen, sensibly steers clear of the fringe theory, believed by a tiny minority of eccentric linguists, that the Iron Age inhabitants of what is now Eastern and Southeast England were already speaking a West Germanic language before the Roman invasion in 43 AD. Instead she says that the mechanism is "opaque" but proceeds to draw a modern parallel: in Scandinavia and the Netherlands more than 70% of people speak good or fluent English; completely ignoring the fact that these countries have first rate state education systems with compulsory English classes from primary level and are bombarded by Anglo-American mass-media. She also takes a rather all-or-nothing view of the historiography - either you believe the Anglo-Saxon invasions took place over the course of one generation and that a complete genocide of the Romano-Britons living in Eastern England followed (which no serious scholar after Frank Stenton has argued), or you believe that the invasions didn't take place at all (a radical fringe position).

While I will admit that Oosthuizen's argument is incredibly complex and sophisticated, and as I said before I am not an expert on this period and she undoubtedly is, there are undoubtedly so many obvious problems with taking this kind of view. Put it crudely, if the Anglo-Saxon invasions never happened, how can one really explain why I'm not writing this today in some hypothetical British Romance language? Personally, I think the Anglo-Saxon invasions did happen and that, while they did not systematically replace the indigenous inhabitants, migration and settlement was substantial. As a Continental early medievalist, I am all too aware that if it was just a warrior elite coming over, Britain would have just gone the way of Frankish Gaul (what would become France), Visigothic Spain and Lombard Italy. In those places, the native Romanised populations adopted some aspects of Germanic culture (especially in relation to personal names and being buried with grave goods). They also came to ethnically identify with their conquerors as Franks, Goths or Lombards rather than as Gallo-Romans, Hispano-Romans or Italians, mainly because of the legal advantages it offered them - higher wergild (compensation given to a victim of a crime/ their family under Germanic law), freedom from taxation and the right to perform military service and speak in royal assemblies. At the same time, the Franks, Goths and Lombards had, by c.700, largely abandoned their original Germanic languages for the local Vulgar Latin dialects that then evolved into Old French, Old Spanish etc. I find the explanations of Anglo-Saxon ethnogenesis offered by Bryan Ward-Perkins in "Why did the Anglo-Saxons not become more British", English Historical Review, (2000), pp513 - 533, much more convincing, which goes very much with the grain of what the Continental parallels would suggest. For how other specialists on early medieval Britain have so far received Oosthuizen's work see the sympathetic yet critical review of Oosthuizen's book by Dr Francis Young, and the more incisive reviews by Alex Woolf and John Hines.

In between all this is a whole range of different views that I've failed to properly account for - as I said before this is far from being my specialism. I'm sure a good few of my readers know more about this than I do and if I'm getting stuff wrong, please don't hesitate to call me out on it. I can direct you to Guy Halsall's excellent (and excellently named) blog for a better overview of what we can know about what was going on in lowland Britain in the fifth and sixth centuries than I've tried to provide here - his attitude is more no-nonsense than mine, and unlike me he's a specialist in post-Roman Britain with very intimate knowledge of the sources.

The takeaway is that we really don't know what was going on in Britain in the fifth and sixth centuries - the written evidence is next to nothing; and while the archaeological evidence is quite rich, as Paul Cartledge, a leading historian of ancient Greece, memorably puts it "Spades don't lie to you, but you have to make them speak." Thus all kinds of different plausible theories as to what may and may not have happened. At the same time, every new archaeological discovery has the potential to give support to, challenge and overturn theories and open up new possibilities about what was going on in this mysterious yet formative period.

Implication number one: a sixth century tribal kingdom in the Middle Thames Valley

Now we've set up the historiographical background, you might be wondering what is the significance of the macho man of Marlow in all of this. Well, for starters, the man was buried not in a cemetery (and there are an awful lot of cemeteries from post-Roman Britain) but in a site on a hill set apart from the rest of the community. This means that, beyond reasonable doubt, he was of high social status. He's buried north-south in his orientation and facing towards the river Thames. As Dr Thomas suggests "He is deliberately positioned to look over that territory." Following from these observations, Dr Thomas argues that this macho man was probably a respected tribal leader who likely ruled over the Middle Thames Valley at some point in the sixth century. The Middle Thames Valley (Berkshire and Buckinghamshire) in this period is a region that's been very overlooked, both historically and archaeologically, in favour of the Lower Thames (what is now Greater London, Essex and Kent) and the Upper Thames (Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire). By 664, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire formed part of the disputed borderlands between the kingdoms of Wessex and Mercia, with the river Thames often serving as the border between the two kingdoms, a political set-up that would continue until the Viking invasions in the late ninth century. But would this have necessarily been the case in 564?

I think Gabor Thomas is right to draw the inferences that he does from this, which do overturn what we've previously assumed about the local area. However, this accords very well with current thinking - the views of Chris Wickham, John Hines, Steve Basset and many others that I mentioned earlier - that post-Roman Britain was an extremely politically fragmented place, uniquely so in the former Western Roman Empire, and that the formation of the seven classic Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, what historians used to call the Heptarchy (but now don't), was a long and tardy process spanning several centuries. The final third of the sixth century and the first third of the seventh have been identified as the critical period in this respect, though by 650 or even 700, the classic seven was far from being a foregone conclusion. Back in 1988, Steve Basset memorably gave a football league analogy, which goes something like this:

- Some of the smaller tribal territories mentioned in the tribal hidage, like Lindsey (Lincolnshire), Surrey and the Hwicce (modern day Gloucestershire and Worcestershire), were probably still kingdoms of their own, albeit paying tribute to Northumbria/ Mercia (whichever kingdom produced the document).

- Like the lesser, more exclusively local teams that participate in the UK FA Cup, they probably still had an outsider's chance in the late seventh century of making it into the Premier League of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (where Sussex, Essex, Kent and especially Northumbria, East Anglia, Mercia and Wessex were).

- However, by the 750s they had been completely eliminated and the FA Cup of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, was reaching its quarter finals, in which it was just the Premier League kingdoms against each other, with Essex, Sussex and Kent soon to be eliminated by Mercia.

|

| For reference here's a map of the tribal hidage I found, on David Crowther's History of England Podcast website (hides indicate the agricultural wealth of each tribe) |

Football analogies aside (and I must admit I myself am not a fan of the sport), we have no reason to presume that there wasn't an independent tribal leader operating in the Middle Thames Valley prior to 600. After all, in the tribal hidage, as you can see on the map, Berkshire features as the territory of the Noxgaga, one of the most obscure (even to specialists) of the tribute-paying tribal polities listed there, and Buckinghamshire is the territory of the Chilternsaete - a tribe that historians can't make their mind up over whether they were West Saxons, Angles or (as Chris Wickham himself briefly suggests) Romano-Britons that kept their own independent enclave going until the early seventh century. Perhaps this macho man had been one of the rulers of either the Noxgaga or the Chilternsaete. Or perhaps he was the ruler of a tribe that is completely lost to history. But either way, his existence strongly suggests that there independent tribal warlords operating in this area up until the kings of Mercia or those of Wessex finally muscled into the area in the early seventh century and eliminated the local tribes/ made them tribute-paying vassals.

We cannot be certain about his ethnicity. Grave goods, in and of themselves, cannot serve as an indication of someone's ethnic origin, as historians who've worked on the archaeological evidence from post-Roman Continental Europe, like Patrick Geary, Bonnie Effros and Guy Halsall for Merovingian Gaul, in that case determining Gallo-Romans from Franks, can confirm. I've had the pleasure of hearing Geary talk about his latest work on post-Roman ethnicity, in collaboration with paleo-geneticists, and there he reiterated the importance of not using grave goods to determine if someone was a Roman, a Goth, a Frank or whatever. At the same time, ethnic identity, like culture, in this period was very fluid, and individuals across the post-Roman West do seem to have been able to consciously change their ethnic identity. There is the possibility, for example, that this warlord, or his father or grandfather before him, might have started out as a Romano-Briton but then married the daughter of an Anglian or Saxon warlord and decided to identify with his immigrant in-laws. A similar theory exists with Cerdic (d.534), the shadowy, semi-legendary founder of the royal house of Wessex, as his name appears to be an Anglicisation of the Brythonic/ Welsh name Caradoc, and his grandson Ceawlin likewise appears to have a Welsh name, highly suggestive that Cerdic was of mixed Romano-British and Saxon ancestry.

The man was buried with bronze bowls and glass vessels, which likely came from Northern Gaul and the Rhineland (both part of the Merovingian Frankish realm), suggest that he was clearly powerful and important enough to get hold of these - a much smaller scale of the royal treasure hoards of the kings of Dumnonia and East Anglia found at Tintagel and Sutton Hoo respectively. All of this bling would have demonstrated his prestige, and he would have been able to give other luxury items as gifts to his followers to reward them for their loyal service.

The fact the man was buried with weapons is also interesting. How much actual combat this man experienced in his life, and what that in turn can suggest about the level of warfare in sixth century Britain, we cannot really say. As of yet, there is absolutely no indication that this man died in battle. Weapons are a fairly common find in burials from the fifth and sixth centuries in lowland Britain. At the Buckland cemetery near Dover in Kent, five swords, four spears and a shield boss have been found. Similarly, 25 spears and 15 shield bosses were found in the 150 Anglo-Saxon graves excavated in the giant cemetery at Overstone in Northamptonshire, discovered in 2019. To give just one more example, at an Anglo-Saxon cemetery excavated at Morden Road in Mitcham, part of the borough of Merton in South London),between its discovery in 1888 and the 1920s, one fifth of the 230 burials dating to the period c.450 - 600 there contained weapons, with a total of twelve swords being found there.

|

| Sword and shield boss from Merton cemetery |

Does this mean that warfare was endemic in post-Roman Britain and that the average adult male living in the period c.450 - 600 was likely to experience armed combat? That's highly debatable. Some historians and archaeologists, especially those who, like Oosthuizen, are sceptical of the Anglo-Saxon invasions having happened at all, claim that there's very little evidence for large-scale or endemic warfare in this period. They claim this on the grounds that there is no archaeological evidence for battles and sieges having taken place in this period, and that the individuals whose graves contain weapons were buried so for symbolic reasons. Yet the truth is, if we had to go on archaeological evidence alone, we wouldn't be able to prove that most medieval wars happened. Beyond a few famous cases, like Visby in Gotland (1361) or Towton in Yorkshire (1461), medieval battlefield archaeology is rather underdeveloped. And, at a certain level, claiming that burial with weapons was largely symbolic misses a point. What was that symbolism anyway, and why was it important? This brings us to ...Implication number two: one of the most important transformations in British and European gender history

The answer to the question presented earlier is that the weapons would have been symbolic of the deceased men's manhood, their status as free men and, in the case of the macho man buried at Marlow, his status as an elite free man. Thus, arguably, the actual levels of warfare in sixth century Britain are neither here or there and basically irrelevant. What really mattered is that it was important for free men, and elite men in particular, to identify themselves as arms-bearing men, fighting men - in a word, warriors. This was a phenomenon by no means unique to Britain. It was to be found everywhere across the former Western Roman Empire, from the Rhine frontier and Noricum (roughly modern day Austria) to Africa (roughly modern day Tunisia) and Mauretania (modern day northern Algeria and Morocco). All across the former Western Roman Empire in the fifth and sixth centuries, erstwhile provincial societies became militarised and dominated by warrior elites.

That Western Europe should, by 600, end up dominated by male warrior elites, is arguably, in the grand span of the history of human civilisation, unremarkable. Most societies across the globe from the Bronze Age through to early modernity were dominated by some kind of militarised male elites - Homeric Greek kings, Iron Age European tribal leaders, the kshatriya caste of ancient Hindu India, the mamluk dynasties of the medieval Islamic world, Mongol khans, the samurai of Feudal Japan, Aztec jaguar warriors, Zulu chieftains, Sioux braves, I could go on.

Yet in the history of Britain and Western Europe this is so significant for two reasons. The first is the long-term significance of what happened in the fifth and sixth centuries. Western Europe would remain dominated by a militarised (male) ruling class for the rest of the Middle Ages and even a little bit beyond (if we take 1500 for the end of the medieval period, as is conventional). This should not be news to anyone . The knight, an aristocratic warrior clad from head to foot in shining armour, armed with sword and lance and riding atop a splendid warhorse and subscribed to the elite code of chivalry, is one of the most iconic symbols of the European middle ages in the popular imagination. And in the UK, warrior kings like William the Conqueror, Richard the Lionheart, Edward I, Robert the Bruce and Henry V feature pretty large in how most people remember their medieval history. While obviously the nature of the warrior elite changed profoundly over the course of roughly a millennium, the basic concept proved incredibly durable. While its debatable whether the gentry of Elizabethan and Jacobean England were still warriors in any meaningful sense, and some historians like Mervyn James would argue yes, they seem to have continued to see themselves that way.

|

A splendid English Renaissance alabaster tomb sculpture of Sir Henry Neville (1564 - 1615), lord of the manor of Billingbear, at St Lawrence's Church, Waltham St Lawrence, Berkshire, just 9.8 miles south of where our friend, the sixth century macho man of Marlow, was found. The fact he's decked out in a full suit of Greenwich plate armour tells us everything we need to know about his wealth, status and, most importantly for us, self-image.

|

|

A facsimile of the tomb monument of William Penne (1567 - 1639) depicting him in full armour with his wife Martha to his right and his son John (also in armour) and daughter Sibyl and Katharine below them, at Holy Trinity Church, Penn, Buckinghamshire, just 7 miles to the northeast of where our friend the Marlow macho man was found. The fact that William Penne himself actually spurned his one opportunity to do military service, ignoring the summons to the county militia in 1631 when the threat of foreign invasion loomed (in protest of Charles I's unconstitutional policies), shows that the way Penne wanted to have the engraver depict him had everything to do with his social status and self-image and nothing to do with what he actually did in life.

|

The second is where this stands in relation to what came before. So far I've been implying that a transformation in the nature of the male elite took place across the Western Roman Empire in the fifth and sixth centuries, but from what kind of elite? The answer is that the ruling class of the later Roman Empire was, first and foremost, a civilian one, consisting of two main components. On the one hand, there was the old senatorial aristocracy, politically marginalised at the imperial court for the most part yet still carrying much clout in Rome and many of the provinces. On the other hand, there was a class of elite provincial civil servants, who were also very rich landowners and enjoyed extensive patronage and close ties with the imperial court, that had risen with the administrative reforms of Diocletian (r.284 - 306) and Constantine the Great (r.306 - 337) after the Imperial Crisis of the Third Century (235 - 284). The army was almost completely separate from them, ever since an edict of Emperor Gallienus (r.260 - 268) banned members of the senatorial class from serving as military commanders and occupied a somewhat subordinate position socially, if not quite so politically. Army commanders tended to be from lower class provincials or of barbarian origin, and soldiers were widely despised/ regarded as inferior by civilian elites. The one big exception to this was the emperor, who tended to come to power through the army, who continued to make and unmake emperors every now and then like they did all the time in the third century, and thus in the later Roman Empire we get a lot of emperors from quite humble backgrounds. Diocletian himself was the son of a former slave from Illyria (modern day Croatia), for instance, and the East Roman emperors Justin (r.518 - 527) and Justinian the Great (r.527 - 565) were from a peasant family in Moesia (modern day Serbia).Now, in patriarchal societies, as the later Roman Empire (and post-Roman Britain and every society I've mentioned in this post) undoubtedly was, a male elite needs to be able to boss around two different groups - women and lower status men. In order to do this, they need to be able to demonstrate that men are superior to women and that some men are superior to others. This is where masculinity come in - the idea that masculinity, however defined, is preferable to femininity justifies dominance over women, while the idea that certain kinds of masculinity that are attainable by only a small elite of men are better and purer than others, justifies dominance over other men, defined as lesser or inferior. Thus through notions of masculinity, elite men can justify bossing around men of other ranks, social statuses, classes, castes, vocations, ethnicities, races, religions etc or at different stages in the lifecycle to them (its all about intersectionality, innit!)

The kind of masculinity the Roman civilian aristocracy embraced was one based on many different components. One was their educations attained either in the public secondary schools that could be found in most major provincial towns or with a private tutor. This equipped them to be able to write poems in Latin hexameters like Virgil or Horace as well as being able to recite whole verses of the Aeneid or the Odes from memory, and deliver lengthy, eloquent and persuasive speeches like Cicero, amongst other things. Such an education served as the perfect marker of elite status that would at once demonstrate intellectual superiority and membership of an exclusive social club - being able to speak perfect first century BC high literary Latin would be the equivalent of speaking in Shakespearean English verse today, not that anyone really does. It was also what enabled new people to be recruited into the elite i.e. St Augustine (354 - 431) and Libanius (313 - 393) both came from lower middling provincial (African and Syrian respectively) backgrounds, but were able to rise high in the imperial civil service and gain favour at the imperial court because of their eloquence and literary talents. Another component was their leisured lifestyle - not having to work with their hands or fight against the barbarians on the frontiers, instead being able to chill-out for lengthy parts of the year in their plush country villas with beautiful gardens and mosaics, and enjoy all the good things in life while devoting as much of their leisure time (otium) to high-minded masculine pursuits like writing poems and letters, studying and philosophical contemplation. Yet another component was their masculine self-control (rooted in ancient Greek humoral theory and stoicism) in which they maintained the unique heat that men had from their foetuses being cooked for longer in the womb by avoiding excessive physical toil, eating, drinking and sex, in contrast to women and lower status men who were colder, wetter and more driven by their base appetites, and therefore were unfit to be in charge. The final component was holding public office, either in the imperial civil service, local magistracies or municipal assemblies, and participating in the civil life, by sponsoring the construction of public works and providing bread and circuses through their aristocratic largesse (generosity) for the plebs.

|

Quintus Aurelius Symmachus (345 - 402), a late Roman senatorial aristocrat, man of letters and outspoken pagan who served successively as governor of Africa (373), urban prefect of Rome (384 - 385) and consul (391), depicted here, in an ivory diptych, being brought up to the Sun god Sol Invictus by two winged genii. Symmachus was the quintessential Roman civilian aristocrat. He was fabulously wealthy, possessing twelve villas and extensive estates in Italy, Sicily and Mauretania. He devoted most of his free time to literary pursuits (he counted the poet and rhetorician Ausonius as one of his best friends) and produced an extensive letter collection that survives to this day. In one letter, Symmachus reveals that he organised some gladiatorial games, for which he managed to procure lions, crocodiles and bears, and got 29 Saxon prisoners of war to fight as gladiators - however, the Saxons opted to strangle themselves in their prison cell the night before the games could commence. He also famously got into a bit of a scrap with St Ambrose, bishop of Milan, over whether the altar of Victory should be restored the senate house after Emperor Gratian removed it in 382 - Symmachus did not succeed.

|

Did this kind of elite exist in Roman-Britain? Unlike Gaul or Spain, Roman Britain doesn't seem to have had any senators, or produced any authors we know by name. This kind of goes with the grain of the traditional view that Romanisation in Britain only went skin-deep (see BBC In Our Time episode on Roman Britain for a very good discussion of this). In some regions, such as what would become Wales, Cornwall and the North of England, this does appear to have been true, and Roman rule was indeed mostly a military occupation, with the traditional Iron Age social structures being left intact. But the scholarship of the last fifty years has demonstrated that the lowland areas of Britannia (what is now Southern England, East Anglia and the Midlands), had become thoroughly Roman in terms of economy, social structure and culture by the fourth century AD. This is borne out by the archaeological record. Most important of all, is the hundreds of Roman villas that have been excavated since the 1810s - Wikipedia lists about 469 (I really did count them all) as being confirmed to exist, each with links to the summaries of their excavations on the Historic England Database, though the list is probably far from comprehensive. Gloucestershire, home to Cotswolds and the source of the Thames, has by far the greatest concentration of Roman villa sites - 52 in all, including two of the grandest - Chedworth and Great Witcombe, both of which you can visit. The Middle Thames Valley seems to have had its fair share of Roman villas, including 2 at Hambleden (5.5 miles to the west of where our friend the macho man rests), 1 at High Wycombe (4.7 miles to the north), one at Cox Green (7 miles to the south) and one at Maidenhead (4 miles to the southeast). Besides a few exceptions, such as Fishbourne in West Sussex (anyone who did the Cambridge Latin Course Book 2 will remember this one), absolutely none of the occupants of these villas are known to us by name. What we can know is that their inhabitants were very wealthy - luxurious mosaics, underfloor heating, bathhouses and coin-hoards are very common finds - and had similar cultural tastes to the elites in Gaul, Spain and elsewhere. At least some of them seem to have been, by the mid-fourth century, Christians, as reflected by the remains of a household church along with frescoes and mosaics depicting Christian symbols and themes discovered at Lullingstone. And even if Roman Britain didn't produce any notable writers, some of the inhabitants of these villas had definitely received extensive educations in Classical literature. For example, a mosaic in the dining-hall (triclinium) depicting Zeus behaving badly in typical Zeus-fashion, has a Latin couplet above it which translates to "If jealous Juno had seen the bull swimming she would have gone with greater justice to the halls of Aeolus." The patron, whoever he was, really is showing off his knowledge of Latin literature by playing a complex game here - the couplet alludes to Book One of Virgil's Aeneid, where Juno tries to get Aeolus to drown Aeneas, but its been transferred here to the Rape of Europa, recounted in Ovid's Metamorphoses. And it wasn't just Augustan era Latin literature that the elites of Roman Britain were familiar with. Probably the most exciting archaeological excavation of last year was the discovery of a Roman villa in Rutland with a mosaic from the third or fourth century depicting the fight between Achilles and Hector in the Iliad - a clear indication that some of the elites in Roman Britain could read Greek too. |

| A surviving fresco from Lullingstone (now in the British Museum) depicts the Chi-Ro (the first two capital letters of the Greek proper noun Christos, adopted as a symbol by the Emperor Constantine after the battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312) with the Alpha and Omega from the Book of Revelation 22:13. |

|

| Another fresco from Lullingstone appears to depict worshippers with their hands raised in prayer. Late Roman frescoes in this style are unknown outside of the Synagogue at Dura-Europos in Syria. |

|

| The mosaic (dated to c.360 AD) depicting the Rape of Europa |

|

| An artistic reconstruction of what the Roman villa at Lullingstone would have looked like c.360 AD by Allan Sorrell |

|

| The Rutland mosaic of Achilles and Hector |

|

| An aerial shot by English Heritage of the remains of the Roman villa at Great Witcombe looking west |

So, in sum, Roman Britain's elites were much like the civilian aristocrats everywhere else in the Roman Empire. What happened to them, and how do we get from them to our sixth century macho man? Just like the immediate post-Roman period in Britain (450 - 600) is so mysterious, as discussed earlier, when and why Roman rule ended in Britain remains controversial among scholars. Above all, the question that divides them, is thus: did Roman imperial rule end in Britain because the central authorities could longer afford to keep it within the Empire any more due to civil wars and barbarian invasion going on on the Continent? Or did the Romano-Britons themselves choose to break away from the Roman Empire out of serious dissatisfaction with imperial government - in other words, was this a Brexit before Brexit? Some Marxist historians, such as E.A Thompson and Neil Faulkner, have even speculated, on the flimsiest evidence, that a peasant's revolt brought about the end of Roman rule in Britain. But what seems to be fairly clear is that between 383 and c.450, not only did Roman imperial government disappear from Britain, but so did almost all the distinctively Roman features of the Romano-British way of life. The majority of the Roman villas, including all the ones I've mentioned, were abandoned in this period. The ones in the Middle Thames Valley seem to have been abandoned around 400 AD i.e. at the Hambleden one, the last coin to appear there was one of Arcadius (383 - 408). Some were abandoned quite late, after any Roman troops or imperial administrators were likely to have still been present - for example, a new mosaic was created at Chedworth in 423, a sign that it likely carried on business as usual into the second quarter of the fifth century, and its unclear when in the first half of the fifth century the villas at Lullingstone and Great Witcombe were abandoned. But by 450 at the latest, none of the Roman villas in Britain were still in habitation, and their sites were starting to be quarried for building materials - something that was still going on as late as eleventh century, as reflected by recycled Roman bricks turning up in Anglo-Saxon churches. Major cities, including the capital Londinium, were abandoned by this point as well. Coins appear to have stopped being imported to Britain in large quantities after 402. And wheel-turned pottery and glassware stopped being manufactured in Britain by c.450. All of this points to a thoroughgoing political, economic and social crisis over the span of 2 - 3 generations.

Unlike on the Continent, where we have abundant writings from the old Roman civilian aristocracy throughout the fifth and sixth centuries, from men like Sidonius Apollinaris (c.430 - 489), Cassiodorus (c.490 - 583) and Gregory of Tours (535 - 594), we can really only guess the fate of the Romanised elites in Britain. The villa abandonment described earlier should be something of an indication. Examples like Chedworth, not abandoned until sometime after 423, show that the Romano-British civilian aristocracy weren't all killed off in the wake of the rebellions of Magnus Maximus in 383 and Constantine III in 407, generals based in Britain who attempted to usurp the imperial throne, or by bloody-minded peasants. At least some, and for all we know the majority, of the personnel of the Romano-British civilian aristocracy survived and didn't flee to the Continent. But the effect of what went on in the first half of the fifth century was that most of what underpinned their power had disappeared and much of their culture seemed pretty redundant.. Above all, without the Roman legions, Romano-British communities needed some way to defend themselves.

Its in these circumstances that, I suspect, many erstwhile civilian aristocrats would have become warlords and established armed followings, thus solving their communities needs for military defence while creating around that new social and political bonds based around tribal loyalty and obligation. And of course, Continental migrants/ invaders with their own warrior elites were coming over as well. In these circumstances knowledge of Classical literature and taste in mosaics and fine wine was not going to get you very far, but being big, strong and athletic, having good quality weapons and military equipment and being proficient at cutting flesh, breaking bones and puncturing internal organs, all of these being qualities our friend the macho man had in spades, could help you qualify for leadership of a tribal community, whether Romano-British, Anglo-Saxon or mixed in its members. For much more concise and better general explanations at how male elites move from cultural to military dominance or the other way, and the limitations of both, see this post from Dr Rachel Stone's excellent blog - I owe a fair amount of intellectual debt to her, especially in the present blogpost.

At this point, I've done my best to both locate the Marlow macho man in his proper context and draw out what implications I can and this post has probably exceeded any reasonable length. I'll wrap up with one final observation. Its interesting to note that so many of the key texts in helping define and shape late medieval aristocratic culture and masculinity looked back to the time of the Marlow macho man, be they the Old English poem Beowulf (written sometime between 604 and c.1000) or the Arthurian romances of the twelfth to fifteenth centuries. Of course these were heavily fictionalised depictions of the sixth century, and may have projected the values of the present age back on to the past (certainly with regard to the Arthurian romances).Perhaps it would be too ludicrous to suggest that some kind of residual folk memory of this period as formative in the creation of the warrior elites of what would become England and Wales led the poets to choose sixth century settings, or perhaps not. Yet, nonetheless, bringing them in here is helpful nonetheless, because it helps us think about change and continuity in the warrior elites of medieval Britain - how much had stayed the same between the Marlow macho man Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur.

I should also announce here that, since I am terrible at observing anniversaries, this blog has been up on the web for more than six months. Thank you to everyone for reading my posts and providing support and encouragement - you help keep me motivated in this.