- Baptism is absolutely essential to making someone a Christian, and therefore everyone over the age of 1 year old must be baptised or face consequences.

- Christians must fast during Lent, attend Church on Sundays and celebrate Christian holy days by not working or attending any kind of public meeting other than religious services.

- Christians do not make human sacrifices, pray in sacred groves or bodies of water, burn witches or consult fortune-tellers - these superstitions make you a relapsed pagan in need of punishment.

- Christians must be buried in churchyards.

- Christians must live in a parish community and provide for their local priest, including by compulsory payment of the tithe.

Friday, 14 April 2023

From the sources 14: conquest, conversion and what it meant to be a Christian in the eighth century

Saturday, 11 March 2023

Controversies 2: the problem of early medieval literacy (the basics)

|

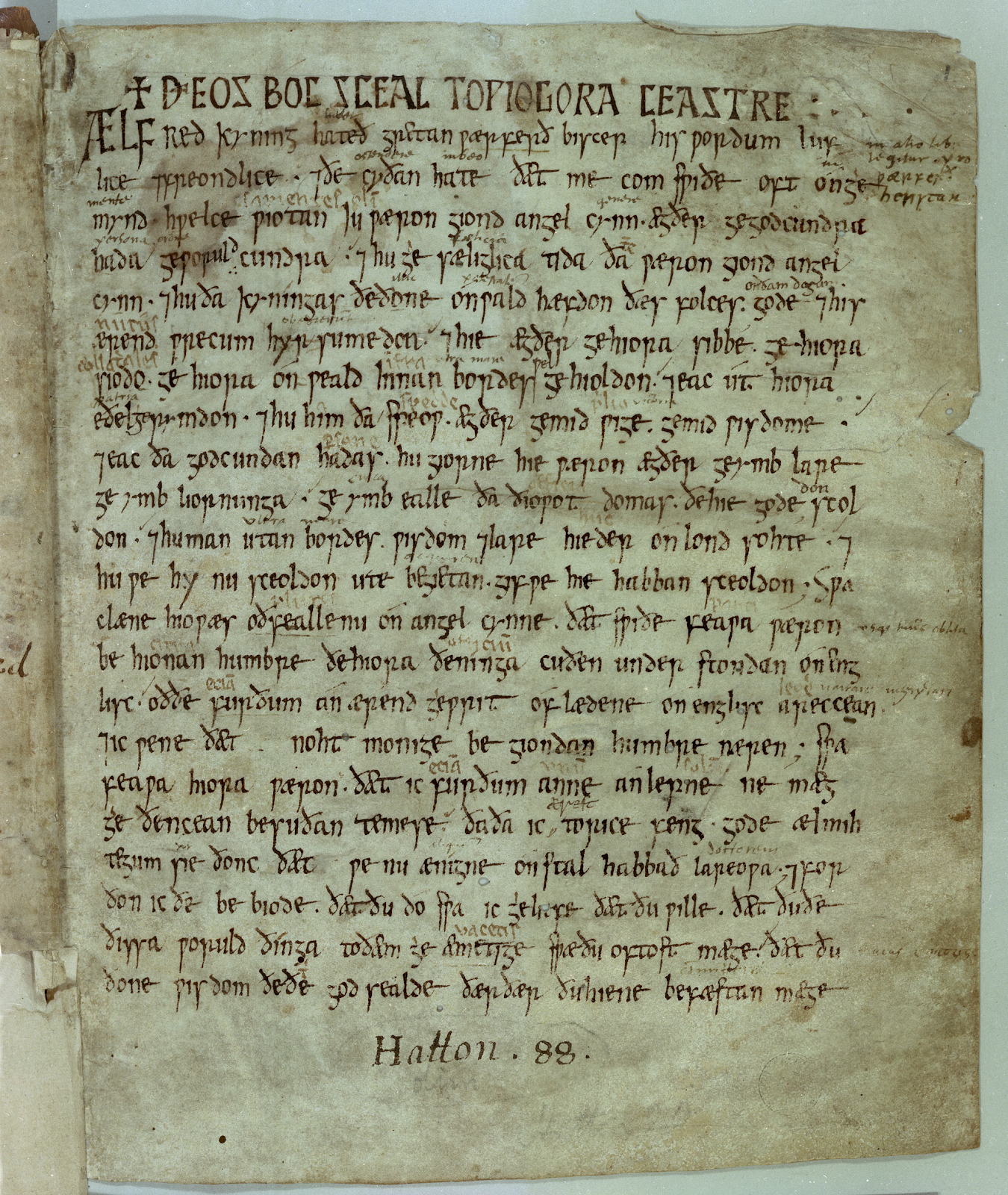

| Early medieval lay literacy in action: Alfred the Great's translation of Gregory the Great's pastoral care |

Before I finish with this post, we need to consider two things. Firstly, whether or not learning Latin was a barrier to literacy in the early middle ages. Secondly, whether it ever makes sense to speak of early medieval societies as oral cultures.

Tuesday, 14 February 2023

From the sources 13: Happy Valentines in Old French and Old High German

Happy Valentine’s Day everyone. Now I’m not going to write a

post about the history of Valentine’s Day itself, though I’d like to say that yes

it does have a medieval history but later than the kind of medieval I write

about here. A lot of very significant historical events happened on this day: the

Abbasid Revolution in Iraq in 748, the Papal Schism of 1130, the coronation of

Akbar as the ruler of the Mughal Empire in 1556, Captain Cook being killed by

Natives in Hawaii in 1779, Ruhollah Khomeini issuing a Fatwa against Salman

Rushdie in 1989 and the launching of YouTube in 2005, to name just six. But of

course, this blog bearing the name that it does, we’re going to be focusing on

an event in Carolingian history that happened on 14th February, in

the year 842 no less.

Ninth Century Frankish cavalry in the Golden Psalter of St Gall, nicely sets the tone for this

842 of course was in the middle of the Carolingian civil war

of 840 – 843, between the three sons of Emperor Louis the Pious. I’ve talked

about this a fair few times before, but at the root of it were the same forces that

meant that ninth century Carolingians could not have nice things – the failure

to equitably share power among the dynasty’s members, aristocratic factionalism

at court and opportunistic foreign powers (above all, the Vikings) deciding to get

involved. Lothar was trying to hold the empire together with his nephew Pippin

of Aquitaine, while his younger brothers Louis and Charles thought they deserved

their own piece of the pie.

By this point, it seemed like the civil war wasn’t going

great for Lothar, as in June 841 he and Pippin had suffered a catastrophic

defeat at Fontenoy. The next 8 months of the civil war saw very little actual

fighting. Instead, the rival Carolingian kings sent envoys between each other,

trying to negotiate a peace. They try and win over supporters from amongst the

Frankish nobles who were either trying to stay neutral, or were on the opposing

side. Meanwhile, opposing armies marched around the countryside of Northern France

and the Benelux countries, garrisoning citadels here, forcing enemy strongholds

to surrender there, blocking off routes where the enemy might approach

elsewhere, and so on. Contrary to what some people might think, battles weren’t

all important in ninth century warfare and were often indecisive. Indeed, its

revealing how our sources tell us so much about the campaigning side of

Carolingian warfare, yet provide us with barely any description of how the

battles were fought, instead focusing on their aftermath and consequences.

And there are a lot of sources for this section of

Carolingian history. Indeed, the 35-year period 828 to 863 is quite possibly

the best documented generation in Western political history between the fall of

the Roman Republic (66 – 31 BC let’s say) and the age of Richard the Lionheart,

John Lackland, Philip Augustus and Pope Innocent III (1188 – 1223). We know so

much about the intricacies of Carolingian politics at this time, and the full

range of partisan perspectives.

One of these sources is the historian Nithard (795 – 844).

Nithard is a very interesting chap, indeed quite a remarkable one. He was the illegitimate

son of Bertha, the third daughter of Charlemagne, and the court poet Angilbert.

I don’t want to go too much into this now, but Charlemagne seems to have

allowed his daughters an unusual degree of sexual freedom, which their brother

Louis the Pious thoroughly disapproved of. The emperor’s sisters were among the

first to be targeted in his attempt to “drain the swamp” at Aachen. Nithard

seems to have been educated at Charlemagne’s palace school at Aachen and thus

was thoroughly literate, proficient in the Latin language and very knowledgeable

of the ancient Roman Classics, especially the works of the historian Sallust

and the poet Lucan (both of whom wrote about civil war). He had of course also

learned how to ride, hunt, fight with weapons and conduct himself around court.

Indeed, one might say his education was fairly typical of a high-ranking

Carolingian aristocrat. Before the civil war, Nithard had been a courtier,

soldier and lay abbot of Saint Riquier.

Thus Nithard’s Histories provide us, along with the

works of Einhard, Angilbert, Eberhard of Friuli and Dhuoda, with valuable

insights into the attitudes of lay aristocrats in the Carolingian Empire and how

they saw the workings of politics. Nithard wrote his history as the events themselves

unfolded, and like Xenophon, Julius Caesar and Ammianus Marcellinus before him,

he wrote as a soldier and politician with first hand experience of it all. Of

course, as your average 16-year-old in a GCSE exam might say, crudely, that means

he’s “biased” – Nithard fought for Charles the Bald and portrays his king in a

positive light, and the enemy Lothar in a very negative one. Above all, he saw

the civil war as a tragedy tearing the Carolingian state (res publica in

the original Latin) apart and highly damaging to the welfare of the Frankish people,

yet kept faith that everything that unfolded was God’s judgement. Let us see

what he has to say about what went down on 14th February 842.

On the fourteenth of February Louis and Charles met in

the city which was once called Argentaria but is now commonly called

Strasbourg. There they swore the oaths recorded below; Louis in the Romance

language and Charles in the German. Before the oath one addressed the assembled

people in German and the other in Romance. Louis being the elder, spoke first …

The basic sum of what Charles and Louis says next is thus: Lothar

is an absolute rotter, and the civil war is all his fault. We’ve tried to offer

peace on the most reasonable terms, yet he refuses. But at least us two look

out for each other as siblings, so we’re going to swear these oaths to show you

what good loyal bros we are, and that we’ll work together to heal the body politic.

Nithard then records the oath Louis swore in front of

Charles the Bald’s soldiers in Romance thus:

Pro Deo amur et pro Christian poblo et nostro commun

salvament, d’ist di in avant, in quant Deus savir et podir me dunat, si

salvarai eo cist meon fradre Karlo et in aiudha et in cadhuna cosa, si cum om

per dreit son fradra salva dift, in o quid il mi atresi fazet et ab Ludher nul

plaid numquam prindrai, qui, meon vol, cist meon fradre Karle in damno sit.

The English translation goes thus:

For the love of God and our Christian people’s salvation

and our own, from this day on, as far as God grants knowledge and power to me,

I shall treat my brother with regard to aid and everything else a man should

rightfully treat his brother, on condition that he do the same to me. And I

shall not enter into any dealings with Lothar which might with my consent

injure this my brother Charles.

Charles then swore the same oath to Louis’ troops in Old High

German:

In Godes minna ind in thes christianes folches ind unser

bedhero gehaltnissi, fon thesemo dage frammordes, fram so mir Got geuuizci indi

mahd furgibit, so haldih thesan minan bruodher, soso man mit rehtu sinan bruher

scal, in thiu thaz er mig so sama duo, indi mit Ludheren in nohheiniu thing ne

gegango, the minan, uuillon, imo ce scadhen uuerdhen.

Then Charles’ soldiers swore this oath in their own Romance language:

Si Lodhuuigs sagrament que son fradre Karlo jurat

conservat et Karlus, meos sendra, de suo part non l’ostantit, si returnar non l’int

pois, ne io ne neuls cui eo returnar int pois, nulla aiudha contra Lodhuuuig

nun li iu er.

Which in English is:

If Louis swore the oath which he swore to his brother

Charles, and my Lord Charles does not keep it on his part, and if I am unable

to restrain him, I shall not give him any aid against Louis nor will anyone

whom I can keep from doing so.

Louis’ troops then did so in their own language:

Oba Karl then eid then er sinemo bruodher Ludhuuuige

gesuor geleistit, indi Ludhuuuig, min herro, then er imo gesuor forbrihchit, ob

ih inan es iruuenden ne mag, noh ih noh thero nonhhein, then ih es irruenden

mag, uuidhar Karle imo ce follusti ne uuirdhit.

In English:

If Charles swore the oath which he swore to his brother Louis,

and my Lord Louis does not keep it on his part, and if I am unable to restrain

him, I shall not give him any aid against Charles nor will anyone whom I can

keep from doing so.

The oaths as they appear in Nithard's histories

Besides political significance, what makes the oaths so

interesting is from the standpoint of written language. Here we are dealing

with some of the very earliest examples of written Continental European

vernaculars. In the case of what Nithard calls the “Roman” or “Romance”

language, which is very clearly Old French, the Oaths of Strasbourg as recorded

by Nithard are the very first text ever to have been written in that or any

other Romance language. In the case of Old High German, a few texts had been

written earlier in the Carolingian period, such as the Latin-Old High German

glossary called the Abrogans (c.770), or the Merseburg Charms (the

only surviving pre-Christian Germanic religious text). The oaths thus offer us lots

of insight into what these languages were like at this point in time, and how

they would later evolve.

As I’m not a philologist, I’ll keep the discussion of linguistics

brief. For the Old French you can very clearly see the languages’ Latin roots.

Some words are still in their Latin forms i.e. Deus (God), jurat (he

swore – historic present), conservat (he keeps), numquam (never)

and nulla (not any). But there’s clearly a lot of evolution i.e., amor

(love) in Latin has moved closer to the French amour with amur; avant

is recognisably the French word for before, as opposed to the Latin ante; and

sendra, soon to evolve into the Modern French seigneur (lord). auxilia

has evolved into aiudha, which is actually closer in spelling and

pronounciation to the Spanish than the French word for help; likewise, podir,

which has evolved from the Latin potere is cloiser to the Spanish poder

than the French pouvoir. The verb tenses also appear to be closer to

French i.e., for the conditional/ future words like salvarai and prindrai

have endings recognisably like how they would be in Modern French.

For the Old High German, I really can’t claim much expertise

– one term in year 7 is the only time I’ve ever formally studied any German, which

I know is problematic given how much important Carolingianist scholarship is written

in German. Still, you can see recognisable forms of German words in this text

i.e., folches (clearly related to volk – people), bruodher

(clearly related to bruder – brother), herro (clearly related to herr

– lord or master), dage (clearly related to tag – day) and Got

(God). And uuillon is clearly related to willa in Old English and

will in modern German and English.

Thus, the Oaths of Strasbourg are a moment of huge

historical significance in the history of Western European languages. Indeed,

from the Romance side of things, it basically marks the terminus ante quem

for when the Vulgar Latin dialects spoken in Gaul evolved into Old French –

when exactly one became the other is highly debated, but it was certainly before

842. Other Romance languages appear fully in written documents slightly later –

Italian is the next to come, in the 960s, followed by Spanish and Portuguese;

Romanian is the last, first appearing in 1521 (in Cyrillic letters, no less).

What was the attitude of the Carolingians to vernacular

languages. Well, its safe to say that in order to successfully navigate high

society in the ninth century Carolingian Empire, you had to be trilingual. Louis

the Pious had his sons Lothar, Pippin, Louis and Charles educated in Latin, Old

French and Old High German, of which the Oaths of Strasbourg are themselves

evidence, and pretty much all of the high nobility (the reiksaristokratie)

would have been educated the same, especially since many of them like Eberhard

of Friuli owned lots of estates in both Romance and Germanic speaking areas.

How much bilingualism, let alone trilingualism, spread down the social

hierarchy is much less certain. Charles and Louis’ soldiers, who we can

reasonably assume to have been drawn from amongst the middling landowners and

well-to-do free peasants, could only speak their native vernaculars, and so

said their oaths in them, unlike Charles and Louis who said their oaths in German

and Old French respectively so the other side’s troops would understand. At the

Council of Tours in 813, Charlemagne decreed that priests, depending on where

they were, should preach either in the Lingua Romana (Old French) or Theodisc

(Old High German) so the common folk could understand.

A ninetenth century artist imagines the scene of the Oaths of Strasbourg

As written vernaculars go, we have only one other example of

written Old French from the Carolingian era, a short late-ninth century poem on

the martyrdom of Saint Eulalia. After that, the next examples of written Old

French appear in the twelfth century with the birth of the chansons de geste

and other early chivalric fiction. For Old High German, there’s quite a bit

more from the Carolingian period. For example, the monk Otfrid of Wissembourg

(a monastery now in Alsace, France) produced the Evangelienbuch, an Old

High German verse translation of the Gospels, for King Louis of East Francia.

There are also some poems like Muspilli (a poem about Hell), the Hildebrandslied

(a fragmentary epic), the Georgslied (about St George) and the Ludwigslied

(about a Frankish victory over the Vikings). Still, the amount of Old High

German literature that survives pales in comparison to the amount of Old English

literature surviving from 685 to c.1100. Yet when you factor in the surviving

Latin literature, far more poems, treatises and histories survive from Carolingian

Francia in the ninth century than from the whole Anglo-Saxon period. Its

because they’ve got an unusually high proportion of vernacular texts, that

Anglo-Saxonists (or as some would now prefer to be called, Early MedievalEnglishists) are able to justify obsessively fixating on so few texts, to thepoint that Beowulf and the Battle of Maldon have been sucked dry and done todeath. Meanwhile, a great deal of medieval Germanist scholarship focuses on reconstructinghypothetical texts that may have never existed, rather than the Old High German

texts that are actually there. The Carolingians, however, had different priorities

to us and preferred Latin literature by far.

Saturday, 21 January 2023

William the Conqueror and Henry IV of Germany Part 1 – why compare them?

William the Conqueror and Henry IV of Germany Part 1 – why

compare them?

In this series of posts, I’m going to do something really

quite exciting and unconventional. I’m going to compare William the Conqueror

(1027 – 1087) and Henry IV of Germany (1050 – 1106). Why is this such a radical

idea? After all, both of these eleventh century rulers were each other’s contemporaries,

though William was of an older generation. Both rulers of course knew of each

other, which wouldn’t be true if I was attempting a comparison between William the

Conqueror and the Seljuk Turkish sultan Alp Arslan (d.1072) or between Henry IV

of Germany and the Song Chinese emperor Yingzong (r.1067 – 1085).

Indeed, both had quite strong reputations in each other’s

kingdoms, and chroniclers in each kingdom followed the other kingdom’s affairs

with great interest. William of Poitiers, the Conqueror’s chief propagandist,

claimed in 1075 that when William the Conqueror was planning his invasion of

England, he sent embassies to the court of King Henry IV to secure his support

as well as to the court of Pope Alexander II, though importantly not that of William’s

notional liege lord King Philip of France. Its of course unlikely that the

embassy happened, given that William of Poitiers, a highly articulate yet

unreliable narrative historian, is our only source for it. But the fact that

William of Poitiers would make the claim at all in a work intended to praise

the Conqueror to high heaven, indicates just how esteemed Emperor Henry IV was

in England and Normandy, as he was everywhere else in Western Christendom – the

German king-emperor was the most important monarch of them all. Likewise, from

the German side, Bruno of Magdeburg, writing in 1082, claimed that in 1074 when

King Henry IV was facing a full-scale rebellion against his rule in the duchy

of Saxony, he requested that William the Conqueror send military support. William

then curtly replied that he had claimed his kingdom by violent conquest, and

that if he left it alone for too long there would be rebellions. Bruno might

have simply been relying on gossip, but it does show (and we know this from

other German chroniclers too) that the Norman Conquest of England was much

talked about in Germany – perhaps Henry IV wanted to the Normans to harry his

own rebellious North.

Indeed, even if diplomacy was quite tenuous between England/

Normandy and the German Empire at this time, they would later be joined at the hip

when William the Conqueror’s granddaughter, Matilda (1102 – 1167), married

Henry IV’s son, Henry V (1086 – 1125). Some people easily look over this, but

Matilda did not have the title of empress for nothing, and she wasn’t happy

that for her second marriage she had to settle for a mere French count,

Geoffrey of Anjou. Had Henry V lived for 20 more years, then the “Anarchy”

would have taken a much more interesting turn with Swabian and Bavarian knights

causing mayhem in the Home Counties and the Midlands. Perhaps we would have had

German kings of England five and half centuries before we actually did, the

Hundred Years’ War would have been completely avoided and Shakespeare would

have written plays about kings called Otto and Conrad as well as, of course,

Henry.

Perhaps most importantly of all, both rulers are remembered

as highly significant in their respective countries. Their reigns are seen as turning

points, indeed the pivotal moment, in English and German medieval history

respectively – everything before them is inevitably seen in their shadow, and

everything afterwards flows from them. What the Battle of Hastings in 1066 is

to the English, Henry IV’s penance at Canossa in 1077 is to the Germans – they’re

the dates that every schoolchild knows (or at least is supposed to know) and

which you should never set your credit card PIN number to. If you ask the

average educated English person to name five memorable medieval kings, William the

Conqueror will almost certainly be one of them, and if you said the same to the

average educated German, they’d probably name Henry IV. And the period they

lived in was one of genuine cataclysmic change in both of their countries,

which was driven by many of the same forces – the rise of knights, the

proliferation of castles, a whole umbrella of economic and social changes and

of course the growing power and authority of the papacy. So why have they

normally been studied in isolation from each other?

You see, medieval political history has traditionally been written on national lines. English historians of medieval politics focus on England, German historians of medieval politics on Germany, French historians on France and so on. From the nineteenth century through to after WW2 this was very much the established way of doing things, though since the 1970s that has changed. Notably though, there are a lot more British and American historians of medieval Germany than there are German historians of medieval England. Nonetheless, this still means there’s traditionally been the presumption that Medieval English and medieval German history have very little to do with each other.

Still, national traditions

of scholarship leave a long shadow. As a result, until a few generations ago historical scholarship on Medieval English politics was shaped by the question that preoccupied the Victorians: why did

a powerful and centralised national monarchy that gave birth to the common law,

Parliament and ultimately Great Britain and the British Empire emerge.

Meanwhile, German historians, like their predecessors in the Imperial and

Weimar eras, still return to the opposite question: why did the German emperors

increasingly lose control so that Germany ended up a loose confederation of

squabbling principalities, suffered the tragedies of the Thirty Years’ War and

Napoleonic occupation and was only unified in 1871 by the iron will of

Bismarck. The Norman Conquest and the Penance of Canossa respectively

have traditionally been identified as key turning points for both.

What makes all of these traditional scholarly preoccupations important is that English historians have since the nineteenth century traditionally focused on the state, the law, bureaucracies, court cases and constitutional matters, and many still do. Since the 1950s and even more so since 1990, however, there has been a widespread interest among political historians of early and high medieval England in the social side of politics. There’s been a lot of work on lordship (personal power over people of lesser status), patronage networks, family relationships, aristocratic identity and stuff like that.

On the German side of things, historians increasingly from the 1920s onwards and overwhelmingly so since the end of WW2, have generally ignored the study of medieval government and administration (the Verfassungsgeschichte that was much more fashionable in the Imperial period) in favour of a way of looking at medieval politics that focuses on the personal relationships between the king/ emperor and the political community – ties of lordship, patronage, family and friendship. A successful medieval king wasn’t one who issued laws that dictated how things were to be run across the country, taxed his subjects rigorously, punished criminals with harsh justice and generally worked to increase the power of the central government and the bureaucracy against the nobility and other vested local interests. Rather, as German medievalists have tended to see it, a successful medieval king was one who worked hard to get all the nobles on the same page as him and be on as friendly terms with them as possible, play by the time-honoured “rules of the game” (to use Gerd Althoff’s phrase) of kingship and generally act like the just and gracious lord of his people. Kings who succeeded in all this could then achieve lots of stuff by bring the nobility of the kingdom/ empire together in royal assemblies and armies. German historiography also stresses the importance of ritual and symbolic actions in how this consensus was built up between kings and aristocrats, such as displays of anger, the shedding of tears, kneeling or prostrating oneself to ask for forgiveness, bringing in holy relics to court gatherings or army musters, seating plans at assemblies and feasts and the like. And yet people talk about "gesture politics" like its a new thing!

What this means is that, in more than just a literal sense,

English and German historians speak a very different language when it comes to

discussing medieval politics. As a result, it seems like the two political systems

of England and Germany in the middle ages were profoundly different and cannot

be understood in each other’s terms, making any kind of meaningful comparison

impossible. And on the surface of it, its easy to see this as just a natural

state of affairs because the actual content they work on is very different. Lets

turn to the two rulers we’re comparing. William the Conqueror was able to defeat

and kill a rival contender for the throne, Harold Godwinson, in one decisive

battle on 14 October 1066, and just over two months later he had seized control

of the effective capital of England (London) and with it the machinery of government

and was crowned king. Then over the next five years, he was able to completely subdue

the whole country by force and replace the majority of its ruling class with

foreigners loyal to him. By contrast, Henry IV faced betrayals, rebellions and

civil war for almost all his reign and temporarily lost all authority over his

kingdom when in 1076 the Pope released his subjects from their oaths of loyalty

to him. This he could only regain if he approached the pope as a humble

penitent begging for forgiveness. The sources are also hugely different. For

example the most famous document from Norman England is of course the Domesday Book – a government

survey of (almost) his entire kingdom that records land ownership, economic

activities, wealth, tax assessment and the (adult male) population. Likewise there are lots of writs and charters and other administrative records surviving from Norman England. There are plenty of detailed narrative histories for the Anglo-Norman period - Orderic Vitalis, William of Malmesbury, Henry of Huntingdon - but they're counterbalanced by these administrative records. Meanwhile,

Henry IV’s Germany is very different. While poor in administrative records it is rich in chronicles, many

of them written by historians hostile to Henry IV like Bruno of Merseburg and

Lamprecht of Hersfeld. These provide lots of "thick description" of rituals, assemblies and battles, but have little to say about the workings of government. Thus, in contrast to the Anglo-Norman case, they do so much more to colour how historians view the workings of politics in the period.

Thankfully, over the last fifty years, some historians,

almost all of them English and most of them specialising in Continental European

medieval history (though also including some intrepid and outgoing

Anglo-Saxonists) have tried hard to bridge the scholarly great divide and challenge

the insularity and historiographical navel-gazing of English and German

medievalists alike. To give a short list of them (in chronological order) they

include Karl Leyser, Timothy Reuter, Janet Nelson, Sarah Foot, Catherine Cubitt,

Simon MacLean, Charles Insley and Levi Roach. There’s been a lot of work

recently on the importance of just the kind of ritual and symbolic communication

stuff that German medievalists like Gerd Althoff focus on, in relation to late Anglo-Saxon

England, though Anglo-Normanists have been slower to follow up on this trend. Indeed

its frankly bizarre that its taken so long for English medievalists to see the

importance of demonstrative behaviour and symbolism in medieval kingship. After

all one of the most famous episodes in English medieval history opens with a

king throwing a tantrum and ends with the same king making a humble pilgrimage to

Canterbury and being whipped bloody by monks to apologise to the archbishop

whose death resulted from his anger. The whole saga of Henry II and Thomas

Becket makes a great deal more sense if you have in mind Henry IV at Canossa in

1077, or from an even earlier time Emperor Otto III in 1000 making a pilgrimage

to Gniezno to visit the tomb of the martyred Adalbert of Prague and greeting Duke

Boleslaw the Brave of Poland in the humble garb of a penitent. And

Anglo-Normanists have tried to look at the Norman Conquest in a more pan-European

perspective as well, as exemplified by work from people like David Bates,

Robert Bartlett, Stephen Baxter and (again) Levi Roach.

|

| Canterbury 1174, when even the most old school historians finally realise that the politics of Norman and Angevin England weren't a ritual free-zone after all |

But enough of the historiographical detour. In my view,

William the Conqueror and Henry IV, while they mostly don’t match up,

nonetheless make a really stimulating comparison for thinking about how

eleventh century kingship worked (both through similarities and differences),

the momentous changes going on all over Europe and how events almost a thousand

years ago can still be so resonant and controversial today. In subsequent posts

we’ll be exploring both rulers’ childhoods, how they presented themselves as rulers

and faced challenges to their authority and how their reigns were shaped by

broader forces of change.

Sources cited

Primary

William of Poitiers, The Gesta Guillelmi, edited and

translated by Marjorie Chibnall, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1998)

Secondary

Gerd Althoff, Family, Friends and Followers: Political

and Social Bonds in Early Medieval Europe, 500 – 1200, translated by

Christopher Carroll, Cambridge University Press (2009)

Elisabeth Van Houts, ‘The Norman Conquest through European

eyes’, English Historical Review 110 (1995)

Charles Insley, “‘Ottonians with pipe rolls?’ Political culture

and performance in the kingdom of the English, c.900 – 1050’”, History 102

(2017)

Why this book needs to be written part 1

Reason One: the Carolingian achievement is a compelling historical problem This one needs a little unpacking. Put it simply, in the eighth c...

-

All Hitler and Henry VIII? Some insider reflections on what history actually is taught in UK schoolsPlease note: while I'm not exactly the Scarlet Pimpernel, Zorro, Superman, Spiderman or Batman, I do have a kind of dual identity thing....

-

I can’t tell you how great it feels to be writing a blogpost now. The last two weeks have been absolutely hectic for me with the PGCE and ...

-

A much later (early fourteenth century?) satirical image of a medieval schoolroom featuring monkeys! So when we last left Guibert, he was ...