Meet Guibert de Nogent (1053 – 1125), the abbot of a

monastery in Picardy, northern France. Guibert’s seventy years of life

coincided with some pretty tumultuous and exciting events – the Norman Conquest

of England, the ideological struggle between the German emperors and the popes

that is somewhat misleadingly called the Investiture Controversy (the right to invest

bishops was part of it, but far from the whole story), the First Crusade, the

explosion of new monastic movements like the Carthusians and Cistercians, a

campaign across the whole of Catholic Christendom to reform clerical morality

and the emergence of urban self-government in the West for the first time since

classical antiquity.

|

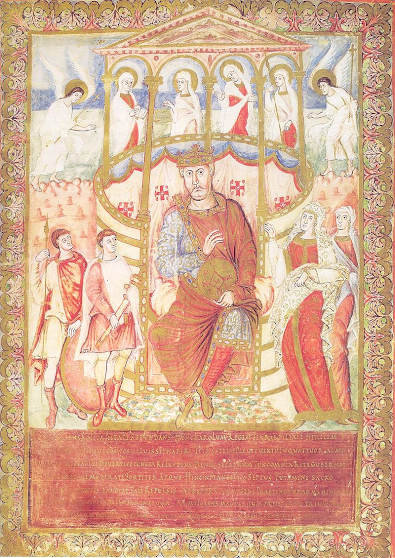

| A self-portrait of Guibert de Nogent from his Tropologies of the Prophets shows Guibert (in his black Benedictine robes) offering his book up to Christ enthroned, Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Lat 2502, folio 1 |

Guibert had opinions

on all of these things going on in the world, despite never leaving his corner

of northeast-France save for one brief trip to Burgundy, as is attested in his

writings, even if some of them are written from a quite parochial angle. He

wrote a treatise on saints and relics, a history of the First Crusade called The

Deeds of God through the Franks and an autobiography called the Monodies,

which includes within it a history of his abbey of Nogent-sous-Coucy and an

account of the bloody uprising of the citizens of Laon against their bishop in

1112 which resulted in a short-lived urban republic called the Laon commune.

Guibert is quite a household name among crusades historians, but arguably he’s

most significant as the author of the Monodies, written between 1108 and

1115. Guibert called them the Monodies (Latin: Monodiae) because

that term meant a song sung by one person. As Isidore of Seville (560 – 636)

explained in his early seventh century encyclopaedia Etymologies:

Original Latin: Cum autem unus canit, Graece monodia, Latine

sincinnium dicitur; cum vero duo canunt, bicinium appellatur: cum multi,

chorus.

My translation: When one person sings, while in Greek it is

said to be a monodia, in Latin it is said to be a sincinnium; indeed,

when two people sing, they call it bicinium, and when many people sing,

they call it a chorus.

The Monodies were the first complete autobiography to

have been written in the West since St Augustine of Hippo’s Confessions (c.400).

Indeed, it is the shadow of St Augustine that lurks behind Guibert de Nogent’s

work. Like St Augustine, who was hugely influential, Guibert believed that the

human mind and soul were locked in a constant struggle against their own pride

and the various corrupting forces present in the material world and this is the

central theme that runs throughout his autobiography. He also believed that

demons could assist in leading humans down the path of pride, temptation and

corruption, and this will essentially be the focus of this series. And like

Augustine in the Confessions, Guibert’s story is that of a boy who

starts out with promise, goes down the path of sin in adolescence but later

relents thanks to God’s boundless compassion and patience – indeed, both

deliberately echo the story of the Prodigal Son in the Gospel of Luke.

|

| St Augustine of Hippo (354 - 431): Guibert de Nogent's personal hero and inspiration |

One could also say that Guibert was to some degree writing

in an established genre of religious writing, one which revolved around using

“experiences (experimenta)” as “examples (exempla)” to teach good

or bad morals. Many monks had written works in this vein, which could get quite

intimate and personal, such as Otloh of St Emmeram (1010 – 1072) in his letter

to his friend, William of Hirsau. Indeed, beyond Guibert’s youth, his

autobiography essentially reads like a collection of anecdotes with moral

lessons, in many of which Guibert himself is just a side-character.

Nonetheless, while this is a carefully curated

autobiography, Guibert de Nogent as a teenager had been taught by Anslem of

Bec, the great theologian and future archbishop of Canterbury, and had fully

internalised his trademark saying “If I look within myself, I cannot bear

myself; if I do not look within myself, I do not know myself.” Also, if this

was all just a moralistic exercise, or a story of faith and devotion to God

being tested, why did Guibert focus on himself? Surely, he could have just

focused on Bible stories for his experimenta, as Otloh had done, or the

lives of the saints in providing instruction on how to live a good life and

avoid evil, as these were more than sufficient for that purpose. There’s little

doubt that Guibert saw himself as a unique somebody with distinctly personal

challenges to overcome as well as ones that spoke to the experiences of your

regular medieval monk. But note that he did not see himself as a unique

somebody in a positive, celebratory way. This was a man who never learned to be

happy with himself, and while a moderate amount of self-deprecation was de

rigueur for a medieval monk or cleric (there’s plenty of that in the writings

of Guibert’s mentor, St Anselm of Canterbury) Guibert takes it to excessive

levels in the Monodies. Yet despite his crippling insecurities and

anxieties was able to accomplish all that could have been expected of him and

more in life and was not driven to depression and suicide.

Now, to get a sense of the general tone of the text, lets

see first how Guibert begins his autobiography:

I confess to your majesty, O God, the innumerable times I

have strayed from your paths, and the innumerable times you inspired me to

return to you. I confess the iniquity of my childhood and my youth, still

boiling within me as an adult. I confess my deep-seated penchant for depravity,

which has not ceased in spite of my declining strength. Lord, every time I

recall my persistence in self-defilement and remember how you have always given

me the means of regretting it, I can only marvel at your infinite patience. It

truly defies the imagination. If repentance and the urge to pray never occur

without the outpouring of your spirit, how do you manage to fill the hearts of

sinners so liberally and grant so many graces to those who have turned from you

and who even provoked you?

Now, in a sense, Guibert is following St Augustine’s Confessions,

by giving a meditation on the nature of God and his relationships with humans. His

theological training from St Anselm of Canterbury is also much in evidence here

– two of St Anselm’s great specialisms were in ontology (the study of the

nature of God as a cosmic being) and moral theology or, in GCSE RS/ A Level

Philosophy terms, “the problem of evil” (why does God allow bad things to

happen in the natural world and humans to sin). But even if a lot of the

language, very eloquent nonetheless, is quite generic, Guibert unlike Augustine

in the first five chapters of the Confessions, makes it explicit that this isn’t

about God and man generally, its about God and him. Right from the start,

Guibert is making it clear that this is about him as a unique somebody, and a

uniquely wretched and sinful somebody, who God with his infinite power and

goodness somehow manages to redeem. To while Guibert is undoubtedly taking his

lead from one of the greatest of the Church Fathers of ancient Christianity,

and one of the most prominent Catholic theologians of his own day, he is from

the start writing something original.

Later on in the first chapter, Guibert says:

O good God, when I come back to you after my binges of

inner drunkenness, I don’t turn back from knowledge of myself, even though I

don’t otherwise make any progress either. If I am blind in knowing myself, how could

I possibly have any spark of knowledge for you? If, as Jeremiah says, “I am the

man who has seen affliction” [Lamentations 3:1], it follows that I must look

very carefully for the things that compensate for that poverty. To put that

differently, if I don’t know what is good, how am I to know what is bad, let

alone hateful? Unless I know what beauty is I can never loathe what is ugly. It

follows from this that I try to know you insofar as I can know myself; and

enjoying the knowledge of you does not mean that I lack self-knowledge. It is a

good thing, then, and singularly beneficial for my soul, that confessions of

this sort allow my persistent search for your light to dispel the darkness of

my reason. With steady lighting my reason will no longer be in the dark about

itself.

This beautifully written passage neatly expresses Guibert’s

purpose in writing the book – to try and understand himself in order to be able

to understand God. Right from the outset this is a deeply religious exercise,

but Guibert doesn’t want a generic understanding of what God is like and what

he does? He wants to understand him through his own personal experiences.

In the second chapter, Guibert goes on to think about the gifts

God has given him in life. This is echoing St Augustine, who in Confessions 9.6

says:

Original Latin: Munera tua tibi confiteor, domine deus

meus, creator omnium et multum potens formare nostra deformia.

My translation (bit ropey, but here goes): I demonstrate

many of your gifts to me to you, my lord God, creator of all and with much power

to shape our many deformities.

Here, Guibert remarks that all the things we have materially

in life are gifts from God and thus we shouldn’t boast of them because whatever

they might do for us in this world, they’ll do nothing for us in the next:

The more fleeting they are, the more their very

transitoriness makes them suspect. If one can find no other argument to despise

them, it is enough to point out that one’s genealogy, or physical appearance,

are not of one’s choosing.

Some things can sometimes be acquired through effort:

wealth, for example, or talent … But the truth of my assertion here is only

relative. If the light, which “enlightens the way for every man coming into the

world” [John 1.9] fails to enlighten reason – and if Christ, the key to all

science, fails to open the doors of right doctrine – then, surely, teachers are

fighting a losing battle against clogged ears. Any person, then, is unwise to

lay claim to anything except sin. But let me drop this and get on with my subject.

Guibert then goes on name the first and foremost of those

gifts God has given him, namely his mother “who is beautiful yet chaste and

modest and filled with the fear of the Lord”, which nicely summarises Guibert’s

view of what womanhood should be (he most certainly wasn’t alone in it!).

Guibert’s mother is a very important recurring character in the Monodies,

as we’ll see, and it is she who plays the most important role, after God of

course, in steering him down the right path and away from sin and ruin. It becomes

quite clear from the Monodies that Guibert was very close to his mother

(even after he become a cloistered novice monk, she lived as a hermit in the

monastery grounds and he would visit her), and that she had a very important

influence on his personality, both positive and negative. It was no doubt his recollections

of his mother that led to Guibert identifying a lot with St Augustine, who also

had a mother (Monica) who was devout and modest, whom he was very fond of and

who did a lot to try and steer him down the right path, in Augustine’s case

towards Christianity (Augustine’s father was a pagan and in youth Augustine became

firstly a Manichaean and then a Neoplatonist sceptic).

Guibert uses his mother to illustrate the points he’s just

made earlier:

Mentioning her beauty alone would have been profane and

foolish if I didn’t add (to show the vanity of the word “beauty), that the

severity of her look was sure proof of her chastity. For poverty-ridden people,

who have no choice about their food, fasting is really a form of torture and is

therefore less praiseworthy; whereas if rich people abstain from food, their

merit is derived from its abundance. So it is with beauty, which is all the

more praiseworthy if it resists flattery while knowing itself to be desirable.

Sallust was able to consider beauty praiseworthy

independent of moral considerations. Otherwise, he would have never said about

Aurelia Orestilla that “good men never praised anything in her except her beauty.

Sallust seems to have meant that Aurelia’s beauty, considered in isolation,

could still be praised by good people, while admitting how corrupt she was in

everything else. Speaking for Sallust, I think he might as well have said that

Aurelia deserved to be praised for a natural God-given gift, defiled though she

was by the other impurities that made up her being. Likewise, a statue can be

praised for the harmony of its parts, no matter what material it is made of. Saint

Paul may call an idol “unreal” from the point of view of faith, and indeed

nothing is more profane than an idol, but one can still admire the harmony of

its limbs …

… If everything that has been designed in the eternal

plan of God is good, every particular instance of beauty in the temporal order

is, one might say, a mirror of that eternal beauty. It is created things that

make the eternal things of God intelligible,” [Romans 1:20] says Saint Paul …

In his book entitled On Christian Doctrine (If I am not

mistaken) Saint Augustine wrote something like this: “a person with a beautiful

body and a corrupt soul is to be more pitied than one whose body is also ugly.”

If therefore we lament beauty that is blemished, it is unquestionably a good

thing when beauty, though depraved, is improved through perseverance in

goodness.

Thank you God, for instilling virtue in my mother’s

beauty. The seriousness of her whole bearing was enough to show her contempt

for all vanity. A sober look, measured words, modest facial expressions hardly

lend encouragement to the gaze of would-be suitors. O God of power, you know what

fame your name had inspired in her from earliest years, and how she rebelled

against every form of allurement. Incidentally, one rarely, if ever, finds

comparable self-control among women of her social rank, or a comparable

reluctance to denigrate those who lack self-control. Whenever anyone, whether

from within our outside her household, began this sort of gossip, she would

turn away and go, looking as irritated as if she were the one being attacked.

What compels me to relate these facts, O God of truth, is not a private affection,

even for my mother, but the facts themselves, which are far more eloquent than

my words could ever be. Besides, the rest of my family are fierce, brutish

warriors and murderers. They have no idea of God and would surely live far from

your sight unless you were willing to show them your boundless mercy as you so

often do.

|

| "Fierce and brutish warriors and murderers" with "no idea of God": knights torment the Roman philosopher and statesman Boethius in this highly imaginative eleventh century manuscript of the Consolations of Philosophy from France, Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Latin 6401 |

There’s so much to talk about here. The first is Guibert’s

methods of argumentation. He always starts from his own personal reflections on

human character, which he seems to have a keen awareness of, or on God and then

elaborates on them with references to revered authorities – a standard method

of argumentation throughout Antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance,

given how much tradition and ancient wisdom was valued in premodern thought. Most

of the intellectual authorities Guibert cites are the Biblical, or else St

Augustine, though notably he does cite the first century BC Roman historian Sallust,

specifically his discussion of Aurelia Orestilla, the wife of the wicked

Catiline, the Roman aristocrat who attempted to overthrow the Republic in 63

BC, in his On the Conspiracy of Catiline. We might assume, based on our preconceived

modern stereotypes, that a devout medieval monk would be hysterically opposed

to pagan literature, but as I’ve written before such stereotypes are largely

unwarranted. Instead, the pagan Romans were regarded by most medieval intellectuals

as the best guide to skilled rhetoric and fine writing, and as deeply insightful

if sometimes flawed guides to the natural world, the human condition and history.

Sallust himself was a standard classroom text in medieval monasteries and

cathedral schools, and so many medieval historians roughly contemporary to Guibert

including William of Poitiers, Bruno of Merseburg, Orderic Vitalis, William of

Malmsbury and Henry of Huntingdon were intimately familiar with both his Catilinarian

Conspiracy and his Jugurthine War. In citing Sallust, Guibert was

both showing that the ancients had made the similar observations on human

character to him, despite their differing religious worldviews, as well as also

demonstrating that he was a well-educated man.

We can also see that Guibert wasn’t dogmatic in how he chose

to follow authorities. While he agrees with Saint Paul that idols, by which he

means physical objects that are worshipped by people presuming them to be

living, physical manifestations of deities, are bad, he also says that they can

nonetheless be pleasing to look at from an aesthetic standpoint. This also reflects

part of his personality – as I’ll show you in a future post, Guibert did have something

of a proto-archaeological interest in pagan antiquities, and even excavated a more

than one thousand-year-old holy-site in the grounds of his monastery.

The final lines concerning his mother in this chapter really

give us a sense of why Guibert wrote the Monodies. These “facts” about his

life do more than any abstract theological reasoning or fine rhetoric could do

to illustrate his arguments, by showing how it all works out in the here and

now.

Guibert also has a very negative attitude towards his own

family background and social class. As we’ll see, both his parents came from

the lowest echelons of the Northern French warrior aristocracy – his mother was

a minor noblewoman and his father a knight who owned his own castle. While

undoubtedly this background helped Guibert get to where he was, as abbot of Nogent,

Guibert sees it as nothing praiseworthy and disdains what he sees as the highly

secular, materialistic and violent culture of this social group. Guibert was not

alone here. St Bernard of Clairvaux, the great Cistercian abbot and the most

influential religious leader of the twelfth century, was full of denunciations

of the vanity, vainglory, lustfulness and violence of nobles and knights – in

1115, a year after Guibert finished the Monodies, Bernard condemned the

new craze for mock battles among young knights that were coming to be known as

tournaments. And Guibert’s contemporaries, Orderic Vitalis and Abbot Suger, wrote

invective-laden narratives about borderline psychopathic feudal lords who

habitually terrorised churches and kidnapped and tortured merchants, men like

Robert de Belleme and Thomas de Marle (who also appears in Guibert’s Monodies).

At the same time, Guibert is a helpful reminder that churchmen and warrior aristocrats

weren’t from two different worlds – a lot of the time, they were brothers,

uncles, nephews and cousins! And the First Crusade gave Guibert a flicker of

optimism for the warrior elite, while his contemporary St Bernard of Clairvaux

tried to spiritually reform them and channel their martial energies to higher causes

by setting up the Knights Templar with Hugh de Payens between 1118 and 1127.

Finally, Guibert gives us such a brilliant insight into the

ascetic mindset, which can be really hard to grasp in twenty-first century

Britain where the idea of going off to live in a monastery, giving up all

personal property, abstaining from sex and living a life of prayer, hard work,

study, contemplation and fasting to get closer to a divine being seems very

alien and transgressive to most people. Particularly revealing is that paragraph

about poor people fasting as opposed to rich people fasting, the latter

deserving more praise than the former for doing so. A recurring theme

throughout many medieval hagiographies is the wealth, noble pedigree and

physical attractiveness of the saints (male and female) that are their subject

matter being stressed – the point being that they could enjoy political power,

luxurious living and sexual pleasure, yet they chose to spurn it all to pursue

a higher cause. Perhaps then the closest analogues to medieval ascetic saints

and monks today would be certain members of the environmental movement, like

Greta Thunberg.