Happy Valentine’s Day everyone. Now I’m not going to write a

post about the history of Valentine’s Day itself, though I’d like to say that yes

it does have a medieval history but later than the kind of medieval I write

about here. A lot of very significant historical events happened on this day: the

Abbasid Revolution in Iraq in 748, the Papal Schism of 1130, the coronation of

Akbar as the ruler of the Mughal Empire in 1556, Captain Cook being killed by

Natives in Hawaii in 1779, Ruhollah Khomeini issuing a Fatwa against Salman

Rushdie in 1989 and the launching of YouTube in 2005, to name just six. But of

course, this blog bearing the name that it does, we’re going to be focusing on

an event in Carolingian history that happened on 14th February, in

the year 842 no less.

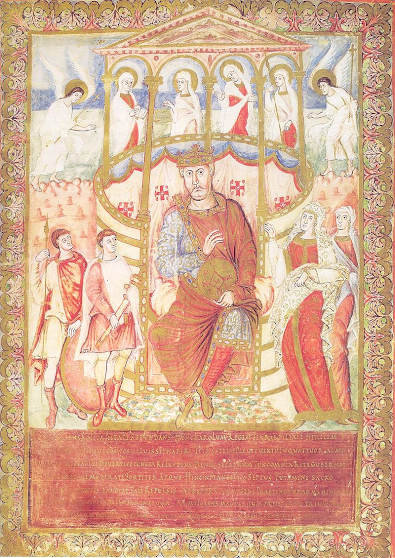

Ninth Century Frankish cavalry in the Golden Psalter of St Gall, nicely sets the tone for this

842 of course was in the middle of the Carolingian civil war

of 840 – 843, between the three sons of Emperor Louis the Pious. I’ve talked

about this a fair few times before, but at the root of it were the same forces that

meant that ninth century Carolingians could not have nice things – the failure

to equitably share power among the dynasty’s members, aristocratic factionalism

at court and opportunistic foreign powers (above all, the Vikings) deciding to get

involved. Lothar was trying to hold the empire together with his nephew Pippin

of Aquitaine, while his younger brothers Louis and Charles thought they deserved

their own piece of the pie.

By this point, it seemed like the civil war wasn’t going

great for Lothar, as in June 841 he and Pippin had suffered a catastrophic

defeat at Fontenoy. The next 8 months of the civil war saw very little actual

fighting. Instead, the rival Carolingian kings sent envoys between each other,

trying to negotiate a peace. They try and win over supporters from amongst the

Frankish nobles who were either trying to stay neutral, or were on the opposing

side. Meanwhile, opposing armies marched around the countryside of Northern France

and the Benelux countries, garrisoning citadels here, forcing enemy strongholds

to surrender there, blocking off routes where the enemy might approach

elsewhere, and so on. Contrary to what some people might think, battles weren’t

all important in ninth century warfare and were often indecisive. Indeed, its

revealing how our sources tell us so much about the campaigning side of

Carolingian warfare, yet provide us with barely any description of how the

battles were fought, instead focusing on their aftermath and consequences.

And there are a lot of sources for this section of

Carolingian history. Indeed, the 35-year period 828 to 863 is quite possibly

the best documented generation in Western political history between the fall of

the Roman Republic (66 – 31 BC let’s say) and the age of Richard the Lionheart,

John Lackland, Philip Augustus and Pope Innocent III (1188 – 1223). We know so

much about the intricacies of Carolingian politics at this time, and the full

range of partisan perspectives.

One of these sources is the historian Nithard (795 – 844).

Nithard is a very interesting chap, indeed quite a remarkable one. He was the illegitimate

son of Bertha, the third daughter of Charlemagne, and the court poet Angilbert.

I don’t want to go too much into this now, but Charlemagne seems to have

allowed his daughters an unusual degree of sexual freedom, which their brother

Louis the Pious thoroughly disapproved of. The emperor’s sisters were among the

first to be targeted in his attempt to “drain the swamp” at Aachen. Nithard

seems to have been educated at Charlemagne’s palace school at Aachen and thus

was thoroughly literate, proficient in the Latin language and very knowledgeable

of the ancient Roman Classics, especially the works of the historian Sallust

and the poet Lucan (both of whom wrote about civil war). He had of course also

learned how to ride, hunt, fight with weapons and conduct himself around court.

Indeed, one might say his education was fairly typical of a high-ranking

Carolingian aristocrat. Before the civil war, Nithard had been a courtier,

soldier and lay abbot of Saint Riquier.

Thus Nithard’s Histories provide us, along with the

works of Einhard, Angilbert, Eberhard of Friuli and Dhuoda, with valuable

insights into the attitudes of lay aristocrats in the Carolingian Empire and how

they saw the workings of politics. Nithard wrote his history as the events themselves

unfolded, and like Xenophon, Julius Caesar and Ammianus Marcellinus before him,

he wrote as a soldier and politician with first hand experience of it all. Of

course, as your average 16-year-old in a GCSE exam might say, crudely, that means

he’s “biased” – Nithard fought for Charles the Bald and portrays his king in a

positive light, and the enemy Lothar in a very negative one. Above all, he saw

the civil war as a tragedy tearing the Carolingian state (res publica in

the original Latin) apart and highly damaging to the welfare of the Frankish people,

yet kept faith that everything that unfolded was God’s judgement. Let us see

what he has to say about what went down on 14th February 842.

On the fourteenth of February Louis and Charles met in

the city which was once called Argentaria but is now commonly called

Strasbourg. There they swore the oaths recorded below; Louis in the Romance

language and Charles in the German. Before the oath one addressed the assembled

people in German and the other in Romance. Louis being the elder, spoke first …

The basic sum of what Charles and Louis says next is thus: Lothar

is an absolute rotter, and the civil war is all his fault. We’ve tried to offer

peace on the most reasonable terms, yet he refuses. But at least us two look

out for each other as siblings, so we’re going to swear these oaths to show you

what good loyal bros we are, and that we’ll work together to heal the body politic.

Nithard then records the oath Louis swore in front of

Charles the Bald’s soldiers in Romance thus:

Pro Deo amur et pro Christian poblo et nostro commun

salvament, d’ist di in avant, in quant Deus savir et podir me dunat, si

salvarai eo cist meon fradre Karlo et in aiudha et in cadhuna cosa, si cum om

per dreit son fradra salva dift, in o quid il mi atresi fazet et ab Ludher nul

plaid numquam prindrai, qui, meon vol, cist meon fradre Karle in damno sit.

The English translation goes thus:

For the love of God and our Christian people’s salvation

and our own, from this day on, as far as God grants knowledge and power to me,

I shall treat my brother with regard to aid and everything else a man should

rightfully treat his brother, on condition that he do the same to me. And I

shall not enter into any dealings with Lothar which might with my consent

injure this my brother Charles.

Charles then swore the same oath to Louis’ troops in Old High

German:

In Godes minna ind in thes christianes folches ind unser

bedhero gehaltnissi, fon thesemo dage frammordes, fram so mir Got geuuizci indi

mahd furgibit, so haldih thesan minan bruodher, soso man mit rehtu sinan bruher

scal, in thiu thaz er mig so sama duo, indi mit Ludheren in nohheiniu thing ne

gegango, the minan, uuillon, imo ce scadhen uuerdhen.

Then Charles’ soldiers swore this oath in their own Romance language:

Si Lodhuuigs sagrament que son fradre Karlo jurat

conservat et Karlus, meos sendra, de suo part non l’ostantit, si returnar non l’int

pois, ne io ne neuls cui eo returnar int pois, nulla aiudha contra Lodhuuuig

nun li iu er.

Which in English is:

If Louis swore the oath which he swore to his brother

Charles, and my Lord Charles does not keep it on his part, and if I am unable

to restrain him, I shall not give him any aid against Louis nor will anyone

whom I can keep from doing so.

Louis’ troops then did so in their own language:

Oba Karl then eid then er sinemo bruodher Ludhuuuige

gesuor geleistit, indi Ludhuuuig, min herro, then er imo gesuor forbrihchit, ob

ih inan es iruuenden ne mag, noh ih noh thero nonhhein, then ih es irruenden

mag, uuidhar Karle imo ce follusti ne uuirdhit.

In English:

If Charles swore the oath which he swore to his brother Louis,

and my Lord Louis does not keep it on his part, and if I am unable to restrain

him, I shall not give him any aid against Charles nor will anyone whom I can

keep from doing so.

The oaths as they appear in Nithard's histories

Besides political significance, what makes the oaths so

interesting is from the standpoint of written language. Here we are dealing

with some of the very earliest examples of written Continental European

vernaculars. In the case of what Nithard calls the “Roman” or “Romance”

language, which is very clearly Old French, the Oaths of Strasbourg as recorded

by Nithard are the very first text ever to have been written in that or any

other Romance language. In the case of Old High German, a few texts had been

written earlier in the Carolingian period, such as the Latin-Old High German

glossary called the Abrogans (c.770), or the Merseburg Charms (the

only surviving pre-Christian Germanic religious text). The oaths thus offer us lots

of insight into what these languages were like at this point in time, and how

they would later evolve.

As I’m not a philologist, I’ll keep the discussion of linguistics

brief. For the Old French you can very clearly see the languages’ Latin roots.

Some words are still in their Latin forms i.e. Deus (God), jurat (he

swore – historic present), conservat (he keeps), numquam (never)

and nulla (not any). But there’s clearly a lot of evolution i.e., amor

(love) in Latin has moved closer to the French amour with amur; avant

is recognisably the French word for before, as opposed to the Latin ante; and

sendra, soon to evolve into the Modern French seigneur (lord). auxilia

has evolved into aiudha, which is actually closer in spelling and

pronounciation to the Spanish than the French word for help; likewise, podir,

which has evolved from the Latin potere is cloiser to the Spanish poder

than the French pouvoir. The verb tenses also appear to be closer to

French i.e., for the conditional/ future words like salvarai and prindrai

have endings recognisably like how they would be in Modern French.

For the Old High German, I really can’t claim much expertise

– one term in year 7 is the only time I’ve ever formally studied any German, which

I know is problematic given how much important Carolingianist scholarship is written

in German. Still, you can see recognisable forms of German words in this text

i.e., folches (clearly related to volk – people), bruodher

(clearly related to bruder – brother), herro (clearly related to herr

– lord or master), dage (clearly related to tag – day) and Got

(God). And uuillon is clearly related to willa in Old English and

will in modern German and English.

Thus, the Oaths of Strasbourg are a moment of huge

historical significance in the history of Western European languages. Indeed,

from the Romance side of things, it basically marks the terminus ante quem

for when the Vulgar Latin dialects spoken in Gaul evolved into Old French –

when exactly one became the other is highly debated, but it was certainly before

842. Other Romance languages appear fully in written documents slightly later –

Italian is the next to come, in the 960s, followed by Spanish and Portuguese;

Romanian is the last, first appearing in 1521 (in Cyrillic letters, no less).

What was the attitude of the Carolingians to vernacular

languages. Well, its safe to say that in order to successfully navigate high

society in the ninth century Carolingian Empire, you had to be trilingual. Louis

the Pious had his sons Lothar, Pippin, Louis and Charles educated in Latin, Old

French and Old High German, of which the Oaths of Strasbourg are themselves

evidence, and pretty much all of the high nobility (the reiksaristokratie)

would have been educated the same, especially since many of them like Eberhard

of Friuli owned lots of estates in both Romance and Germanic speaking areas.

How much bilingualism, let alone trilingualism, spread down the social

hierarchy is much less certain. Charles and Louis’ soldiers, who we can

reasonably assume to have been drawn from amongst the middling landowners and

well-to-do free peasants, could only speak their native vernaculars, and so

said their oaths in them, unlike Charles and Louis who said their oaths in German

and Old French respectively so the other side’s troops would understand. At the

Council of Tours in 813, Charlemagne decreed that priests, depending on where

they were, should preach either in the Lingua Romana (Old French) or Theodisc

(Old High German) so the common folk could understand.

A ninetenth century artist imagines the scene of the Oaths of Strasbourg

As written vernaculars go, we have only one other example of

written Old French from the Carolingian era, a short late-ninth century poem on

the martyrdom of Saint Eulalia. After that, the next examples of written Old

French appear in the twelfth century with the birth of the chansons de geste

and other early chivalric fiction. For Old High German, there’s quite a bit

more from the Carolingian period. For example, the monk Otfrid of Wissembourg

(a monastery now in Alsace, France) produced the Evangelienbuch, an Old

High German verse translation of the Gospels, for King Louis of East Francia.

There are also some poems like Muspilli (a poem about Hell), the Hildebrandslied

(a fragmentary epic), the Georgslied (about St George) and the Ludwigslied

(about a Frankish victory over the Vikings). Still, the amount of Old High

German literature that survives pales in comparison to the amount of Old English

literature surviving from 685 to c.1100. Yet when you factor in the surviving

Latin literature, far more poems, treatises and histories survive from Carolingian

Francia in the ninth century than from the whole Anglo-Saxon period. Its

because they’ve got an unusually high proportion of vernacular texts, that

Anglo-Saxonists (or as some would now prefer to be called, Early MedievalEnglishists) are able to justify obsessively fixating on so few texts, to thepoint that Beowulf and the Battle of Maldon have been sucked dry and done todeath. Meanwhile, a great deal of medieval Germanist scholarship focuses on reconstructinghypothetical texts that may have never existed, rather than the Old High German

texts that are actually there. The Carolingians, however, had different priorities

to us and preferred Latin literature by far.