Please note: while I'm not exactly the Scarlet Pimpernel, Zorro, Superman, Spiderman or Batman, I do have a kind of dual identity thing. There's trainee secondary school teacher me and there's freelance early medieval historian (more accurately, unpaid blogger and unapologetic Carolingian fanboy) me. Normally I try to keep the two apart, but this time I thought I'd do something a little different.

If you’ve lived in the UK in the last twenty years, you’ve

probably heard somewhere that all secondary schoolchildren learn about in history

these days are Tudors and Nazis. You hear it from politicians, journalists,

public intellectuals, people concerned with the state of education in the

twenty-first century UK and people slightly miffed that their favourite

historical period doesn’t generate the interest it deserves. Whether they’re

scandalised that schoolchildren these days can’t tell apart their Nelson from

their Wellington, or that the Tolpuddle Martyrs and the Amritsar Massacre don’t

appear enough in the textbooks, the agreement is clear. It really is the one

thing that can unite Tory Brexiteers with ex-Corbynites and the Black Lives

Matter movement. Is it really so?

The short answer is, of course, no. The first reason is a

lot of media commentators either don’t seem to grasp, or maliciously obscure,

the distinction between the different levels of the UK secondary school system

– Key Stage 3 (11 – 14 years old), Key Stage 4/ GCSE (14 – 16 years old) and

Key Stage 5/ A Level (16 – 18 years old). Now if any school history department

taught only sixteenth century England and twentieth century Germany at Key

Stage 3, it would fail inspection by OFSTED (the government regulatory body for

English schools). Likewise, none of the GCSE or Level exam boards allow any

history candidates to only be examined on the Tudors and the Nazis. So, in sum,

the proposition is absurd and symptomatic of either ignorance or malice.

Enough smug dismissal! Like all myths and misconceptions,

the idea that the only history teenagers learn in school these days is the

Tudors and the Third Reich doesn’t appear in a vacuum either. But first, we

must demystify for those of you don’t have insider perspectives, how the history

curriculum for 11 – 18 year olds actually works in the UK.

From the ages of 11 – 14 (what is officially known as Key

Stage 3), history teaching is governed by the National Curriculum set by the Department

of Education. However, currently 88% of secondary schools in the UK are either central

government-funded academies, free schools or private schools, which are under

no legal obligation to follow the National Curriculum. Only local authority-funded

schools, faith schools and (academically selective but state-funded) grammar

schools have to follow the National Curriculum, which are now less than 12% of

schools in England. There is a certain level of irony in all of this. The

former education secretary Michael Gove fought a four year battle with the teaching

unions (“the blob” as he unflatteringly called them), the vast majority of academic

historians in the UK and the civil service to radically overhaul the history

curriculum. As you would expect, the rhetoric of “it’s all Tudors and Nazis”

these days was invoked by Gove and his supporters. Take for example Gove’s

speech at the Conservative Party Conference in October 2010:

“Children are growing up ignorant of one of the most

inspiring stories I know — the history of our United Kingdom. Our history has

moments of pride, and shame, but unless we fully understand the struggles of

the past we will not properly value the liberties of the present. The current

approach we have to history denies children the opportunity to hear our island

story. Children are given a mix of topics at primary, a cursory run through

Henry VIII and Hitler at secondary and many give up the subject at 14, without

knowing how the vivid episodes of our past become a connected narrative. Well,

this trashing of our past has to stop.”

Gove’s masterplan was to combine Primary Key Stage 2 (7 – 11

years old) and Early Secondary Key Stage 3 (11 – 14 years old) into a single

linear seven year course covering the full-sweep of English history. Primary

schoolchildren would have to learn about everything from the beginning of the

Stone Age in 10,000 BC to the Act of Union in 1707, and Secondary

schoolchildren everything from the creation of Great Britain in 1707 to the

Fall of Thatcher in 1990. The whole idea was completely bonkers, not least

because primary school history is taught overwhelmingly by non-subject specialists

(many primary school teachers may not even have a GCSE in history) on a highly

squeezed timetable where literacy and numeracy are always the biggest

priorities. Thankfully, Gove lost the battle and the new National Curriculum published

in 2013 was really little different to what which Ed Balls had introduced in

2008 under New Labour. What makes this all ironic is that another education

policy of the 2010 – 2015 Coalition was to encourage local authority-funded

schools to become academies – schools that failed OFSTED inspection would be

forced to become them. Between May 2010 and September 2012, the number of academies

went up tenfold so that on 7 September 2012 54% of state-funded secondary schools

were either academies or in the pipeline to become them. Ten years later, that

figure (including free schools, another Coalition government initiative) would

stand at 80%. So, one could be cynical and say that really the political battle

over the National Curriculum for history was all “sound and fury, signifying nothing”,

given that as a result of the same government’s policies most secondary schools

were now no longer under any obligation to teach it.

Yet actually, the National Curriculum for Key Stage 3 does still

have a fair amount of consequence on the majority of UK secondary schools. That’s

because it serves as a highly useful guideline, especially for making sure all

your students have reached where they need to be in terms of knowledge and

skills in all their subjects before they start their GCSEs. Thus only a small

minority of radical and experimental schools will teach anything that

fundamentally deviates from the National Curriculum – this is true even of

private schools.

And for history, the National Curriculum offers a huge level

of freedom in itself. You do have to teach Key Stage 3 pupils the fundamental

historical skills and second order concepts like causation, change and

continuity, evidence and enquiry, interpretation and significance. You also

have to teach them a range of cross-period first order concepts like

architecture, church, dictatorship, empire, hierarchy, peasantry, suffrage etc.

In terms of what actual historical content you have to teach, however, it works

thus:

·

A broad overview of British history from 1066 to

1945, including how government, society and culture in England have changed

over time. Schools can however choose which key people, periods and events

within that rubric they study in depth and which ones they cover superficially,

if at all. The topics most commonly taught in English schools are:

1. The

Norman Conquest

2. The

feudal system

3. Henry

II and Thomas Becket

4. King

John and the Magna Carta

5. Medieval

life – religion and the church, villages, towns, women, crime and justice

6. The

Black Death

7. The

Peasants’ Revolt

8. Henry

VIII and the Reformation

9. Elizabeth

I and the Spanish Armada

10. James

I and the Gunpowder Plot

11. Charles

I, the Civil War and Cromwell

12. Other

developments in Tudor and Stuart England – could include the Renaissance, the

age of exploration, growing wealth and poverty, the witch craze, black people

in Tudor England, the seventeenth century scientific revolution.

13. The

Industrial Revolution

14. The

British Empire

15. Victorian

change – could include Chartism and the rise of democracy, Darwin’s “The Origin

of Species”, the Great Exhibition, public health and social reform, urbanisation,

policing and Jack the Ripper etc

16. The

Suffragettes

17. Britain

in WW1

18. Britain

in WW2

·

The Transatlantic Slave Trade and Abolition

·

Hitler and the Holocaust

·

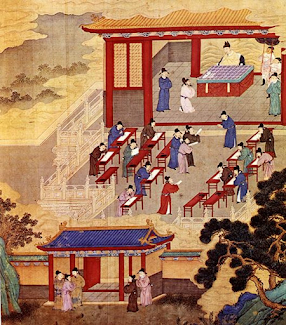

At least one period of international history

other than the two mentioned above. The National Curriculum gives as examples Mughal

India 1526 – 1857, Qing China 1644 – 1911, changing Russian empires c.1800 –

1992 or the twentieth century USA. The medieval Islamic world, African kingdoms

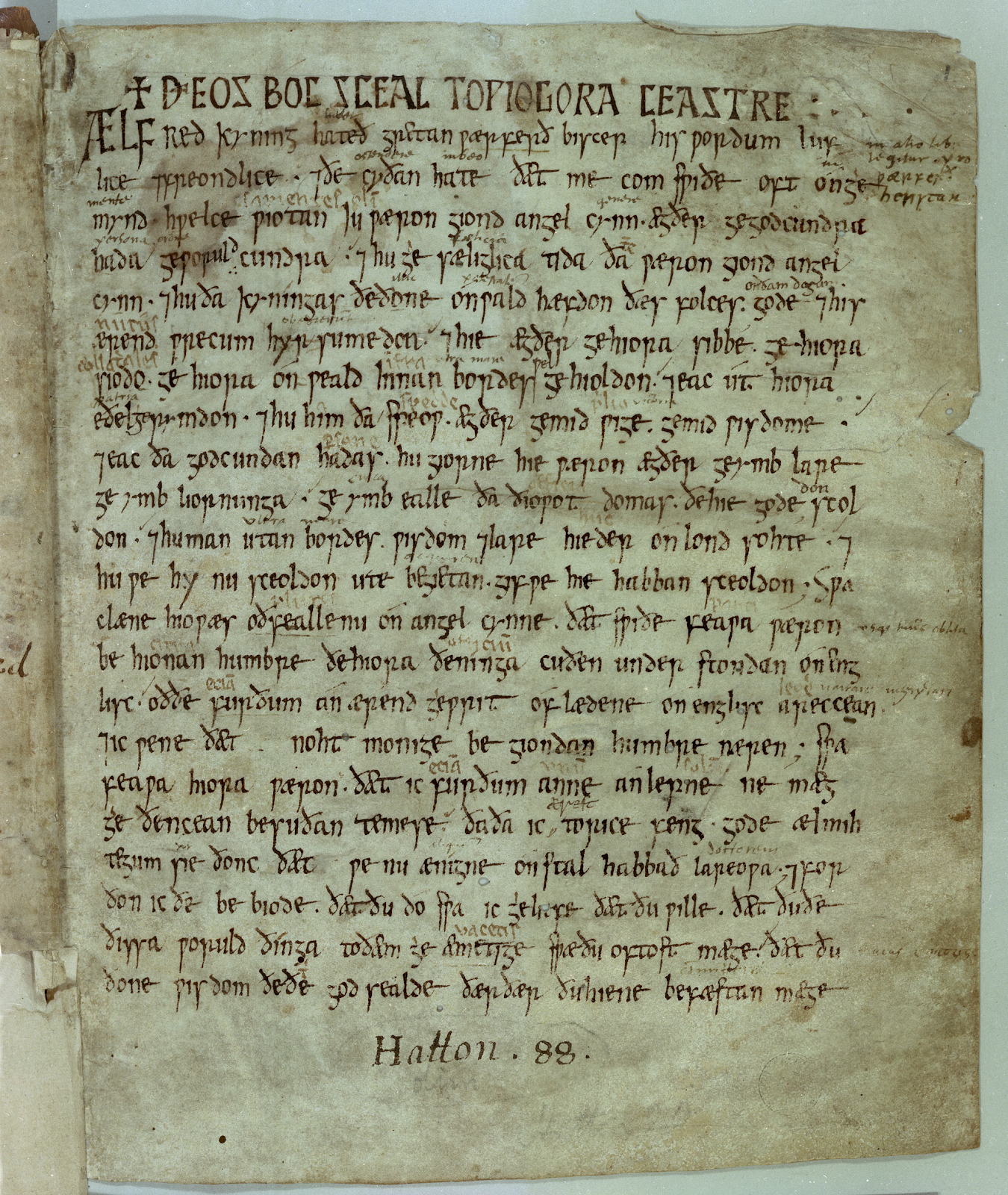

and Native Americans are also becoming increasingly popular.

·

Some aspects of British history from before 1066

·

A local history enquiry

So essentially the National Curriculum for history at Key

Stage 3 is like a buffet where you have to include a few specific foods on your

plate and have to make sure the amount of food you pile onto it doesn’t spill

over. It’s not tightly prescriptive at all. Indeed, there’s arguably a small

element of longue duree (got to admit, I dislike that trademark phrase of Fernand

Braudel) in all of this, as until 1988 there was no mandatory national

curriculum in history at all, so schools could in theory teach any history they

liked but in practice mostly taught British history in chronological order.

Many people are dissatisfied with this status quo. The conservative

right, for one. While the current national curriculum was passed under the Tory-led

government of David Cameron, it was only passed in that version because Michael

Gove had to backdown from his original plan for nothing short of world

domination in the face of overwhelming opposition. Right wing politicians, journalists

and historians are always complaining that children can easily go through their

entire school careers without learning anything about Simon de Montfort and the

emergence of parliament, the battle of Agincourt, the Glorious Revolution, the

Seven Years’ War, the battle of Trafalgar or Gladstone and Disraeli. In their

view, too little serious historical content is taught in favour of soft

historical skills, and the glories of the British (implicitly English) past are

done down, trashed and ignored.

Meanwhile, left-wingers also find the curriculum wanting.

They see the history curriculum as still being too focused on high politics and

rich white men, and that the struggles of ordinary working people for basic rights

and freedoms, women’s history, Black and Asian British history and increasingly

LGBT history as well should be given more attention. The toppling of Edward

Colston’s statue in June 2020 in the wake of the killing of George Floyd and

the Black Lives Matter movement has led to an increased demand for more

imperial history to be taught in schools. Many academic historians have, for a

long time, felt that the history taught in English schools is too parochial and

Anglocentric. The climate crisis is creating a demand for ecological and planetary

history to be taught – should lessons on the industrial revolution now include

the question of why we live in the Anthropocene? The history curriculum is as

much of an ideological battleground as ever.

In spite of all this, I actually think the national

curriculum as it stands, for all its shortcomings, is really the least worst option

we have. I think inevitably its going to have to inevitably be mostly British

history we teach at Key Stage 3. While I’d personally love to teach more

international history, not least because British history is always better

understood in a wider European and global context, national history is always

going to make up more than half of what’s taught. There’s a strong belief that children

should be taught about the environment they know best, that being their own

country or local area, and some would argue that teaching too much non-British

history could be alienating to white working-class students. It’s also a widely

held view that education should have a civic purpose – these kids are future

voters, they need to understand the country they’re living, its political

system and how they came to be that way so they can make good decisions at the

ballot box, or indeed bother to turn up there. Conservatives and nationalists would

also consider it unpatriotic and scandalous if mostly non-British history was

taught in schools. But even if British history inevitably wins pride of place

on the curriculum, that doesn’t remove the imperative for schools to try their

best to tell diverse stories within that rubric. A lot of schools are already

making a good effort to teach more black British history, and figures like John

Blanke and Walter Tull are soon to become household names. British women’s

history, however, noticeably lags behind. For many schoolchildren, the only

named historical women they’ll encounter in any depth during their Key Stage 3

curriculum are sixteenth century queens (with the exception of Elizabeth I,

mostly viewed as wives and mothers), the victims of a Victorian serial killer and

the suffragettes. Some schools, however, are trying to break this mould, and to

a medievalist like myself it does look like progress to see Empress Matilda and

Eleanor of Aquitaine appearing as topics for year 7s studying medieval England.

It could be even richer if Licoricia of Winchester (I have yet to encounter

schools that teach about the Jews in medieval England), Julian of Norwich and

Margaret Paston were to follow, all of whom could make very stimulating Key

Stage 3 enquiries for getting students to think about historical significance

and evidence.

But there is still plenty of scope for schools to bring in world

history and there are some absolutely fabulous curricula out there. For

example, at my first placement school, they had on their Key Stage 3 curriculum

map Ming China 1368 – 1644, Islamic Empires 600 – 1200, Mughal India 1526 – 1760,

the French and Haitian Revolutions 1789 – 1804 and the Partition of India in

1947 as well as more conventional topics like the Normans, Tudors, Stuarts, Industrial

Revolution and World Wars. And at the school I attended for sixth form (16 – 18

years old), their new year 7 curriculum (11 – 12 years old) includes the

Byzantine Empire, the Rise of Islam, Kievan Rus, Genghis Khan, Mansa Musa,

Tamerlane and more – they’ve even got Charlemagne on there (my absolute

favourite topic, as you know!). And in the late spring and summer term at my

current placement school, I will be teaching Islamic Civilisations 600 – 1600

to the year 7s.

I think it always works best if its driven somewhat by interests

of the school’s history department. There are lots of absolutely brilliant secondary

school history departments where the teachers are incredibly passionate about

their subject (they may have master’s degrees in history, or even further

academic qualifications) and are constantly trying to build their historical knowledge

and understanding of all kinds of different periods by reading up to date

historical scholarship whenever they can afford the time. Departments like these

are able to design truly cutting-edge curricula for their schools that still go

broadly in line with the National Curriculum but above and beyond it, introduce

students to a range of different countries in different periods and build enquiry

questions into these topics for their pupils to explore that reflect current

scholarly debates. By contrast, many history departments are full of ordinary, run

of the mill history teachers who, already overwhelmed by the obscene workload

combined with home and family life, just can’t find the time and motivation to

develop their subject knowledge and therefore just want to stick with the

topics they already know and for which there’s already decades worth of

teaching and learning resources on. It’s also important cultural backgrounds of

their pupils are taken into consideration. If you’re teaching in a school in a

highly diverse borough of London, Birmingham, Manchester etc where the majority

of students are of Afro-Caribbean or South Asian heritage then its absolutely

imperative that your students are able to learn more about their heritages in

the school curriculum and see people who look like them represented in the

curriculum. By contrast, if you’re teaching in a school in rural Devon, Lincolnshire

or Cumbria, where 98% of your students are White British, then topics like Mali

or the Mughals taking up as much space as the Tudors and Stuarts will go down

less well. At the same time, lets not make too many assumptions and make too

many arguments about identity. I’ve taught at a school where the majority of

students were of South Asian heritage, and many of them were incredibly

enthusiastic for learning about the Anglo-Saxons, Vikings and Normans. And who’s

to say white students can’t get excited learning about African and Asian

history. Coming at it from a different angle, would it be at all right to suggest

that the suffragettes shouldn’t be taught in all boys’ schools? At the end of

the day, history is all about exploring people, places and periods different to

what we are familiar with, and also identifying the broader commonalities in

the human experience across time and space.

We must never lose sight of one very important fact – that history’s

place on the school timetable is incredibly squeezed. The biggest priorities

for curriculum time in all schools are English, Maths and Science, since they are

the subjects all students will have to sit at GCSE and are widely seen as most

fundamental to students being able to get good jobs when they’re adults. Many

schools now make modern foreign languages compulsory at GCSE as well, so they

get greater priority too. Many private and grammar schools will also have

compulsory Latin at Key Stage 3 as well. History then has to vie for the

remaining curriculum time with geography, religious studies, art, design and

technology, IT, music, sports and PSHE (what is elsewhere called citizenship or

social studies). Given that kids are at school 5 days a week for approximately

7 hours (many grammar and private schools have somewhat longer timetables),

including breaktimes, lunchtimes and tutor time/ school assemblies, history can

only be given at most two hours a week on the school timetable at Key Stage 3, and

sometimes half as much. That means there is immense time pressure on the

curriculum, especially since teachers need to build students historical skills

and literacy as well as their knowledge of what happened in the past. Thus, any

school history curriculum has to be incredibly selective in what it teaches.

This is what both the right-wing and left-wing critics of the curriculum miss. It

simply isn’t possible to teach kids about every great British victory or every

colonial atrocity except in a very superficial manner. The right really ought

to know that the kind of history curriculum they want has already been tried,

and the result was “1066 and all that.” The left ought to have the foresight to

know that if they had their way, the result would be much the same all except “1919

and all that.” Its much better, in my opinion, that a smaller range of people

and events be studied in depth, along with creating a broader understanding of

the key features of the period they belong to. For example, studying a pair or

trio of sufficiently contrasting medieval kings (i.e., Edward I with Edward II,

Henry V with Henry VI etc) works better than trying to fit in all the

Plantagenets. Likewise, studying the impact of British rule on a particular

colony i.e., Jamaica, Australia, India or Zimbabwe makes a lot more sense than

trying to do justice to the whole empire in all its vastness and diversity. Its

these depth studies that actually bring them anywhere close to what historians

actually do. At the end of the day, we have to ask ourselves, are we teaching

our kids history, or just how to be really good at pub quizzes?

Then there’s raw politics. If the content of the curriculum

were to be more tightly controlled and prescribed by Westminster and Whitehall,

then there would be a definite ideological slant to school, history and left or

right, depending on which one was not in government, would be up in arms. Then

as soon as Labour or the Tories would be out of office, the party now in

government would want the curriculum changed to fit their vision of the British

past, which would create further indignation and more agonising workload for

teachers. It should really be a source of national pride for us in Britain,

that we have never had such a thing as government issued history textbooks, as

do exist in countries like Japan and South Korea. Let us pray that remains the

case for the foreseeable future.

I’m not going to get on to the issue of GCSE and A Level

history here. As all of my UK readers will know, history is not compulsory for schoolchildren

after they reach the age of 14, nor has it ever been. This makes the UK highly

unusual among OECD countries, and many see this as a situation that needs to

change. I must say that, as a trainee history teacher, I would never support a

compulsory history GCSE – its logistically impossible at the moment and would

only lead to dilution, dumbing down and disaffection. But fortunately for me in

terms of job prospects, history is a very popular subject at GCSE – about 47%

of 14-year-olds in England choose to do it now, more than ever before. Anyone who

says that history is dying in schools is just being alarmist for the sake of it.

But what that does mean is that the other 53% of schoolchildren will not formally

study any history past the age of 14, making the kind of history they learn at

Key Stage 3 all the more critical for them going forward as adult citizens. Thus

the Key Stage 3 history curriculum will always have to remain a political battleground

for the foreseeable future and there’s nothing we can do about it. But, for all

its shortcomings at the moment, it’s a good deal more sophisticated than just

Hitler and Henry VIII.