And so we're back again with another Carolingian imperial coronation, one which followed almost exactly 75 years after the one we looked at last time and one which was very much meant to replicate it. And this post concerns probably my favourite Carolingian monarch of them all, Charles the Bald.

On this day in 875, King Charles the Bald of West Francia was crowned Western Roman Emperor at Rome by Pope John VIII, having been crowned King of Italy and received the imperial regalia at the Italian capital, Pavia. On 12th August 875, Charles' nephew, Louis II, the king of Italy and the Western Roman Emperor, had died aged 50. His only child was a daughter, Ermengard. With the death of Louis II, the branch of the Carolingian family descended from Charles' elder brother, Lothar I (795 - 855), became extinct. This was a crucial step in the "great-thinning out" (as I call it) of the Carolingian dynasty. In 862, there had been five Carolingian monarchs (six if we include the usurper Pippin II in Aquitaine), each with the potential to start their own royal line in their respective kingdoms - there's also a seventh branch of the Carolingian family, the counts of Vermandois (descended from Charlemagne's middle son, Pippin of Italy) but we don't talk about them. By 875, it had already narrowed down to two - the West Frankish branch descended from Charles the Bald and the East Frankish branch descended from Charles' middle brother, King Louis the German of East Francia. By 911, there would be just the one branch, Charles the Bald's branch, which would continue to rule in West Francia, with some interruptions, all the way up to its termination in 987 - again, the Vermandois branch survived into the eleventh century and indeed beyond (they're also the female-line ancestors of William the Conqueror and all English monarchs since 1066, not to mention a huge chunk of the British aristocracy), but for the last time no one talks about them!

Now, like when King Lothar II of Lotharingia died, also childless (save for an illegitimate son, Hugh of Alsace) in 869, Louis II's uncles immediately pounced and tried to get first dibs on his kingdom and the imperial title. Charles managed to win the race and so he was crowned King of Italy and Western Roman Emperor on this day in 875.

In a way, this was the fulfilment of Charles' lifelong ambition. Though Charles, unlike his three elder brothers, had never personally known his grandfather, the Emperor Charlemagne (d. 814), he did grow up with him as a role model. In 829, when Charles was eight, one of his father's court poets and leading advisers, Walahfrid Strabo, wrote in his poem "Concerning the vision of Tetricus":

Happy the line that continues with such a grandson: grant Christ that he will follow in deeds whom he follows in name, in deed, in character, nature, life, virtue and triumphs, in peace, faith, piety, intellect, speech and dignity. In doctrine, judgement, result and in loyal offspring.

Janet Nelson has suggested in her 1992 biography of Charles the Bald, still the definitive work on the Carolingian monarch 30 years on, that Einhard's "Life of Charlemagne" was used as a mirror for princes in the 830s to provide the teenaged Charles with an education in political theory. Certainly, Charles had read Einhard's "Life of Charlemagne", as he quoted directly from it in a letter that he himself composed for Pope John VIII, shortly before his death in 877 at the age of 56. And all throughout his life, his courtiers were always trying to measure him up to Einhard's portrayal of Charlemagne as neo-Roman Emperor in the mould of Augustus Caesar, Vespasian and Titus.

This can also be nicely illustrated by comparing Charles to his middle brother, Louis the German (806 - 876). While the East Frankish king issued no legislation and kept his administration simple, he excelled in diplomacy and warfare, especially on his long eastern frontier with the Slavic realms extending all the way from the Baltic to the Adriatic. He was also very good at managing his sons, extended family and aristocracy, and never faced serious challenges to his rule from any of them in his 33 year long reign in East Francia. He also ruled much of his realm with a very light touch - he rarely set foot in the roadless, densely forested and still semi-pagan and tribal region of Saxony, but when he did in 852 he held public judicial assemblies (placita in the Latin sources) and his subjects eagerly petitioned him for dispute resolution and favours. Charles the Bald, on the other hand, was the opposite - the first twenty years of his reign in West Francia saw him experience revolts from both his sons, his extended family (his nephew Pippin II) and his aristocrats, and he wasn't all that militarily successful against the Vikings and Bretons and his East Frankish relatives. But Charles had a near-boundless vision. His legislation testifies to it - the Edict of Pitres in 864, which I've talked about here before, was the most lengthy and ambitious single piece of legislation any Western European ruler ever issued between the fifth and the thirteenth centuries. The Carolingian project of governmental reform and centralisation probably peaked under him - the coinage was very successfully reformed and put under tighter control, the foundations for a new system of national taxation (the first Francia had known since the old Roman tax system decayed in the seventh century), military service was extended to most of the free male population and missi continued to investigate the localities to ensure public justice was running smoothly and enquire into corruption and abuses with more vigour than ever. Royal assemblies, probably the most important institution of Carolingian government, were also at their grandest in his reign - Charles the Bald and his main adviser, Archbishop Hincmar of Rheims (806 - 882) were absolutely obsessed with ritual. Charles was also a real intellectual, who had extensively studied law, theology and Roman history since childhood, and during his reign the Carolingian project of expanding education and literacy and the influence of intellectuals at court continued to thrive.

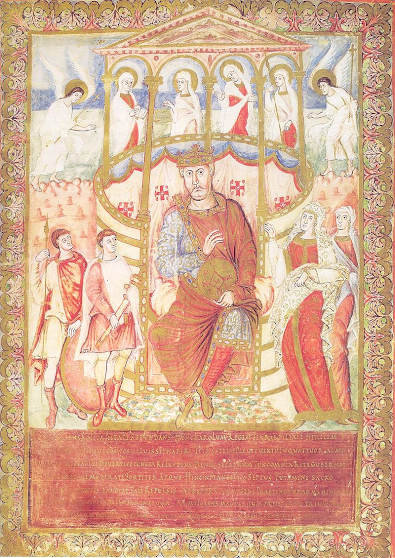

The image below, from the Psalter of Charles the Bald, produced c.869 by an artist in Charles' Palace School, nicely illustrates how this had always been Charles' great ambition. It shows Charles enthroned and dressed in an ankle-length tunic and chlamys like a contemporary Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Emperor. He has a crown on his head (a symbol of kingship since Biblical Israel) and he carries the orb and sceptre, symbols of rulership that seem to have developed under the Carolingians in the late eighth and ninth centuries, symbolising his authority over the world granted to him by God. He also sits underneath a canopy in the classical Roman architectural style. The inscription in Latin, written in the square capitals used for monumental inscriptions in ancient Rome (as the Carolingians would have known very well), reads:

When Charles the Great presides with his crown on, he is similar in honour to Josiah and the equal of Theodosius.

|

| Ca. 869 AD. BnF, Manuscrits, Latin 1152 fol. 3v, École du Palais de Charles le Chauve, Wikipedia Commons |

Thus Charles the Bald is consciously being compared to three of his personal heroes here - the seventh century BC Old Testament King Josiah of Judah, a great reformer of Judaism who compiled the books of the Torah together; the Christian Roman Emperor Theodosius I or II, the former being the one who made Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire and the latter being the one who codified Roman law into the Theodosian Code which Charles the Bald cites regularly in the Edict of Pitres; and the third being his grandfather Charlemagne.

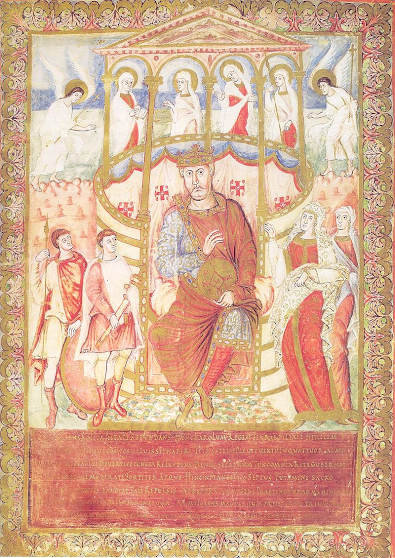

Indeed, at the month-long Synod of Ponthion in June 876, Charles the Bald would come dressed in the traditional Frankish costume of knee length tunic, cloak and leggings at the start, but by the end was dressed exactly how he is in that image - in the East Roman imperial costume and with a crown. His wife, Queen Richildis, was then given her coronation as Empress. This was done to make it real to the West Franks that Charles was now Emperor. The image below, from the San Paolo Bible, nicely illustrates how he would have appeared.

|

| By Benedictine workshop, probably in the Reims region. - Bible of San Paolo fuori le Mura, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7590481. I would translate the inscription if it wasn't too damn faded. But its a masterpiece of Carolingian art all the same, especially rich in its use of colour and decorative patterns. |

Finally, Charles also had a splendid throne made for his coronation. It survives in the Vatican museum, and is richly decorated with carved ivories. Below you can see the throne itself, and individual panels from it. They depict episodes from the labours of Hercules, including Hercules wrestling the Nemean lion and cleaning out the stable of Diomedes. This is demonstrative of how Charles and his court absolutely adored classical literature and mythology, and how Charles saw parallels between his own triumphs and tribulations as king and emperor and those of the greatest of the Greek heroes. But it may also be a warning, perhaps even influenced by Theodulf's poem we looked at earlier this year, against the dangers of pride and trusting too much in your own abilities rather than in God to give you success, which Hercules exemplified. Indeed, Charles himself was guilty of this on many occasions, as his attempt to reunify the entire Carolingian Empire by conquering East Francia ended disastrously at the battle of Andernach on 8 October 876. His imperial glory was also fleeting too, as he enjoyed it for only two years before his death in 877.  |

| Photo credit: Helen Gittos https://twitter.com/Helen_Gittos/status/1398695600854536193/photo/1

|

Bibliography:David Ganz, "Introduction" in Einhard and Notker the Stammerer, Two Lives of Charlemagne, edited and translated by David Ganz, Penguin Classics (2008)

Janet Nelson, Charles the Bald, Longman (1992)

Chris Wickham, The Inheritance of Rome: A History of Europe from 400 - 1000, Penguin (2009)

No comments:

Post a Comment