|

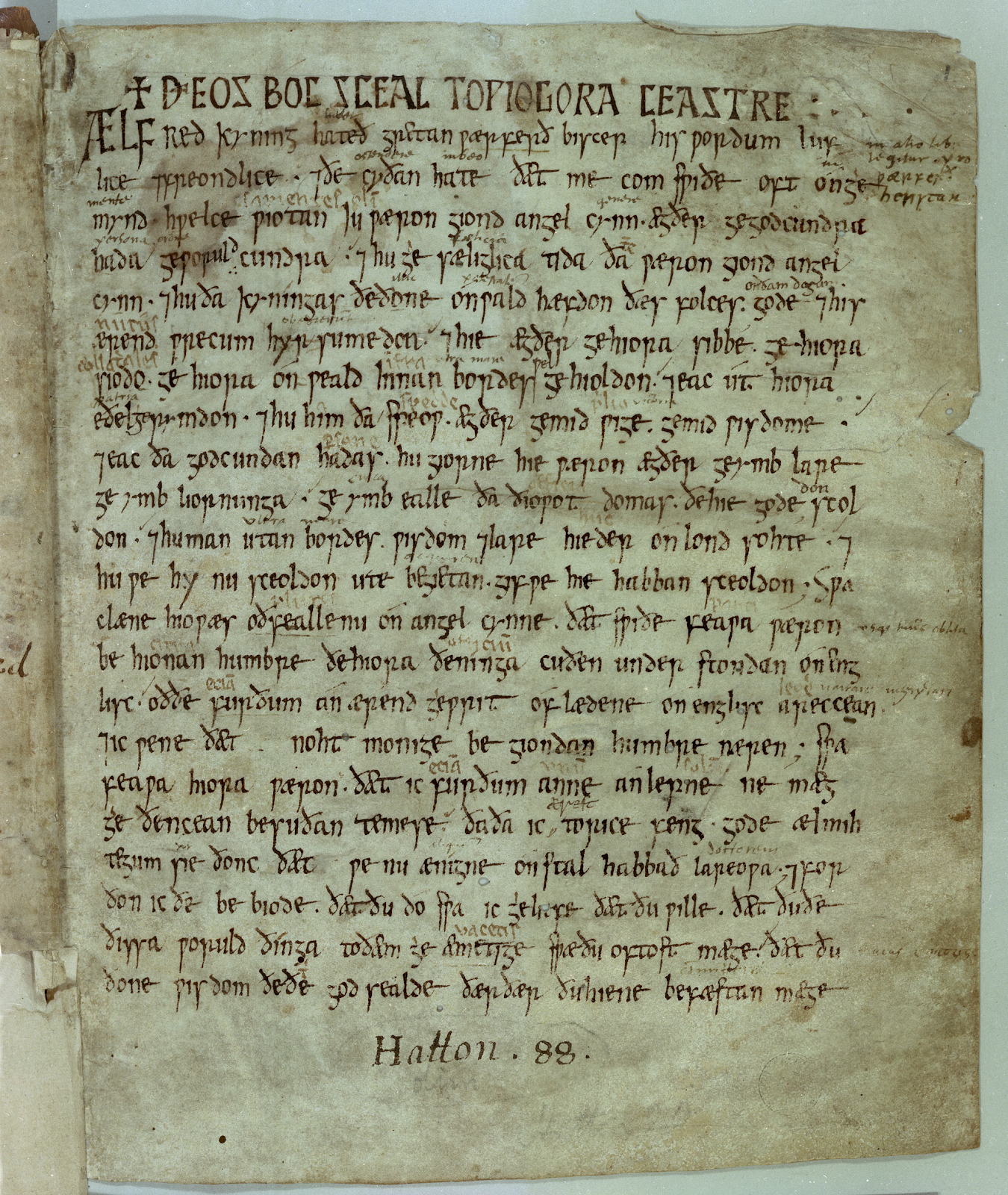

| The most enigmatic scene from the Bayeux Tapestry. A cleric in secular clothing touches the face of a mysterious woman called Aelfgyva in a bizarre intermission from the story of Harold Godwinson's visit to Normandy in 1064. Some think its an allusion to a notorious sex scandal at the time - it looks like the cleric is amorously caressing Aelfgyva, and in the border below a naked man is touching his genitals. The Bayeux Tapestry was most likely made between 1068 and 1070, not long after the time Guibert's family started searching for a church prebend for him. |

So last time I gave my best attempt at a crash course on the

papal revolution. But now let’s zoom back into the juicy details of Guibert’s

autobiography and see how all this played out at the grass roots.

We’ll firstly revisit that quote from Guibert that was the

stumbling block that led us on to the papal revolution:

At that time, the Holy See had initiated a new attack

against married clerics. Consequently, some zealots began railing against these

clerics, claiming that they should either be deprived of ecclesiastical

prebends or forced to abstain from priestly functions.

Now the specific moment in the papal revolution that Guibert

is referring to when he says “at that time, the Holy See had initiated a new

attack against married clerics” is in the spring of 1059, when Pope Nicholas II

convened the Synod of Rome. This was a key point of escalation in the papal

reform movement, as one of the most important outcomes of the synod was the

creation of the college of cardinals to elect the pope – until 1059, popes had

been installed on the throne of St Peter either by the emperor, the

aristocratic clans of Lazio or by the Roman citizen mob. But it was also there

that he continued what Leo IX did at Rheims in condemning simony, though he

went a step further in outlawing all lay investiture even from the German

emperor, who could continue to invest bishops once he had acquired that right

from the Pope – this would be key in leading up to the struggle between Emperor

Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII. But what it also did was condemn clerical

marriage, by forbidding any deacon or priest known to live with a woman from

assisting and celebrating at the Mass. And as Guibert indicates clearly in this

passage, these measures were widely supported by ordinary lay Catholics.

|

| Early twelfth century fresco of Pope Nicholas II at the basilica of San Clemente Laterano in Rome, appearing no doubt as he did when he issued the legislation outlawing clerical marriage at the Lateran Council, which took place almost in the exact location where this fresco is, in 1059. |

This event would have been one of the most discussed and

divisive political events of Guibert’s childhood, almost like 9/11, the wars in

Afghanistan and Iraq, the 2008 financial crash, the election of Obama, the

Coalition’s Austerity programme and the raising of tuition fees, the Arab

Spring and the Syrian Civil War, Brexit and the rise of Donald Trump were for mine.

And it really does testify to the growing power of the papacy that for the

first time since the days of the Roman Empire, decisions made in Rome could be

have effects on minor provincial towns in Northern France. But what’s also so

interesting about this is that Guibert, despite being a serious Benedictine

monk who struggled with self-loathing and guilt about his own sexual urges,

finds the idea that clerics should be celibate too quite horrifying. You can

tell from the language he uses to describe the campaigners against clerical

marriage not as heroic moral reformers but as crazy fanatics trying to force

good decent people to accept their ideology. Sounds almost familiar, doesn’t

it! Indeed, as I’ll no doubt show you in future posts, Guibert was in many ways

quite a conservative writer, who did not like the way politics, society and

culture were headed. But why was the idea that deacons and priests should not

have wives or have sex so radical?

Of course, contrary to what some historians specialising in

the high and later Middle Ages (1050 – 1500), especially those specialising in

sexuality and gender, tend to think, this wasn’t an idea that had come

completely out of blue. Instead, the idea that clerics must be celibate had

been floating around for a very long time. Here we are of course wading into

incredibly theologically sensitive territory, as Catholics view clerical

celibacy as an ancient and unshakeable apostolic tradition, whereas Protestants

see it as an evil papistical innovation lacking in any Biblical foundation

whatsoever which leads priests down the path of sin because they don’t have the

right outlet for their natural urges (the marriage bed). Greek and Russian

Orthodoxy sit between the two extremes. Bishops in Eastern Orthodox are

generally not allowed to marry – indeed, they are often expected to be former

monks. But ordinary priests and deacons are allowed to marry and have children,

though they are expected to get married before their ordination, and this has

been the tradition in Eastern Orthodoxy since the Middle Ages. Indeed, going

back to late antiquity, the morals of priests has always been much more of an

issue in Latin (Western) Christianity than in Greek (Eastern) Christianity. To

Greek Christians in the fourth to seventh centuries, what mattered most to a

church congregation was whether or not your priest believed in the correct

theological doctrines, especially concerning the nature of Jesus Christ

(whether he was more divine or human, or equally both). Whereas to Latin

Christians in that period, and ever since, the question that mattered most was

“is my priest a good man?” This is one of the many super-insightful things that

Chris Wickham brings up in the “Inheritance of Rome”, which I’m still reading

for fun at the moment.

The New Testament doesn’t say anything in favour of clerical

celibacy. While, unless you’re Dan Brown, it is indeed true that Jesus of

Nazareth himself was not married and never had sex, some of his disciples

undoubtedly were. Matthew 8:14 mentions Jesus healing Peter’s mother-in-law –

the first Pope was therefore a married man. St Paul in his First Epistle to the

Corinthians 9:5, mentions that two of the other original twelve apostles,

Jesus’ brothers James and Simon, were also married. And so far as we can tell from

what Jesus says in the Gospels, he had nothing bad to say about marriage.

However, St Paul, without whom Christianity would have

remained an obscure Jewish sect, had an ambivalent view of marriage. He may

have been married before he went on the Road to Damascus, but by the time he

was spreading the word of Jesus and writing his epistles he was single. Also,

and this is really crucial, St Paul argued that being a lifelong virgin was the

best possible choice for a Christian – in Corinthians 7:1 he wrote “it is good

for a man not touch a woman.” This was because he believed that virgins had

greater devotion to God than married men and women. In Corinthians 7:32 – 34 he

wrote “He that is unmarried careth for the things that belong to the Lord, how

he may please the Lord: but he that is married careth for the things of the

world, how he may please his wife. There is difference also between a wife and

a virgin. The unmarried woman careth for the things of the Lord, that she may

be holy both in body and in spirit: but she that is married careth for the

things of the world, how she may please her husband.” But this doesn’t mean

that St Paul opposed marriage outright. Instead, he argued that men and women

should marry if they couldn’t contain their lust, because that way they’d avoid

sinning. As he wrote in Corinthians 7:8 – 9 “it is good for them if they abide

even as I. But if they cannot contain, let them marry: for it is better to

marry than to burn.” And, and this is crucial to what we’re focusing on here, he

did not advocate for clerical celibacy. In his First Epistle to Timothy 3:2, he

wrote “A bishop then must be blameless, the husband of one wife, vigilant,

sober, of good behaviour, given to hospitality, apt at teaching.” Its safe to

say that this job description for priests and bishops was the one most widely

held to by Christian communities in the first three centuries of Christianity.

Where things really started to change was in the fourth

century AD, when as we said before bishops stopped being just local community

leaders and essentially became officials under the patronage of the Roman

Emperor following the conversion of Constantine the Great. That in itself

didn’t do anything to endanger clerical marriage, but the more Christianised

late Roman society became, the more issues flared up. Along with the rise of

the first Christian monks and hermits, an ascetic invasion took place in which

the ranks of the bishops and other church leaders came to be filled with

admirers of these holy men and women who believed that virginity was

spiritually superior to marriage. I can’t possibly do justice to explaining the

rise of Christian asceticism, all I can say is read literally anything by Peter

Brown (a living legend) as he’s been the undisputed expert on this stuff for

the last fifty years. Among the biggest supporters of asceticism were St

Ambrose of Milan, St Martin of Tours, St Jerome and St Augustine of Hippo. They

were opposed by many people, including Jovinian, who argued that marriage and

virginity were equally good and thus had a lengthy spat with Jerome over it. By

the end of the fourth century, the ascetics had definitely won out over their

enemies and almost all the writings of the anti-ascetic faction in late antique

Christianity do not survive to us today, either being targeted for destruction

or simply neglected over the centuries. And in the 390s, Pope Siricius made the

first decree advocating celibacy for priests. Thus, by c.400 AD, clerical

celibacy was the official ideological position of the Western Church and that

did not change.

Did that decree actually make clerical marriage illegal and

lead to any kind of systematic clampdown on married clerics. The short answer

is, actually no. In the East, Pope Sicirinus was completely ignored and Greek

Christianity has always officially allowed married priests, as I said before.

But in the West too, for the next 600 years, clerical marriage was incredibly

common and most of the time in most places basically tolerated. Indeed, it

became normal for priests and even bishops to treat their churches as property

that they could pass on to their sons. A good example is Archbishop Milo of

Trier (d.753), who was a close ally of Charles Martel and may have been the

uncle of Pippin Short (Rotrude of Hesbaye, Pippin’s mother, is his putative

sister), both long-time friends of this blog. Milo was the son of Archbishop

Leudwinus of Trier and his wife Willigard of Bavaria. He likewise had lots of

children with his wife, and became the archnemesis of St Boniface, who

disapproved of his worldly and warlike personality – fittingly enough, Milo

died during a boar hunt. Not far from Trier, Archbishop Gewilib of Mainz was

also married and was the son of Archbishop Geroldus. Gewilib was another

warrior, who avenged his father after he fell in battle against the Continental

Saxons on Charles Martel’s campaigns by slaying the Saxon warrior who killed

him. He fell afoul of Saint Boniface too, and was deposed by him – back in St

Boniface’s home country, Anglo-Saxon England, bishops were predominantly monks

and therefore could not possibly be married. Some historians see a shift

against clerical marriage, and certainly some Carolingian reformers were

against it. For example, our friend Theodulf of Orleans wrote in the precepts

for his diocese:

Let no woman live with a presbyter in a single house.

Although the canons permit a priest’s mother and sister to live with him, and

persons of this kind in whom there is no suspicion, we abolish this privilege

for the reason that there may come, out of courtesy to them or to trade with

them, other women not at all related to him and offer an enticement to sin with

him.

Emperor Charlemagne’s own legislation left the situation

much more ambiguous. In his General Capitulary for the Missi in 802, he wrote:

If, moreover, any priest or deacon shall presume

hereafter to have with him in his house any women except those whom the

canonical licence permits, he shall be deprived of both his office and

inheritance until he be brought into our presence.

It is unclear whether the women included in the “canonical

licence” for are just a priest’s blood relatives, or whether that would also

extend to a lawfully wedded wife. Meanwhile the Penitential of Bishop Halitgar

of Cambrai, written in the 830s, says a bit more clearly:

If after his conversion or advancement any cleric of

superior rank who has a wife has relations with her again, let him be aware

that he has committed adultery. He shall do penance with the foregoing

decision, each according to his order.

What Halitgar meant by a cleric of superior rank is unclear.

But what he’s saying is that if these clerics get ordained whilst still being

married men, that’s fine, its just that they must swear off having sex once

they’ve acquired their church positions.

Still, in the Carolingian period we continue to find plenty

of married bishops, just as we also find plenty of bishops who led armies into

battle and fought as warriors despite St Boniface’s condemnations of it in the

740s. Indeed, even Pope Hadrian II (r.867 – 872) was a married man with

children, who remained married, sexually active and a family man after being

appointed to the papal office. And among ordinary village priests and other

lesser clerics, clerical marriage was normal and mostly unchallenged. We saw

some of that in the Marseille Polyptych in 814. And as we go into the tenth

century, we continue to see clerical marriage and priestly dynasties

flourishing both inside and outside the former Carolingian Empire. In the

cartulary of Redon in Brittany in the early tenth century, we see lots of

priests passing down their offices to their sons for generation after

generation. We can find lots of similar evidence from tenth century England,

Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Northern Italy and Spain. The evidence from

Anglo-Saxon England for clerical marriage in the period 900 - 1066 is

plentiful, and most named priests in this period seem to have been the sons of

priests, many of whom inherited the exact same church offices as their fathers,

as painstaking research by Julia Barrow has shown. Indeed, many of these

priestly dynasties in Anglo-Saxon England continued even after the Norman Conquest

brought the papal revolution to England. William the Conqueror and Archbishop

Lanfranc seem to have only really taken action against married bishops, like

Leofwine of Lichfield (deposed in 1071), which is a big contrast to Normandy

where clerical celibacy did make some headway in the late eleventh century,

despite much division over it. Only in the century after 1150 did church

reformers really succeed in imposing celibacy on English cathedral canons and

parish priests. As a result, many churches in Anglo-Saxon and Norman England

were basically the property of these priestly dynasties. For example, when the

incumbent priest of All Saints’ church in Lincoln tried to give the church to Peterborough

Abbey when he decided to become a monk there, the citizens wouldn’t allow him

to remove it from the ownership of his family unless King William consented, a

case which is recorded in the Domesday Book.

|

| All Saints' Greetwell, Lincoln, today. Though the church saw some alteration in the nineteenth century, most of the eleventh century building is clearly visible. |

A really good example of a clerical dynasty working in

practice is the hereditary priests of Hexham in Northumberland, a father, son

and grandson who held the parish church in succession from 1020 to 1138. The dynasty

began with Alfred, who was also sacrist of Durham cathedral from 1020 until his

death in 1041. He married the sister of Collan II, provost of Hexham to the bishop

of Durham from 1042 to 1056, and together they had three children: Eilaf, who

succeeded his father at Hexham; Hemming, who became priest of Brancepeth no

later than 1055; and Ulkill, who was priest of Sedgefield no later than 1085.

Eilaf, like his father, held an important position in the bishop’s

administration as well, and from his marriage he had two sons: Eilaf Junior,

who succeeded him as priest of Hexham; and Ealdred, who was a canon at Hexham Priory.

Eilaf Junior became the new priest of Hexham in 1086, the year of the Domesday

Book, and kept the office until his death in 1138, the year the Scots invaded

Northumberland and were defeated at the Battel of the Standard.

Thereby, while the idea of clerical celibacy had been around

for a long time, and influential in a lot of circles, and past precedent

certainly did matter – the papal revolutionaries certainly did look back to the

late Roman world, when the first calls for clerical celibacy had emerged, for

inspiration a lot. Still, it had never been the norm down to the eleventh

century. Thus, it was a genuinely shocking idea for a monk, someone who professionally

had to be in favour of abstaining from sex, like Guibert, when the papacy launched

a campaign to make clerical marriage illegal in all of Latin Christendom in 1059.

Why the Papal revolutionaries would choose to target clerical

marriage as one of the main evils to uproot does deserve explanation. Apart

from the ideological precedents given by late Roman and Carolingian churchmen,

the main attraction of it all came with the idea of bringing all churches and

their property under the control of the Church as a multinational corporation

and being able to control who was appointed to them. This you could not do if dynasties

of hereditary priests existed (the natural consequence of clerical marriage),

just like you could not do it if churches were under control of kings and

feudal lords (lay investiture) or if people could just buy their way into

clerical office (simony). The other underlying reason, going back to the

letters of St Paul which we saw earlier, is the idea that you can only be fully

devoted to God if you have no distractions, one of which being marriage and family

life. Thus, if the papal revolutionaries wanted their priests to be as devout in

their service to God and unquestioningly loyal to the Church as a multinational

corporation as possible, they needed to deny them marriage and family life. Moreover,

celibacy would give the priests moral authority by demonstrating high levels of

self-control, just as it had given monks and other holy men such authority in

centuries before. This would help them be the enforcers for the Church’s

broader programme for Latin Christian society as a whole.

The reasons why

people would want to resist this are as clear as day. Imagine you’re just a

regular parish priest somewhere in Northwest Europe sometime around 1100. You’re

living a comfortable and wholesome life with your wife, your son and three

daughters, all of whom you love to bits. All of a sudden, an order comes from

your local bishop, a former monk who has never married, that your marriage is not

a real marriage in either the eyes of God or the law. Therefore, you must separate

from your wife and children and never let them in your house again, or risk being

banned from performing church services and losing your property. People in your

local village or town start jeering and publicly shaming your wife, calling her

a concubine and a slut. All of your children are now bastards under the law and

the plans you carefully laid out for them have to be thrown out the window.

Your son can no longer train as a priest and succeed you. And no respectable young

man in the local community will want to marry your daughters. This goes in the

face of what was perfectly normal in your father and grandfather’s day, and you

know that priests, bishops and even popes in the early church were married. You

might feel tempted to tell him to f*** off and just carry on as you are. You

can try to reason with him, pointing to church history and morality – if you

can’t have a wife, your natural urges might lead you and other married clerics to

fornicate with, you know, actual prostitutes, a mortal sin. Or you might get

sympathetic neighbours to throw stones at the bishop or his agent. Or you might

even go about writing pamphlets and speeches suggesting that this all a

conspiracy by sodomite bishops and monks, trying to direct the new religious

fervour of the common people against good honest married clerics, while they’re

busy pulling and sucking each other off in their dormitories. All of these first

three responses to the reformers are attested Normandy in the last quarter of

the eleventh century by Orderic Vitalis, and the fourth response was taken by

the cleric and poet Serlo of Bayeux. Its notable that one of the main champions

of clerical celibacy in England, none other than Guibert’s former friend and

tutor Anselm of Canterbury, was almost certainly gay. As William of Malmesbury

wrote, at the Council of Westminster in 1102 there were going to be laws passed

against sodomy in the monasteries, but Archbishop Anselm suspiciously decided

not to promulgate them at the last minute. To many people at the time, reformers

championing clerical celibacy were nothing but rank hypocrites.

In many ways, this is a story that resonates with our own

times, in more ways than one, and historians writing about this period often

slip into casting one side as the goodies and the other as the baddies, depending

on their personal and political inclinations. The Gregorian reformers/ papal

revolutionaries can seem like the good guys, as stalwart progressives who were

trying to stamp out corruption and nepotism and make priests more upright and

accountable. On the other hand, their opponents among the parish clergy can

seem like the good guys, as honest, down-to-earth folks who were really doing

their duties as best as they could but had fallen victim to snobby aristocratic

bishops and hypocritical do-gooder monks who wanted to destroy established

traditions and local communities in the name of their radical ideology. Likewise,

both can seem like the bad guys in the face of twenty-first century

sensibilities. The Gregorian reformers were undoubtedly misogynistic,

essentially saying that women were to blame for bad priests and as soon as they

put them away the better, and some would say that clerical celibacy is directly

to blame for the current problem of child sex abuse in the Catholic Church. On

the other hand, their opponents resorted to what we would now recognise as homophobia

in their polemics against the reformers, and essentially held to the belief,

common among modern anti-feminist movements, that heterosexual men can’t

control their lust and that without a wife or a stable long-term relationship

they’ll shag any woman with a pulse. I’ve tried my best to be as impartial and

empathetic as I can to both sides. Guibert was impartial on the matter in his

own characteristically downbeat way, as we’ll see.

Now there were not one but two people helping bat for

Guibert in getting that church prebend at Clermont. The first was of course his

brother, a knight of the castle of Clermont whom the lord owed a debt. The

other was his brother, a layman whom the local bishop had illegally made abbot

of the very collegiate church where Guibert was going to get his prebend as a

priest. Guibert describes his cousin, whom he detested, thus:

It just so happened that one of these zealots was a

certain nephew of my father. This man, who was more powerful and cunning than

his peers, would indulge in sex like such an animal that he would never put off

having a woman when he wanted one, and yet to hear him rail against clerics

regarding this particular canon [the ban of clerical marriage], one would have

thought he was motivated by a singular modesty and distaste for such things …

He could never be chained to a woman through marriage, for he never intended to

be shackled by such bonds … Finding a pretence by which I might benefit at the

expense of a certain well-placed priest, he began pressing the lord of the

castle … For contrary to every law, human and divine, this man had been

authorised by the bishop to be the abbot of that very church. Thus, even though

he himself had not been canonically appointed, he was demanding of the canons

that they respect the canons.

Much like in Serlo of Bayeux’s polemics, here the supporters

of the papal revolution are hypocrites. All except here, the hypocrite in

question (Guibert’s cousin) is not a covert homosexual, but a red-blooded openly

promiscuous heterosexual. Guibert describes him both with vitriol and his

outstanding verbal wit and sense of irony, and in doing so sums up what many

people felt at the time about the reformers – that they were preachy and self-righteous,

but ultimately more morally bankrupt than the clerics they were trying to cast

aside.

What did the poor married priest, whose job Guibert’s

relatives were trying to steal to give to Guibert, do about this. Well, he took

the nuclear option. Beat these revolutionaries and fanatics at their own game

by turning their own principles against them. Guibert relates it thus:

At this time, it was not only a serious offence for

members of the highest orders and canons to be married, but it was also

considered a crime to purchase those offices involving no pastoral care … Those

who took the side of the cleric deprived of his prebend as well as many contemporaries

of mine, started murmuring about simony as well as the excommunications that had

recently proliferated.

Now if there was anything more sure-fire to bring the

ecclesiastical authorities and popular opinion on your side, it was accusations

of simony. As I’ve explained before, outlawing simony was a cause celebre of

the Gregorian Reform movement as well as imposing clerical celibacy. And most

people could get behind it on that. As I explained to my year 10s when I was

teaching them the church reforms of Archbishop Lanfranc as part of their Norman

Conquest GCSE unit, having a simoniac priest in the eleventh century would be

like having a local GP or a headteacher who had purchased their position rather

than getting it on merit now. It was absolutely scandalous, because the church

for people in the eleventh century was like the school system and the NHS for

us today and so they wanted priests who were honest, upright and well-qualified

for the job. And in trying to secure a church position for Guibert through a

debt his lord owed him, what was his brother doing other than well, you know,

simony of course. And from how Guibert describes it, in this way the married

priest was able to get public opinion on his side over an issue that had

clearly caught the attention of the citizenry of Clermont.

Even though he was a married priest, this man could not

be forced to part with his wife through the suspension of his office; but he

had given up celebrating Mass. Having given the divine mysteries less importance

than his own body, he justly escaped the punishment that he thought he had

escaped by renouncing the sacrifice. Once he was stripped of his canonical

office, there being nothing left to deter him, he began publicly celebrating

mass again while keeping his wife. Then a rumour spread that, in the course of

these ceremonies he pronounced excommunication on my mother and her family and

repeated it several days in a row. My mother, who always feared about divine

matters, feared the punishment of her sins and the scandal that might erupt.

She surrendered the prebend that had illicitly been granted and secured another

one for me from the lord of the castle in anticipation of some other cleric’s

death. Thus, do we “flee the weapons of iron, only to fall under the shafts of a

bronze bow [Job 20:24].” To grant something in anticipation of someone’s death is

hardly more than issuing a daily incentive to murder.

So the priest had successfully mobilised the local community

against Guibert’s family, and by publicly excommunicating them in front of a

crowd of the ordinary churchgoers who supported him, he was able to force them

to back down. What Guibert’s mother then did next horrified Guibert, and indeed

by the time Guibert wrote the Monodies, the practice of securing a

church position in anticipation of the incumbent’s death had been outlawed by

Pope Paschal II (r.1099 – 1118) at the Council of Beauvais in 1114. Thus, a would-be

victim of the papal revolution was able to use some of most important weapons

in its arsenal, accusations of simony and public opinion, against its very

zealots.

As Conrad Leyser, who was my tutor at Worcester College

during my undergraduate years has argued in a brilliant review article aimed at

specialists, this little anecdote nicely illustrates the significance of the

Gregorian reform movement as it was felt at the time. While it did nothing to

immediately eliminate patronage, proprietary churches, dynasticism and lay

aristocratic power from the church, decisions made in distant Rome nonetheless

affected how people jockeyed for clerical offices in obscure corners of

Northern France. Both sides appealed to the principles of the papal revolutionaries

in their struggle over the church prebend at Clermont, one side doing so more

successfully than the other, and both tried to get local public opinion, which

was becoming very influenced by these revolutionary ideas, on their side. Indeed,

in many ways this post and the two before it has been something of a homage to

Conrad, who I really enjoyed being taught by, as they’ve touched quite a bit on

his research interests and theories. Indeed, shoutout to Conrad if you happen

to be reading this – you provided me with three years of excellent teaching and

mentoring at Oxford, and you helped encourage and inspire me on my journey as a

medieval historian, even though I eventually decided academia wasn't the future for me.

Sources used:

A Monk’s Confession: The Memoirs of Guibert de Nogent,

translated by Paul Archambault, University of Pennsylvania Press (1996)

Carolingian Civilisation: A Reader, edited and

translated by Paul Edward Dutton, University of Toronto Press (2009)

Chris Wickham, The Inheritance of Rome: A History of

Europe from 400 – 1000, Penguin (2009)

Julia Barrow, The Clergy in the Medieval World: Secular

Clerics, the Families and Careers in North-Western Europe, 800 – 1200,

Cambridge University Press (2015)

R.I Moore, The First European Revolution, 970 – 1215,

Blackwell (2000)

H.A Freestone, The Priest's Wife in the Anglo-Norman

Realm, 1050-1150 (Doctoral thesis, 2018)

J.W Fawcett, “The Hereditary Priests of Hexham”, Hexham

Parish Magazine (1903), pp.37–38

https://notchesblog.com/2016/02/09/the-manly-priest-an-interview-with-jennifer-thibodeaux/

- post by Katherine Harvey, in conversation with Jennifer Thibodeaux

https://blog.oup.com/2014/09/clerical-celibacy/

- post by Hugh Thomas

Conrad Leyser, “Review article: Church reform – full of

sound and fury, signifying nothing?”, Early Medieval Europe, Volume 24 (2016),

pp 478 – 499