|

Now this is every bit what you expect a Once and Future King to look like: A colourful Flemish tapestry woven c.1400 (now in the Cloisters Museum, New York City) depicts King Arthur enthroned under a sumptuous Gothic architectural canopy. Royal magnificence really has been dialled to the appropriate maximum here.

|

|

| Imperial Arthur? A miniature of King Arthur from a manuscript containing multiple historical works, including Pierre Langtoft's chronicle, produced in Northern England sometime between 1307 and 1327, now in the British Library. Arthur is depicted in the armour typical of the first quarter of the fourteenth century (mostly mail but with plate vambraces on his elbows, poleyns on his knees, greaves on his lower legs and sabatons on his feet). He is armed with a lance and has his sword Excalibur at his belt, and so he is equipped with all the weapons befitting of a knight. On his left arm is a shield with an image of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child emblazoned on it (interestingly, in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Gawain's shield is similarly decorated but on the reverse side), which symbolises that he is a pious man, that he trusts the Lord Jesus Christ and the Blessed Virgin to protect him in battle and that he is willing to shed blood in defence of the Christian faith - as any good knight damn well should be! Below him in the box is a list of thirty kingdoms subject to Arthur's rule. Among them are, besides England and Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Norway, Denmark, France, Germany, Aragon, Castile, Portugal, the city of Rome itself and even Egypt and Iraq. Such an image of Arthur mattered a lot to people in late medieval England - it gave English history a great conquering hero to rival Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar and Charlemagne, someone to take great pride in. There's a great irony in a figure originally intended as a Welsh hero fighting against invading Anglo-Saxons becoming an icon of English nationalism. Its doubly ironic in how the figure of Arthur was used by thirteenth and fourteenth century Englishmen to justify the subjection of Scotland, Wales and Ireland to England, as the great historian Sir Robert Rees-Davies pointed out in the introductory chapter to The First English Empire: Power and Identity in the British Isles 1093 - 1343 (2000). This manuscript was itself produced in the reign of Edward II, when Plantagenet imperialism had succeeded in Wales but was failing in Scotland. |

|

| A "historical" King Arthur on the big screen? Clive Owen and Keira Knightley as Arthur and Guinevere in "King Arthur" (2004). Arthur is reimagined as Lucius Artorius Castus, a fifth century AD Roman cavalry officer, his knights as Sarmatian auxiliaries and Guinevere as a Celtic warrior woman. Whether it actually lived up to its claims to be a more "historical" take on the legend is questionable, to say the very least, as we'll soon see. |

So here we are. The blog has now surpassed seven months, making it more than half a year old, and, following some reflection, I've decided to shift the balance a bit away from educational posts and a bit more towards giving my own takes on some of the million pound questions of early medieval history. I think I might also do some posts in which I give my thoughts and theories on questions of a more general historical nature and what the purpose of early medieval history is in the present day. I thought we'd start off with something that links to a previous monster-post of mine and which touches on a subject that's always been of much personal importance to me - King Arthur.

I guess I've always been interested in King Arthur. I guess it came naturally from being interested in knights and castles as a kid, which was more or less the foundation stone of all my subsequent love of history. I listened to lots of stories and read lots of picture books about Arthur and his knights of the Round Table, pretended to be them in imaginative games and enjoyed watching movies like "The Sword in the Stone" (1963) and "Quest for Camelot" (1998). Later on, me and pretty much all of my family, friends and acquaintances would hugely enjoy watching the BBC Television series "Merlin" (2008 - 2013). For those not familiar with it, "Merlin" is an absolutely brilliant reimagining of the traditional Arthurian legend - Arthur becomes an arrogant, bumbling Bertie Wooster-ish figure while his butler Merlin (the Jeeves to his Wooster) saves Camelot time and again from the forces of evil without Arthur knowing. When I got hooked on ancient Rome in years 3 - 6 (7 - 11 years old) at primary school, I began to get in the possibility of a historical King Arthur. We covered the fall of Roman Britain in year 3 (the same year I went dressed as a Saxon invader with a proper seax on World Book Day), in which the existence of King Arthur, as a Romano-British warlord rather than as a medieval king, was presented as fact. Subsequently, I watched "Last Legion" (2008) and my mum read to me "The Lantern Bearers" (1959) by Rosemary Sutcliffe, both of which go into that territory. Closely linked to that was my growing fascination with the late Roman army and the fall of Rome, which I loved reading about in my various children's history books about ancient Rome. And at the age of 12 I fell in love with "Monty Python and the Holy Grail", in which the Arthurian stories of my earlier childhood were subverted and parodied with the Pythons' trademark irreverent and surreal humour. Indeed, to really nail my colours to the mast, I would say that any medievalist worth their salt should have heard of and enjoyed Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

|

| "You fight with the strength of many men Sir Knight ... Will you join me ... You make me sad, so be it! Come Patsy!" The Black Knight sequence is one of my favourite bits from that 1975 classic, and its actually a remarkably accurate illustration of chivalry as a twelfth century knight would have understood it. Arthur recognises that the Black Knight, who has just slain the Green Knight in single combat, has its central tenet (prowess) in spades, and so invites him to join his knights at Camelot. The Black Knight, however, sees an opportunity to further demonstrate his prowess by challenging this armed stranger to an honourable roadside duel, something which we know some twelfth century knights actually did. |

Thus, to summarise, throughout my life I've had a deep fascination with both of the two Arthurs - on the one hand the historical Romano-British warlord who fought back against the Saxon invaders; and on the other, the mythical once and future king and paragon of chivalry. In a way, he represents the link between my two childhood fascinations that got me into history - ancient Rome, on the one hand, and medieval knights, on the other.

Most historically aware people know that the Arthur of myth, legend and romance is just that - a twelfth century fiction invented to fit the new chivalric ideology of the medieval aristocracy who has been continuously reimagined by every subsequent era and reshaped in its image. The movies and TV series I enjoyed as a kid are demonstrative, trying to recast the stories of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table for a more egalitarian age. But does the same hold true of the "historical" Arthur? Did he really exist? Or was he himself just as much a fiction/ historical back-projection (albeit of an earlier era) as his mythical counterpart?

"Tis I, Arthur, King of the Britons, Defeater of the Saxons, Sovereign of all England" ... "Pull the other one": The Arthurian legend begins

So, first things first, lets examine the sources for the historical King Arthur and how the legend came to be. Arthur is meant to have lived sometime in the period c.450 - 600. Now I hate to be politically incorrect and break a professional taboo for me as an early medievalist, but unlike on the Continent this period in British history really is a Dark Age. Our only written historical source produced in these Isles during this period is the sermon On the Ruin of Britain by the Romano-British priest Gildas, in which he lambasts the Romano-British rulers of his day and bemoans the onslaught of the invading Anglo-Saxons. Gildas does mention a number of British victories against the Saxons, including the battle of Badon Hill, but he does not mention Arthur anywhere. The key thing to remember, however, about Gildas is that he is writing a hell-fire sermon that's mainly focused on Romano-British moral failure and imminent doom and gloom. It is not a comprehensive historical narrative of this period, and no one can make their mind up as to when exactly Gildas was writing it - a tentative date of c.540 has been raised but he could have been writing two generations earlier or later.

Next we have a poem, attributed to the early seventh century Welsh poet Aneirin, called Y Gododdin, that basically takes the form of a catalogue of elegies. The poem tells of how 363 Welsh warriors ride out from the fortress-palace of Gododdin (Edinburgh) to attack the fortress of Catraeth (Catterick in North Yorkshire), defended by 100,000 Anglo-Saxons, and nearly all of them were slain. From then on, each verse of the poem takes the form of an elegy to an individual warrior, narrating his heroic deeds and death. When gets to the warrior Gwawrddur in verse 99, the poet writes

He fed black ravens on the rampart of a fortress

Though he was no Arthur

Among the powerful ones in battle

In the front rank, Gwawrddur was a palisade.

Now you might be thinking "well this is an almost contemporary throwaway reference to, well you know who. Its clear that he was a real figure from the preceding century and a half, and had become a natural reference point for a martial hero/ formidable fighting machine by the time the poet was writing." Well no, unfortunately its not that simple. You see, like with a lot of the sources for early medieval history, the seventh century original Y Gododdin does not survive to us today. Instead, what does survive is a much later (thirteenth century) copy of Y Gododdin. Thus, like with a lot of other early medieval written sources that have a similar textual history, there are always some scholars who doubt whether the original ever existed, whether in fact Y Gododdin is a high medieval forgery that was then falsely attributed to Aneirin in order to get more people to read it. And while most scholars would argue that a seventh century original did indeed once exist, they would nonetheless argue that the reference to Arthur is likely an interpolation by a later scribe - adding bits in was a very common practice in the transmission of ancient texts. Its for this reason that the nineteenth century German scholars who founded that great collection of medieval texts known Monumenta Germaniae Historia, obsessed over finding the original manuscript (Urtext) of every source. And where they couldn't, they tried speculatively to recreate it by minimalizing the detail as much as possible on the grounds that many of the details in the (later) extant copies were likely interpolations.

|

| Gododdin or, as it now goes by the name of, Edinburgh Castle today |

|

| A modern artist imagines what the 363 Welsh heroes at the battle of Catraeth (c.600), if it ever did happen, would have looked like. Perhaps the military forces commanded by the historical King Arthur would have looked like this too. |

Early in the eighth century, we get some historical writing on the other side, that of the now thoroughly settled Anglo-Saxons. The Venerable Bede, who we know had access to Gildas, in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People (c.731) does not mention anyone called Arthur. One might think that Bede, as an Anglo-Saxon living in a Northumbrian monastery, wouldn't want to record the deeds of a Romano-British/ Welsh hero and so would give him the silent treatment. At the same time, Bede does speak of a heroic Romano-British leader called Aurelius Ambrosius, briefly mentioned by Gildas as the "last of the Romans", who successfully fought back against the Saxons c.450 - c.480 and won some great victories. Bede's reputation as a historian over the centuries has generally been very high, and we'll see later, some later historians have taken Bede's silence on the matter of King Arthur as a clear indication that he didn't exist.

|

| "Hey, I'm looking for King Arthur?" ... "Sorry pal, nothing to see here!" An early ninth century manuscript of Bede's Ecclesiastical History stored in the British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius C II. |

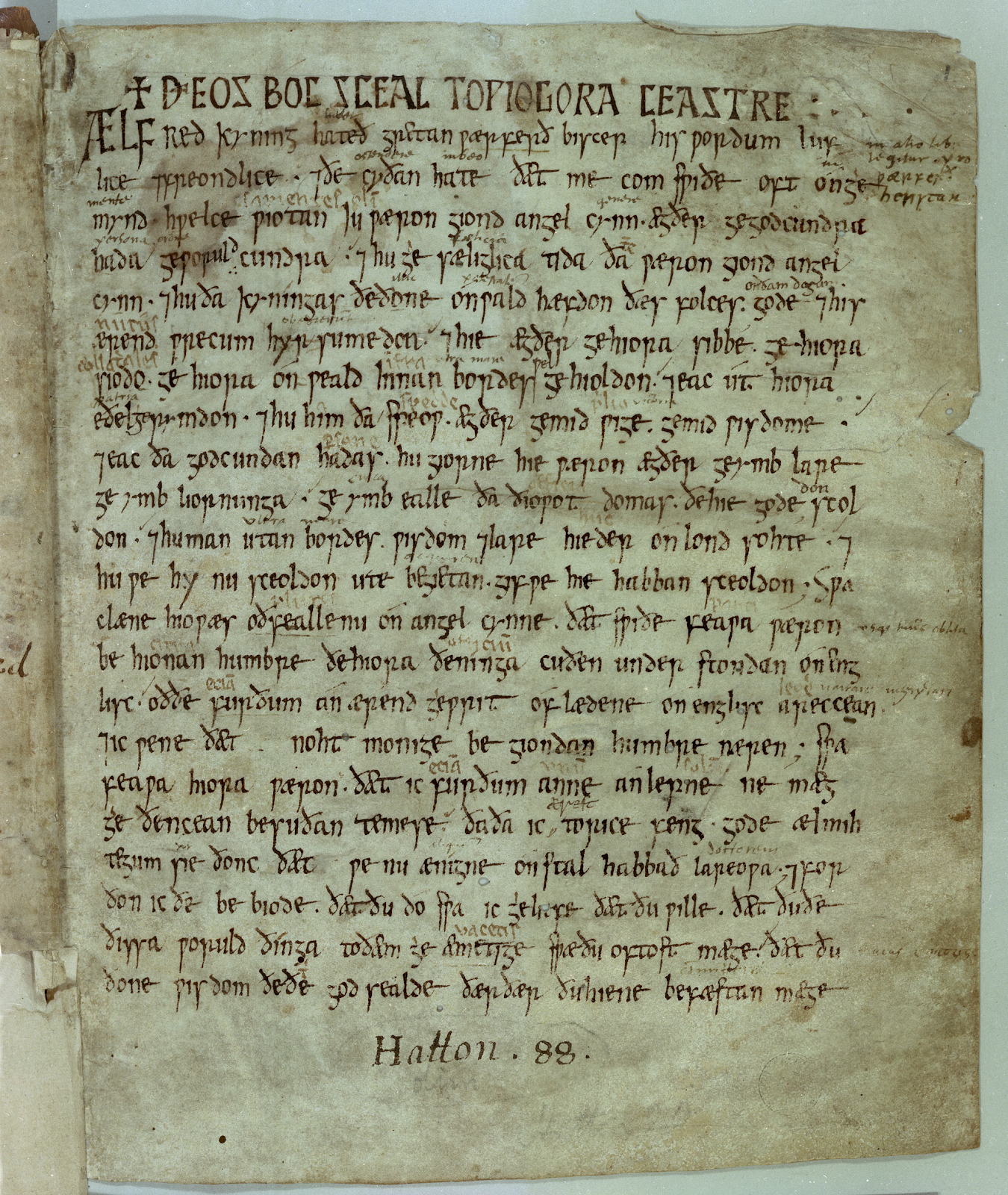

It is in the early ninth century that we at last get our first concrete historical references to King Arthur. Around 829, the History of the Britons was written, an account of Welsh history from earliest times to the present - traditionally, this work was ascribed to the Welsh monk Nennius, but modern scholars reject this view and see the author as an anonymous compiler.

The History of the Britons firstly tells of how the Welsh were, like the Romans, the descendants of the Trojan prince Aeneas, and the author displays a good amount of familiarity with Virgil whilst obviously adding stuff that the Roman poet never mentioned. Then he tells the story of Caesar's invasion of Britain, of the return of the Romans under Emperor Claudius and then a brief narrative of the various Roman emperors who ruled Britain. After the defeat of the usurper Magnus Maximus (d.388), who used the legions stationed in Britain and the support of native chieftains to launch his bid for the imperial throne, the author claims that Britain stopped being part of the Roman Empire and a chap called Vortigern ruled over the Britons as king. The Picts from north of Hadrian's Wall and the Scots from Ireland started to give the Romano-British trouble, so Vortigern welcomed the Saxons, led by the brothers Hengist and Horsa, from over the North Sea to give him a helping hand. Hengist even persuades Vortigern to marry his daughter. But then the Saxons betray the Britons and start conquering the island off them, and Vortigern goes and hides away in North Wales. His son Vortimer successfully leads resistance to the Saxons and kills Horsa, and so the Saxons have to fetch more and more reinforcements from Germany. Hengist then invites all the chiefs of the Britons to a feast under the pretence of making peace, telling his men to conceal their seaxes (short swords), and then they massacre them all except Vortigern, who purchases his freedom by giving the Saxons the regions of Kent, Essex and Middlesex. Vortigern is then condemned by St Germanus of Auxerre, who we know visited Britain in the 430s, and divine retribution is brought down on him - the author is unsure whether Vortigern's palace with everyone inside was burned to ashes by fire and brimstone at night or if the earth opened and swallowed him up. Then after that Aurelius Ambrosius, whom the author refers to as a "king", and Vortigern's sons lead resistance to the Saxons. But once they've passed away, who's gonna lead the resistance against the Saxons? The author says

Then it was, that the magnanimous Arthur, with all the kings and military force of Britain, fought against the Saxons. And though there were many more noble than himself, yet he was twelve times chosen their commander, and was as often conqueror. The first battle in which he was engaged, was at the mouth of the river Gleni. The second, third, fourth, and fifth, were on another river, by the Britons called Duglas, in the region Linuis. The sixth, on the river Bassas. The seventh in the wood Celidon, which the Britons call Cat Coit Celidon. The eighth was near Gurnion castle, where Arthur bore the image of the Holy Virgin, mother of God, upon his shoulders, and through the power of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the holy Mary, put the Saxons to flight, and pursued them the whole day with great slaughter. The ninth was at the City of Legion, which is called Cair Lion. The tenth was on the banks of the river Trat Treuroit. The eleventh was on the mountain Breguoin, which we call Cat Bregion. The twelfth was a most severe contest, when Arthur penetrated to the hill of Badon. In this engagement, nine hundred and forty fell by his hand alone, no one but the Lord affording him assistance. In all these engagements the Britons were successful. For no strength can avail against the will of the Almighty.

And there you have it folks - the first concrete historical reference to King Arthur. All except, he's not actually a king. Rather he's a war leader (dux bellorum) commanding the combined military forces of the various petty kings of the Romano-British. And of course, given that Arthur is turning up in the history books roughly three hundred years after he's supposed to have lived, it does beg the question of how much distorted memory, oral accounts getting more garbled as they pass down the generations and down-right myth-making has taken place in between. Further problems are raised by the fact that the locations of Arthur's battles mentioned in the History don't appear to map on to any present day locations. Also Arthur appears like a massively overpowered superhero - no one has the physical strength to kill 940 men singlehandedly in one day with sword and spear - though it must be said in the author's defence that, so far as we can tell, he sincerely believed that anything was possible with God's intervention. And let's not forget the political context in which the History of the Britons was written. The decades on either side of c.800 were a time of much Anglo-Welsh border conflict. Lets not forget that back in 785, possibly within the author's living memory, King Offa of Mercia (r.757 - 796) had built Offa's Dyke, Britain's largest post-Roman fortification to date, to fend off against Welsh attacks. So in that kind of climate, heroic Welsh war-leaders of exceptional charisma and martial prowess who won battle after battle, pushing back the tide of the Germanic invaders, were very much in demand to provide hope and inspiration in the present day.

|

| Offa's dyke: invaluable context for all these histories of ethnic conflict between Anglo-Saxons and Britons being penned down by both sides in the eighth and ninth centuries. |

Arthur and his battles were recounted again in the Annals of Wales (c.954), which used the History of the Britons as its source material. The Annals give a precise date of Arthur's victory at Badon Hill to 516 AD, and claim that Arthur died in battle against his nephew Mordred (who makes his first appearance here) in 537. Again political context is key - between 927 and 975 various Welsh kings did homage and paid tribute the West Saxon kings of a now-unified English kingdom. Thus histories of Welsh triumphs against the Anglo-Saxons would provide uplifting reading in the tenth century present, when the West Saxon kings held quasi-imperial hegemony over all of Great Britain. Arthur also appears as a character in various Old Welsh poems written in the ninth to eleventh centuries, which strongly suggest that he was already becoming a figure of myth and legend.

King Arthur comes of age

The genius behind the "King" Arthur we know and love is Geoffrey of Monmouth (c.1095 - 1155). As his name suggests, he was from Monmouthshire in Wales, but his ethnicity is unknown and subject to dispute - he might have been a native Welshman, a Norman or even a Breton (William the Conqueror had installed many Breton lords in Cornwall and on the Welsh Marches, including in Monmouth itself). We know he was based in Oxford from 1129 - 1151, where he appears as a signatory to six charters along with Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford. In some of the charters, Geoffrey signs with the title of "teacher" (magister), which strongly suggests that he was an academic at the twelfth century schools in Oxford, which would evolve into Oxford University the following century. It was in 1136 - 1138 that Geoffrey of Monmouth sat down and wrote his History of the Kings of Britain. Geoffrey claimed in the preface that he was simply writing a Latin translation of "an ancient book in the British language [Welsh] that told in orderly fashion the deeds of the kings of Britain." Modern scholars now almost universally accept that the History of the Kings of Britain is a thoroughly original work. Geoffrey drew his historical "facts" from the History of the Britons, Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People and Gildas' On the Ruin of Britain, all of which we've discussed earlier, before filling in the gaps with stories from Welsh bardic poetry and his own invented tales. His History begins with the legendary Brutus of Troy, a great-grandson of Aeneas who settled in Britain, drove out the race of giants that lived there and from whom all kings of Britain and Welsh princes are descended, and ends with the death of the thoroughly historical Welsh king Cadwaladr in 682 AD, whose exploits are recorded by Bede. Geoffrey of Monmouth's History is also the oldest source to mention King Lear and Cymbeline, both of whom Shakespeare would later write plays about for James I.

|

| King Lear and his three daughters depicted in the margins of Matthew Paris' Chronicle (c.1250) |

But first and foremost, Geoffrey of Monmouth is famous for the King Arthur stuff. Geoffrey elaborates more on Arthur's backstory. In his History, Arthur is the grandson of the the late Roman usurper Constantius III (d.421), and the son of Uther Pendragon, the youngest of Constantius' three sons, the elder two being Constans and Aurelius Ambrosius, making them Arthur's uncles. The evil Vortigern kills Constans, and becomes the tyrannical ruler of Britain. It is here that the figure of Merlin is introduced for the first time - when Vortigern is building his fortress of Dinas Emrys in Snowdonia he meets Merlin, who shows him two dragons, a red one symbolising the Welsh and a white one symbolising the Saxons, fighting in a cave underneath the castle, and prophesises all the historical events in Britain that will follow, as well as the ultimate triumph of the Welsh over the Saxons (as of yet, still unfulfilled but, with Boris Johnson being so all-around crap, almost like a latter day Vortigern, maybe Plaid Cymru will get their chance!)

|

| Merlin shows Vortigern the two dragons at Dinas Emrys, as depicted in a mid-fifteenth century manuscript |

After Vortigern meets his much deserved end, Aurelius and Uther take over ruling the Britons. Aurelius dies and Uther takes over. Uther holds a feast for all his vassals, and during the feast gets the hots for Igraine, the wife of Duke Gorlois of Cornwall. Igraine realises that Uther is interested in her in that way, and so hides away in her husband's castle of Tintagel. Uther declares war on Gorlois and lays siege to his castles. While Gorlois is out fighting Uther's armies, Merlin gives Uther a magic potion that will enable him to temporarily assume Gorlois' form. Uther sneaks into Tintagel, Igraine is under the illusion that its her husband, they passionately make love and Igraine gets impregnated with Uther's baby - none other than our hero, King Arthur! I'm not sure how medieval people felt reading about the circumstances of Arthur's conception, but to modern audiences Uther's behaviour would come across as creepy.

|

| Tintagel, Cornwall, site of Arthur's conception according to Geoffrey of Monmouth. Luxury goods dating to the sixth century from the Eastern Roman Empire have been found at Tintagel, a strong indication that it was a seat of power for a Romano-British tribal leader or king in the fifth and sixth centuries - its certainly quite an imposing site, perfect for building a palace or stronghold. Maybe the folk memory of this survived in Geoffrey of Monmouth's time. Richard, earl of Cornwall (1209 - 1272), the younger brother of King Henry III was so into Geoffrey of Monmouth's Arthurian tales that he had his own castle built at Tintagel of which only part of the rampart still survives, as you can see in the image. |

Duke Gorlois dies in battle that night, and when Igraine hears the news she wonders "who the fuck slept with me last night then!" For her own security, she marries Uther, and together they raise the boy child, the true identity of his father being kept secret. When Uther dies, Arthur succeeds him and defeats and subjugates the invading Saxons in a sequence of epic battles (the same as given in the History of the Britons but with the detail more fleshed out). With England and Wales under his command, Arthur then proceeds to conquer Ireland, Scotland, the Orkney and Shetland Islands, Iceland (of all places), Norway, Denmark, Germany and France. Twelve years of peace and prosperity ensue. Then, after the Britons refuse to pay tribute to the Romans like they did in the past, the Roman Emperor Lucius declares war on them, but Arthur defeats Lucius in battle, kills him and conquers Rome. But just before Arthur can sit down to rule his empire, spanning the whole of Western Europe, his nephew Mordred betrays him, by marrying Queen Guinevere and usurping the throne. They fight a battle at Camlann, Mordred is slain but Arthur is mortally wounded and in his dying moments he is carried off the Isle of Avalon to be put into an enchanted sleep. He gives his kingdom to his cousin, Duke Constantine of Cornwall. War with the Saxons resumes, and in the end they conquer all of Lloegyr (England) and the Britons are confined to Wales and Cornwall.

Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain was an immediate bestseller. It gave England and Wales an ancient history of comparable richness and depth to that of Greece, Rome or France, and a great leader to rival Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar or Charlemagne. Combine that with Geoffrey of Monmouth's contemporaries, William of Malmesbury (c.1090 - 1143), Henry of Huntingdon (c.1100 - 1157) and Geoffrey Gaimar (fl. 1130s), writing about the glories of the Anglo-Saxon past, and what you had was a cocktail to make the still fairly recently established Norman aristocracy absolutely euphoric.

Not only did Geoffrey help the Normans identify more strongly with the lands and peoples they had conquered since 1066, he also provided some solid epic foundations for poets to build on. These poets, who depended on the patronage of royal and noble courts for their living, proceeded to adapt Geoffrey's work to meet the demands of the secular, courtly noble and knightly audiences that would be consuming them.

In 1155, the Norman poet Wace wrote an Anglo-Norman French rendition of Geoffrey of Monmouth's History called the Deeds of the Britons. Wace did his best to adapt Geoffrey to his audience. He removed the prophecies of Merlin in Book 7 as they were too politically charged for King Henry II and the Norman aristocracy. To fit in with the refined sensibilities of his courtly audiences, he cut out the descriptions of exaggerated sentiment and excessively brutal and barbaric behaviour from Geoffrey's History. He provided more dialogue and more detailed descriptions of battles, the splendour of King Arthur's court, the beauty of its ladies and the gallantry of its knights. But, most importantly of all, Wace wanted to meet the twelfth century aristocracy's demand for fiction, that is to say for literature that treated its characters as unique individuals and explores their thoughts, emotions, motivations and interior worlds. All of this was very much in step with the general direction of twelfth century culture more generally - in particular the growing celebration of the individual, the leisured life and romantic love. Emblematic of this, as Laura Ashe has observed, is a dialogue Wace writes between two of Arthur's knights, Cador and Gawain (later to be of Green Knight fame), after its been announced that Arthur is going to war with the Emperor Lucius. In Geoffrey of Monmouth's original, Cador says that going to war is good because the twelve years of peace and prosperity have made the Britons grow soft and cowardly, and so they must regain their reputation for martial valour. Wace includes this, but deviates from his source material by adding a response from Gawain. Gawain tells Cador that peace is good, for the land and people prosper from it, and then adds "Pleasant pastimes are good, and so are love affairs. It's for love, and lovers, that knights do knightly deeds."

This example also reflects one of the main purposes of the emerging genre of chivalric and courtly literature that Wace's work was pioneering in - to encourage debate amongst its readers. Twelfth Norman century knights, who would have listened to this being read aloud at mealtimes in the royal and noble households they served in, would have had to ask themselves these question "Is Cador or Gawain right?" "For who and for what should we perform great deeds of prowess and courage?" "Is it better to live the austere, disciplined life of the the straightforward warrior, or the leisured, sensual life of the knight as courtier, poet and lover." This was, in effect, one of the central debates on chivalry for the next 350 years or so.

|

| A knight from the Hunterian Psalter, c.1170. Wace and subsequent Arthurian writers wrote with people like this guy, and their desires, aspirations and struggles, in mind. |

I emphasise debate because that's fundamentally what chivalry was. Chivalry was NOT something static and written in stone. It was a living, contested and evolving ethos. Too often modern scholars make the error of slipping into talking about a "Code of Chivalry" as if knights had a special pocket in the mail hauberks for a parchment scroll containing "Ye Olde Code of Chivalry" (or whatever local vernacular equivalent), which conveniently told you what the chivalrous thing to do was in any given situation. What was universally agreed upon was that there was a certain set of (roughly) six values that all knights should uphold - prowess, courage, loyalty, generosity, piety and courtesy. Beyond that, everything, including which order of precedence these values came in (though, almost consistently, prowess came at the top), was open to debate. Every work of chivalric literature, especially the Arthurian romances, was in its own way a contribution to that debate, as well as being designed enable its consumers to see themselves, their aspirations and their struggles in the fictional knights performing superhuman feats in a magical landscape. This is why Arthurian romances absolutely SHOULD be taken seriously as historical sources. Like with any historical source, so long as you know how to read them carefully, contextually and critically, they are as valid as any other kind of source.

Enough digressions! One of Wace's most lasting contributions to Arthurian romance was the Round Table. Wace explained the table's circular shape on the grounds that Arthur's barons and knights would not argue over precedence, as would inevitably be the case with seating arrangements on any polygonal table. Aristocratic societies, especially ones so focused around royal and princely courts, are inevitably very conscious of rank, status and lineage and whether they are being correctly observed and given due respect. But in many ways, Wace and other early chivalric writers are trying to argue against that tendency - that rather than there being a complex pecking order, there should be a sense of oneness and common purpose at court. And in much subsequent chivalric literature, we find the idea that the measure of a man's worth should not be his rank, status or lineage but his character and deeds. Indeed, in 1173, 18 years after Wace wrote his Deeds of the Bretons, Henry the Young King, son of King Henry II, chose not to be knighted by his father-in-law, Louis VII of France, but by a household knight from the lowest rung of the landed aristocracy called William Marshall, "the greatest knight there ever was, or ever will be." This is a process that modern historians call the "birth of nobility." In 1100, the nobles (dukes, counts and barons) saw themselves as a class apart from the knights, whose landholdings (if they had them at all) were relatively small and most of whom were the third, second or even first generation descendants of peasants. By c.1225, however, all knights had been accepted into the nobility, all male nobles of whatever rank identified as knights, with the dubbing ceremony now being a universal right of passage, and they all intermarried and followed the same code of conduct. The work of early chivalric writers like Wace were both witness to and actively shaped this social transformation.

|

| The first ever known artistic depiction of Stonehenge, in an early fourteenth century manuscript of Wace's Deeds of the Britons |

Thus with Wace, the Arthurian legend lost all of its original moorings in the world of sub-Roman and early medieval Britain, which were still to some degree there in Geoffrey of Monmouth. Instead, it became anchored in the world of the twelfth century present - to meet the demands for new kinds of literature and as a vehicle for exploring new sensibilities, values and ideas to shape the new ethos of chivalry.

After Wace, the poet Chretien de Troyes (c.1130 - 1190) wrote Old French Arthurian romances for the courts of the Dukes of Brittany and the counts of Champagne and Flanders. It is he who really delves into the stories of Arthur's individual knights, making Arthur into a bit of a supporting character. Lancelot and Percival are introduced into the Arthurian universe by Chretien, each of them being the central protagonist of one of his romances, and thus Lancelot's adulterous courtly love affair with Guinevere and the quest for the Holy Grail are brought into the mix too.

|

| Perhaps Chretien de Troyes' most important (and incendiary) contribution to the Arthurian canon). Lancelot kisses Guinevere with Galahad and the Lady of Malohaut as his witnesses in the Book of Lancelot (c.1316). Whether Lancelot or Galahad was a better role model for knights was never entirely clear. On the one hand, Galahad's celibacy was a difficult act to follow for most knights - indeed, it was meant to be. On the other hand, woe betide any knight who tried to seriously emulate Lancelot in an having affairs with a high-born married lady! In 1175, Count Philip of Flanders caught his wife Elizabeth of Vermandois having an affair with a courtier, Walter de Fontaines, and had her lover beaten bloody and left to die hanging upside down over a cesspit. The best course of action for most was to stick to casual flirting games with the ladies of court, but never escalate things any further, and wait till a sensible woman, or if you were lucky a rich heiress or widow, came your way. |

After Chretien de Troyes, the Arthurian universe just keeps expanding, with various characters, places and events touched upon only cursorily in previous romances getting their own storylines. One can see the Arthurian romances kind of like the MCU Avengers or the DC Justice League, constantly generating spin-offs, fan-fictions and next generation retellings. Something like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (c.1400) written in Middle English by the anonymous Gawain poet, can be seen in this light potentially. Every addition to the great expanse of Arthurian literature reflected the particular flavour of the moment and the interests and concerns of its author. By the time of the Wars of the Roses, it would befall a certain Thomas Malory to tie all the disparate threads together in his Le Morte d'Arthur (1485). The author, a practicing knight himself, drew from all the Arthurian literature available to him in Latin, Old French and Middle English to create a comprehensive epic that would meet the demands of a readership that now had a very large middle class component. It is Malory's Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table that have inspired poets, artists, novelists, composers, film-makers and video games designers ever since, and thus it is they that form the basis of the Arthurian legend as we know it.

|

| An Arthurian Avengers assemble? The frontispiece of the 1634 edition of Thomas Malory's Morte D'Arthur. I can imagine John Milton would have read this as he does allude to the Arthurian romances in Paradise Lost, and Charles I and all the red-blooded Cavaliers definitely would have. Godly Puritans would have likely found much of it totally objectionable (Lancelot and Guinevere, for starters!), and Thomas Hobbes would have likely turned his nose up at it too. But this is just me engaging in idle speculation. |

Medieval debates on King Arthur's existence

This is in fact a debate that's been going on since the twelfth century. Indeed, as soon as King Arthur mania had consumed England and France and was poised to engulf the whole of Latin Christendom, William of Newburgh (1135 - 1198) attempted to deliver a blow with a sledgehammer to this new historical hero and cultural icon. In Chapter One of Book One of his History of English Affairs he wrote:

"A writer in our times has started up and invented the most ridiculous fictions concerning them (the Britons) … having given, in a Latin version, the fabulous exploits of Arthur (drawn from the traditional fictions of the Britons, with additions of his own), and endeavoured to dignify them with the name of authentic history; moreover, he has unscrupulously promulgated the mendacious predictions of one Merlin, as if they were genuine prophecies, corroborated by indubitable truth, to which also he has himself considerably added during the process of translating them into Latin… no one but a person ignorant of ancient history, when he meets with that book which he calls the History of the Britons, can for a moment doubt how impertinently and impudently he falsifies in every respect… Since, therefore, the ancient historians make not the slightest mention of these matters, it is plain that whatever this man published of Arthur and of Merlin are mendacious fictions, invented to gratify the curiosity of the undiscerning… Therefore, let Bede, of whose wisdom and integrity none can doubt, possess our unbounded confidence, and let this fabler, with his fictions, be instantly rejected by all.”

William of Newburgh would not have the popularity and influence of Geoffrey of Monmouth, Wace or Chretien de Troyes. To top it all up, in 1189, the monks of Glastonbury had 'proved' King Arthur and Queen Guinevere to have really existed by unearthing their graves, making their abbey something of a tourist attraction. So one might presume that William of Newburgh's sound, source-based historical criticisms were simply falling on deaf ears.

|

"The most ridiculous fictions": A copy of the "History of the Kings of Britain" produced c.1160 at Mont Saint-Michel in Normandy, now contained in the Bibliotheque Nationale de France in Paris. The fact that we have 220 surviving medieval manuscript copies of this work is no mere accident, being instead demonstrative of its widespread popularity. See below for another manuscript folio from a twelfth century copy of Geoffrey's "History."

|

Yet its nonetheless interesting to note that in the late fifteenth century, around the time Sir Thomas Malory was penning down the most complete and authoritative version of the Arthurian legends, Le Morte d'Arthur, a substantial number of educated lay men were expressing opinions remarkably similar to those we saw earlier from William of Newburgh on King Arthur's supposed historical existence. In his preface to the first printed edition of Le Morte d'Arthur in 1485, the great businessman, diplomat and translator William Caxton (1422 - 1491) stated that "many noble and dyvers gentylmen" pushed for him to publish a book about King Arthur, one of the "Nine worthy" men. The Nine Worthies were a pantheon of heroes serving as moral exemplars to all lay men, which also included Joshua, David, Judas Maccabeus, Hector, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Charlemagne and Godfrey of Bouillon. Caxton then recounted that when he had presented a book on the deeds of Godfrey of Bouillon, the hero of the First Crusade and first "King" of Jerusalem, to King Edward IV, the Yorkist king requested that his next book be about Arthur because he was "English" and there were so many sources about him.

Yet, and here is where it actually gets interesting, Caxton responded to the king by saying "that dyvers men holde oppynyon that there was no suche Arthur, and that alle suche books as been maad of hym ben but fayned and fables ... bycause that somme cronycles make of hym no mencyon ne remember hym noothynge, ne of his knyghtes.”

Unless Caxton really was just playing devil's advocate for the sake of it, this would seem to imply that in the late fifteenth century, a substantial lay reading public in England were becoming so well aware of their country's chronicle record that they were capable of fairly sophisticated historical criticism of Arthur's existence. Caxton himself however, did not doubt Arthur's historical existence and pointed to learned authorities, including Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain, Ranulf Higden's (1280 - 1360) Polychronicon, Giovanni Boccaccio's (1313 - 1375) On distinguished men, as well as physical evidence - the graves at Glastonbury, the Round Table at Winchester, the ancient seal at Westminster in "reed [red] waxe closed in beryll” bearing a Latin inscription that translates as "Arthur the Patrician, Emperor of Britain, Gaul, Germany and Denmark [Dacia]," Gawain's skull at Dover castle and Lancelot's sword at an unspecified location. Caxton concluded “al these thynges considered, there can no man reasonably gaynsaye but there was a kyng of thys lande named Arthur,” but he did also say “for to passe the tyme, thys book shal be plesaunte to rede in; but for to gyve fayth and byleve that al is trewe that is conteyned herin, ye be at your lyberté.”

|

| In the Middle Ages, King Arthur was far from being a parochial figure or even an Anglo-French one. While debates were raging in England about his historicity, the elites rest of Latin Europe were absolutely obsessed with Arthur and his knights. Above is an early fifteenth century image of King Arthur from the Nine Worthies fresco cycle at the Castello della Manta in Piedmont, Italy, commissioned by Tommaso III, Margrave of Saluzzo (1356 - 1416). Tommaso was a cultured and learned man who took chivalry very seriously, to the point that, like a number of other knights in the late middle ages, he even wrote a treatise on it in Middle French, Le Chevalier Errant (all Italian aristocrats of his day would have been fluent in French as well as their native dialect - it was invaluable for business and diplomacy, and was on track to replacing Latin as the leading literary language of Europe). |

|

Not only did King Arthur and the Round Table make their way over the Alps, they even managed to corner the literary market in Eastern Europe as well. This fresco was commissioned sometime in the 1330s to decorate the great hall of the tower-house of Duke Henryk I of Jawor (1292 - 1346) at his manor of Siedlecin in Poland. This fresco tells the story of Sir Lancelot, one of only two surviving frescoes of its kind and the only one in its original location and context - the other Lancelot fresco is at a museum in Alessandria, near Turin in Italy. The fresco is meant to be read clockwise. The first scene depicts Camelot and Queen Guinevere and her entourage setting out. Then Lancelot defeats the villainous Malageant in single combat after he tries to abduct Guinever and her entourage. Finally, while Sir Lionel sleeps under a tree, Lancelot, who has been beguiled by Guinevere's exceptional beauty, begins his adulterous affair with her.

|

|

| Our stereotypes of Medieval Jews would tells us that they were aloof from this pan-European Arthurian mania. They were all sober traders, moneylenders, doctors, philosophers and rabbis weren't they? Wrong! Jews were more integrated into the mainstream of medieval culture than we've often been taught to think, and they loved stories of magical adventures, epic conflicts, daring and courteous knights, beautiful women in need of rescuing and steamy romantic affairs as much as anyone did in the Middle Ages. Indeed they even wrote their own versions of the stories of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, like the Melekh Artus, written in 1279 as an abridged Hebrew version of the early thirteenth century Old French Vulgate Cycle (a complete rendition of the Arthurian legends), and sometime in the fifteenth century a Yiddish speaking Jew sat down and wrote Viduvilt, an adaptation of the Middle High German Arthurian romance Wigalois (c.1220) by the knight Wirnt von Grafenberg. Jews also wrote chivalric romances with their own imagined, Jewish knights and ladies like Maskil and Peninah (thirteenth century) and the Bovo Bukh (1541). The image above is from a Jewish prayer book c.1320, now in the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, which shows that chivalric imagery was even interwoven into Jewish religious devotional activities. |

The Renaissance in the service of Arthuriana: John Leland and the King Arthur debate in Tudor England

In the sixteenth century King Arthur's existence still had plenty of learned defenders. John Leland, one of the greatest historians of the English Renaissance and an early pioneer in the archaeology of Roman Britain, would write in 1542 that not only did King Arthur definitely exist but that he had pinpointed the location of his capital, Camelot, to the ancient British hillfort of Cadbury, located between the villages of Queen Camel and West Camel in Somerset:

"At the very south ende of the chirch of South-Cadbyri standeth Camallate, sumtyme a famose toun or castelle, apon a very torre or hille, wunderfully enstregnthenid of nature.... The people can telle nothing ther but that they have hard say that Arture much resortid to Camalat" (Leland's Itinerary).

|

| "Camelot! Camelot! Camelot!" The hillfort of South Cadbury in Somerset, more about that later ... |

In identifying South Cadbury as Camelot, Leland had actually broken with his twelfth century predecessors, Geoffrey of Monmouth and Chretien de Troyes, who had identified the location of King Arthur's court as "the City of the Legions", Caerleon in Gwent, southeast Wales. William Caxton had also pinpointed the location of Camelot as being in Wales, and was probably referring to Caerleon when he wrote in his preface to Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur that many people had seen in "Camelot" great stones, marvellous works of iron and royal vaults lying underground. In this respect Caxton disagreed with Malory himself, who believed that Camelot was at Winchester in Hampshire on the basis of the surviving Round Table there, though he did believe Arthur had been crowned at Caerleon. What Caxton says raises interesting questions. Did more of the Roman site at Caerleon survive in the fifteenth century than does today? And were archaeological excavations already going in late medieval England?

|

| The Roman amphitheatre at Caerleon in Wales. Unlike a lot of Roman amphitheatres, like the one at Chester, its remains survived above ground, and thus Geoffrey of Monmouth himself saw it, as presumably did the fifteenth century English men and women mentioned by Caxton. |

Leland would write two stand-alone treatises in the 1540s defending the historicity of King Arthur and Geoffrey of Monmouth's credibility as a historian against all doubters. As a patriotic Englishman he saw them as integral to the glorious history of his native land. In these endeavours, he made use of a range of literary, toponymical (place name) and archaeological evidence, as well as local oral traditions and folklore he'd picked up on his travels through England and Wales, which may otherwise have never been preserved. I must say that I find John Leland a really admirable figure. However much we might ridicule him as credulous and parochial for believing in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Pseudohistory and local folklore, he was a highly intelligent scholar and a real pioneer in Roman archaeology. At Lincoln, for example, he noted three stages of the development of the settlement - the first being the British settlement at the top of the hill where "much Romaine mony is found", the second being the Saxon and medieval settlement to the south and the third being the recent suburb of Wigford on the riverside. He correctly identified that the existing masonry above ground at Ripon cathedral, founded in 672, "indubitately was made sins the Conquest." He also successfully identified the brickwork at Verulamium in Hertfordshire, Richborough, Dover and Canterbury in Kent and Bewcastle in Cumbria was Romano-British. Most extraordinarily, at the hillfort at Burrough Hill in Leicestershire, he produced what was in effect the first archaeological field report - he pulled some stones he found at the gateway to establish whether the earthen ramparts had had a wall on them, saw that they were mortared with lime and deduced that it had been. Figures like him really make us think about the boundaries we draw between medieval and renaissance. One the one hand, Leland was a humanist scholar trained at the University of Paris whose methods as a historian and antiquarian were cutting edge for the sixteenth century. Yet on the other he still believed resolutely believed in the twelfth century Arthurian legends and romances of Geoffrey of Monmouth and Chretien de Troyes, unlike the much more sceptical and source-critical William of Newburgh more than 300 years before him.

|

| An engraving of an eighteenth century bust of John Leland at All Souls' College, Oxford |

|

| The Round Table at Winchester, originally made (c.1300) for an Arthurian re-enactment tournament by Edward I, which Henry VIII then had re-painted in 1520 with a Tudor Rose in the middle, to impress his nephew Emperor Charles V. There's no doubt that Henry VIII believed that King Arthur was a real person, and took belief in him very seriously. Henry's father, Henry VII, had claimed descent from King Arthur via his Welsh princely ancestors to help bump up his shaky legitimacy, and Arthur's Empire spanning half of Europe, including Rome itself, described by Geoffrey of Monmouth served as a model, along with the Christian Roman Empire of Constantine and Justinian, for Henry VIII when he declared England to be an Empire in 1534 to signify his independence from the pope's authority. |

The King Arthur debate in the modern era

Now what have scholars thought of King Arthur's historicity in the modern era? When history as a formal academic discipline taught in universities emerged in the Victorian Era, the great English medieval historians of the nineteenth century - Edward Augustus Freeman, Bishop William Stubbs, Frederick William Maitland and John Richard Green - were not at all interested in questions of what was going in the fifth and sixth centuries from the Romano-British side. The chivalric King Arthur that Chretien de Troyes and Thomas Malory had written about, stoked the fires of the imaginations of the poet Alfred Tennyson (1809 - 1892) and the pre-Raphaelite painters, Edward Burne-Jones (1833 - 1898), William Morris (1834 - 1896), John William Waterhouse (1849 - 1917) and Edmund Blair Leighton (1852 - 1922) - who associated the medieval past with truth, beauty and innocence, in contrast to modern industrial society, and Arthur and his knights as models for what the modern man should be. In great contrast, the historians of nineteenth century England didn't give two flying monkeys about this legendary figure, or what historical reality might have been behind him.

|

| King Arthur and Sir Lancelot (1862), a mock fourteenth century stained glass window by William Morris. The Latin inscriptions read (my translation) "Arthur The Great, England's Most Powerful King" and "The Lord Lancelot, Unconquered Knight" |

|

| "Last Sleep in Avalon" (1881) by Edward Burne-Jones |

|

| Perhaps the most famous pre-Raphaelite painting of all, "The Lady of Shallot" (1888) by John William Waterhouse, inspired by Tennyson's 1833 poem which was in turn inspired by a thirteenth century Italian ballad |

|

| "The Attainment of the Grail" (1895) by Edward Burne-Jones, in a cycle of tapestries about Sir Galahad designed for the British businessman William Knox d'Arcy, one of the principal founders of the oil and petrochemical industry in Iran (then called Persia) for his dining room at Stanmore Hall. |

|

| "Tristan and Isolde: The End of the Song" (1902) by Edmund Blair Leighton, based on an Old French Arthurian romance written no later than 1240. It really is a wonderful painting with a lot of high drama. Tristan has just finished serenading Isolde and is about to lean in for a kiss, Isolde is like "I don't know, Tristan. What if someone sees us?", and King Mark of Cornwall (Isolde's husband), completely oblivious to what is really going on, is about to walk in on it all. |

Instead, what they wanted to tell was a different story, yet one that would ultimately turn out to be at least as mythological. The story went thus. In the fifth and sixth centuries an unstoppable onslaught of Anglo-Saxon immigrants from across the North Sea drove the Romano-Britons into the hills and valleys of the far west (Wales, Cornwall and Cumbria) and put the rest to the sword. These Anglo-Saxons were of superior Teutonic racial stock, and they brought with them their self-governing proto-democratic institutions from the forests of Germany, as described by the Roman historian Tacitus. Thus, as Victorian English historians told it, the English were born as liberty-loving Germanic nation, and thus it was almost written in their DNA that they would dominate the insular Celts, create the "mother of all parliaments" and through the British Empire spread liberty, prosperity, the rule of law and democratically-elected assemblies around the globe. It was for this reason that the preoccupation of Victorian British medievalists was with constitutional history - the evolution of English law and governmental institutions from those primeval Germanic origins all the way through the Anglo-Saxons, Normans and Angevins to the "Lancastrian Constitutional Experiment" with parliamentary government, the aristocratic anarchy (as they saw it) of the Wars of the Roses and the despotic monarchy of the Tudors. In great contrast to Leland's day, English nationalism had completely outgrown King Arthur - it was now abundantly clear that the Arthur of later medieval romance couldn't have existed, England's history was glorious enough without him and he was a Celt, not a Teuton; biological race was now integral to the construction of nationhood. So far as the worship of great men (as opposed to that of institutions like parliament, the shire-moot and the common law) was needed, the solidly historical Alfred the Great - unifier of the Anglo-Saxons, defeater of the Viking invaders, great law-giver and respecter of the rights of freeborn Englishmen, founder of the Royal Navy, intellectual monarch and paragon of muscular Christianity - had filled up the Arthur-shaped hole. Victorian English historians were thus content to write off Arthur as a mythological figure and leave him to the fertile imaginations of the poets and artists.

|

| Victorian triumphalist Anglo-Saxonism: The statue of Alfred the Great at Winchester erected in 1899 to mark the thousandth anniversary of his death. |

As you would expect, this essentially racist narrative of what happened in post-Roman Britain was met in Wales, Scotland and Ireland with much offence. It was thus up to Welsh, Scottish and Irish scholars to give a more sympathetic view of the Romano-British, argue for them having put up a bit more of a fight against the Continental invaders and explore the question of whether or not King Arthur was a real person.

There were various views on this issue. The Scottish historian William Skene argued in 1868 that there was a real, historical King Arthur behind the later, wildly implausible legends and that he really had put up a strong, effective resistance to the invading Saxons, though interestingly he suggested the Arthur was not based in Wales or the South West but in the North. The Welsh scholar Sir John Rhys argued in 1891 that there were two Arthurs. One was a mythical figure, with his ultimate origins as an ancient British god, a kind of "Celtic Zeus." The other was a historical figure, a fifth century Comes Brittaniarum in charge of the small remnants of the late Roman field armies who defended the island from the Saxons. The great Welsh historian J.E Lloyd also argued for a historical King Arthur, but placed him southern England, fighting the incoming Saxons there. As he saw it there were two Romano-British military commands (based on the Roman provincial structure), one led by firstly Vortigern and then Arthur guarding against the Saxons in the south and east of Britannia, and one in the north and west fighting against the Picts and Irish. The latter front saw more success for the British, who secured lasting supremacy in Wales and Cumbria. He also argued that there was no British migration westwards which would leave as the only option for proponents of a racially pure English nation the improbable level of slaughter and genocide proposed by John Richard Green.

In the interwar period, R.G Collingwood and J. Myres' Roman Britain and the Germanic Settlements (1935) in the pioneering new Oxford History of England helped stimulate some interest in the Romano-British as more than just passive victims and in the possibility of a historical King Arthur among the English academic establishment. Using texts and archaeology, Collingwood and Myres argued for an effective Romano-British resistance to the Saxons and for Arthur as a formidable Romano-British dux bellorum (warleader) who won many victories and held back the Saxons for some decades. The big game changer was, however, going to be WW2. WW2 made the Germanist thesis beloved of Victorian historians politically and morally repugnant with its celebration of Teutonic racial purity and Romano-British genocide, which sounded too eerily like what the Nazis were on about. And not long after that came the cultural revolutions of the 1960s, which advocated a clean break with the beliefs and attitudes of past generations and the casting away of all that Victorian cultural baggage mid-twentieth century Britons were still burdened with. In fashion, sex and religion alike, the generation that came of age in the 1960s was more different from their parents' generation than any generation before them. England was now a multi-cultural, multi-ethnic nation, and so it felt more than right to celebrate the Celtic contribution to Englishness, which also fitted in nicely with the other elements of cultural and spiritual change at the time. This they could do by focusing on the Romano-British side of things in the fifth and sixth centuries and their legacy going forward - to which they could enlist the maturing science of genetics, which would help lay to rest the genocide theory once and for all. In popular culture Arthur felt like the perfect hero for Post-war Britons to look up to - a charismatic macho warrior hero but without the taint of Teutonism (which Alfred the Great could not protest in his favour), indeed one who had been victorious against invading Germans (Winston Churchill as a latter day King Arthur?) Indeed, what is very noteworthy, is that the British Union of Fascists never appropriated the figure of King Arthur, to which we may thank the legacy of Tennyson and the pre-Raphaelites - Arthur was clearly too tweedy, cuddly and sentimental and not enough of a stern-faced, Darwinian Ubermensch for Oswald Moseley and his gang of thugs. Indeed, in 1958, T.H White in his "The Once and Future King", sequel to his "Sword in the Stone" (the book that inspired the 1963 film) and retelling of Thomas Malory, had portrayed King Arthur as a democrat, pacifist and anti-fascist hero, the renegade knight Sir Agravaine as a Mosleyite figure and Merlin prophesising "an Austrian ... who plunged the civilised world into misery and chaos."

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, Camelot became a metaphor for the White House under the progressive presidency of JFK, who dinted the White Anglo-Saxon Protestant ascendancy by taking pride in his Irish Catholic heritage and was seen as a sort of latter day King Arthur. Celebrating Germanic heritage was out and celebrating Celtic heritage was in on both sides of the Atlantic, so Arthur appeared like the right kind of cultural icon to have for the post-1945 Anglosphere, while Alfred the Great (still receiving much attention from academic Anglo-Saxonists) became increasingly marginalised in popular culture. The Rosemary Sutcliffe novel I mentioned at the beginning of the post emerged very directly out of this post-war valorisation of King Arthur, and much of the Arthurian media I enjoyed as a kid ultimately stemmed from it.

Perhaps not coincidentally, in 1965, twenty years after the defeat of Nazi Germany, in the year of Winston Churchill's state funeral and just as the cultural revolution was entering full swing on both sides of the Atlantic, a great victory for proponents of a historical King Arthur was scored. A team of archaeologists led by Ralegh Radford, who had previously excavated the fifth and sixth century Romano-British royal stronghold at Tintagel (the place where, in Geoffrey of Monmouth, Uther Pendragon made love to Igraine and conceived Arthur) and the Iron Age ringfort at Castle Dore (both in Cornwall), and Leslie Alcock formed the Camelot Research Committee and began excavating at South Cadbury Hillfort (told you it would come up again!) From 1966 to 1970 they excavated the site and found that the site, which had once been a pre-Roman Iron Age hillfort, was resettled in the fifth century AD before being abandoned again by the early seventh century. Among the things they excavated there were a massive post-Roman rampart, the outline of a cruciform church and an isled hall in which luxury ceramics from the Mediterranean were found. All of these finds were clear signs that the site was inhabited by a Romano-British ruler of considerable wealth and power, and it was too irresistible to conclude that this ruler was none other than King Arthur! It thus seemed clear that John Leland hadn't been simply misled by silly West Country folktales after all - in fact, he'd been remarkably prescient in identifying South Cadbury as Camelot.

|

| A putative reconstruction of what the hillfort of South Cadbury would have looked like c.500 AD according to Alcock et al's 1966 - 1970 excavations. Art by Peter Dennis - source: British Forts in the Age of Arthur, Osprey (2008). If not Camelot, then certainly the seat of power of a Romano-British tribal leader of more than average means. |

The support for King Arthur from academic archaeologists gave a green light for historians. In 1973, John Morris, an ancient historian based at University College London, wrote the Age of Arthur: A History of the British Isles from 350 to 650. It was a bestseller and has never been out of print ever since, going through a number of editions. Its important to note that Morris was a serious academic scholar, not a romantic or a crank. Earlier in his career he had worked on the first two volumes (covering the period 260 - 527) of the Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, in collaboration with two other eminent late Romanists, A.H.M Jones and John Martindale. Prosopography, one of those ghastly, long-winded words us historians have to use, essentially means writing a collective biography of all known individuals per se or of a certain profession or social group in a given period - it was first pioneered by German historians in the 1890s studying Roman aristocrats from the early imperial period. Basically, you ascertain all the facts you can know about a historical figure's life from the documentary record (the who, where, when and what) and then try to trace connections and patterns between them and their contemporaries of a similar occupation or social standing. Its a really sober, meat and potatoes, straight up and down, cheddar cheese, chicken tikka masala kind of historical enquiry that's very good for giving us the nuts and bolts needed for further research into the political and social history of a period. Outside of academic life, Morris was an outspoken socialist and anti-war campaigner.

Morris made extensive use of all the textual sources and archaeology, to produce a monumental 665 page book, and he aimed at a comprehensive history of that murky 300 year-period that spanned either side of the traditional divide between Roman Britain and Anglo-Saxon England or, in less parochial terms, between antiquity and the early middle ages. In many ways it was a really admirable project, but Morris was suffering from ill-health (he died in 1977, halfway through translating the History of the Britons) so he completed in a rush and ended up mixing his own nuanced interpretations of the scanty contemporary textual records with those of the larger quantity of literature written in the ninth century and later. His own experience of WW2 strongly shaped his history, leading him to shift all focus away from the Anglo-Saxons and onto the Romano-Britons and their struggle against them. For example, on p114 he wrote

"Badon was the ‘final victory of the fatherland’ [Gildas, of course]. It ended a war whose issue had already been decided. The British had beaten back the barbarians. They stood alone in Europe, the only remaining corner of the western Roman Empire where a native power withstood the all-conquering Germans. Yet the price of victory was the loss of almost everything the victors had taken arms to defend."

Morris took King Arthur's existence as a historical fact and like Skene, Rhys, Lloyd, Collingwood and so many other scholars before him, he imagined him as a supreme commander of the Romano-British field armies who led them to victory over the Saxons in all the battles mentioned in the History of the Britons. After he saved southern England from the Germanic invaders, Arthur was, according to Morris on p 116:

"A just and powerful ruler who long maintained in years of peace the empire of Britain, that his arms had recovered and restored. Contemporary and later writers honour and respect the government he headed. A few notices describe events and incidents that happened while he ruled. None describe the man himself, his character or his policy, his aims or his personal achievement. He remains a mighty shadow, a figure looming large behind every record of his time, yet never clearly seen."

Thus in the years around 1970, it appeared that there was at last a growing consensus among historians and archaeologists alike behind the existence of a historical King Arthur. As the twentieth century entered its last quarter, however, the tide turned against the idea of a historical Arthur, in academic circles at least. In 1975, the same year that Monty Python and the Holy Grail debuted in cinemas all over the United Kingdom, so began the scholarly counter-attack against the historical King Arthur.

James Campbell, one of my favourite historians, was characteristically kind and generous about John Morris' book. In the review he wrote in 1975, he called it "brave, comprehensive and imaginative", but then went on to write that Morris had clearly let his imagination get the better of him and that the book inhabited a space beyond what the actual evidence would allow. David Dumville, a leading Celtic scholar renowned for treating all written sources from early medieval Britain with maximum scepticism (he's also the main guy responsible for us no longer attributing the History of the Britons to Nennius), was much more acerbic. In his article 'Sub-Roman Britain: History and Legend', History (1977), pp 173 - 192, Dumville argued that they had been completely misled by the written sources from the ninth century and later. In his view, these sources have no value as historical evidence for what was going on in the fifth and sixth centuries at all. And on the matter of a historical King Arthur, he made the following forthright statements (pp 187 - 188):

Arthur [is] a man without position or ancestry in pre-Geoffrey Welsh sources. I think we can dispose of him quite briefly. He owes his place in our history books to a ‘no smoke without fire’ school of thought ... The fact of the matter is that there is no historical evidence about Arthur; we must reject him from our histories and, above all, from the titles of our books.

These two pages and the stringent comments made therein would, with almost immediate effect, decisively tip the scales against the historical King Arthur. Symptomatic of it all was how Michael Wood's In Search of the Dark Ages documentary series for the BBC from 1979 - 1981, a real landmark of cultural television (my mum remembers watching it as a kid), took the same sceptical approach to the existence of a historical King Arthur, which got Michael Wood some hate mail from Arthurian enthusiasts. A substantial number of academic historians, including Wendy Davies. Oliver Padel and Nicholas Higham, followed Dumville's lead. Indeed, Arthur denialism has become more and more in vogue since the 1980s as the very idea of fifth and sixth century Britain as an age of warfare between Saxons and Romano-Britons, or indeed the very idea of an Anglo-Saxon migration at all, has come under fire from some scholars. As you might know from my previous post, I do not sympathise with these views.

At the same time, the historical Arthur ain't dead yet. Outside academia, dozens of amateur scholars and self-appointed experts have, in the last forty years, have written books outlining their own particular vision of a historical King Arthur, even trying to pinpoint him to specific dates and places, and the reading public have lapped them up. I hate to be cynical, but the truth is, King Arthur sells. Probably the best comments from a non-academic historian on the matter of Arthur's historicity have to be from Terry Deary in his Horrible Histories: Smashing Saxons (2000), a book I remember enjoying back when I was 7:

"The Saxons were battering the Brits, but some Brits started fighting back. They wanted a Britain the way it was in the old Roman days of eighty years before. One leader managed to win forty years of peace. He was called ‘the last Roman’ and his name was Arthur. Five hundred years after Arthur died his name was remembered and storytellers came up with some great tales of Arthur’s deeds. Ina word they were bosh. In four words they were total and utter bosh. Any historian will tell you."

Most academic historians actually fall into what we can call the Arthur agnostic camp. Among them are Thomas Charles-Edwards, Christopher Snyder, Guy Halsall and Chris Wickham. Emblematic of this is position is Thomas Charles-Edwards' passing comment back in 1991 that "one can only say that there may well have been a historical Arthur; that historian can as yet say nothing of value about him", which is basically echoed almost verbatim in Chris Wickham's The Inheritance of Rome: A History of Europe from 400 - 1000 (2009) and Guy Halsall's Worlds of Arthur: Fact and Fiction of the Dark Ages (2013). Snyder says something similar, but also adds, as a deliberate riposte to Dumville, "so much similar evidence, circumstantial though it may be, must have some cause, and its hard to see the 'fire' as the tale of one creative medieval bard."

As of 2022, the issue is still far from settled, and our knowledge of what the hell was going in the fifth and sixth centuries in these Isles is forever expanding, especially in light of archaeology. Maybe we'll have a definitive answer sometime ...

And well that's the story of the debate. But now you'll be asking "But Joe, we came here to hear your view on King Arthur, not those of other historians for the last millennium." I apologise for having gone on at length and gone into digressions (these are my great flaws as a historian and communicator), though unfortunately all of this was necessary to set it up. But at last, here we are ...

Do I think King Arthur was real ...

Broadly speaking, approaching this as a historian I'd say I'm in the Arthur agnostic camp, though at a sentimental level I'm very sympathetic to the idea of a historical Arthur existing. Labels like "Arthur agnostic" are more than appropriate because a certain level, the King Arthur debates stops being a historical debate and essentially becomes philosophical. King Arthur sceptics have often brought up Russell's teapot, an analogy for the existence of God created by the atheist mathematician, philosopher and activist Bertrand Russell (1872 - 1970). Its premises are as follows:

- A man claims there is a teapot orbiting the sun between Earth and Mars - it is too small for us to see by telescope and since we can't journey out to space (Russell was writing in 1952), there's no way of proving that its not actually there.

- Russell's hypothetical man says "ah, since you can't prove the teapot isn't there, you must assume it is there."

- Such a proposition is, of course, ridiculous - why must we believe in this teapot just because we can't prove it isn't there?

- Therefore, proposes Russell, the burden of proof must lie with the person making the positive claim (that the teapot exists) rather than with the sceptic.

Russell wrote this analogy about the existence of God, arguing that the burden of proof lies with the religious believer, but it really isn't hard to see how its logic applies to King Arthur's existence as well. Indeed its there, explicitly or implicitly, in the arguments of most King Arthur denialists. And unlike God, Arthur can't protest in his favour to have created the universe, be the bedrock of an entire ethical system (you really can't say the same about Arthur and chivalry, and actual medieval chivalry really is dead now) or give billions of people their sense of meaning and purpose in the world.

I would respond to that kind of argument with another quasi-philosophical position, that being "well you can't prove a negative either." Since there's nothing inherently ridiculous or implausible about King Arthur, once stripped of all the anachronistic twelfth century mythology, we can't rule him out. After all, we have next to nothing in terms of written sources for what was going on fifth and sixth centuries, to the point its basically impossible to write any kind of continuous history of political events in this period, much as some, like John Morris, may have tried to. We simply do not know enough about the period to say definitively that Arthur could not possibly have existed.

To really reach back to my A level Philosophy classes, I'd also bring in the problem of induction. The classic example of it is the black swan - traditionally, it was axiomatic that all swans were white until a Dutch sailor discovered a black swan in Western Australia in 1697. Like natural scientists, we as historians are always faced with the very real possibility that new material, written or archaeological, may be discovered that might either challenge our current assumptions or give support to previously discredited ideas. For example, around 1870 the consensus amongst Classicists and ancient historians was that the siege of Troy was just a myth and the city of Troy never existed. That all changed when Heinrich Schliemann, a German businessman turned amateur archaeologist, found the site of Troy, at Hisarlik in Turkey, and excavated it in 1873. Then in the twentieth century scholars found the Tawagalawa letter (dated to c.1250 BC), a piece of official correspondence between a Hittite king and a king of Ahhiyawa (Achaea, home of the Mycenaean Greeks). In this letter, the Hittite king writes "Now as we have come to an agreement on Willusa over which we went to war." Willusa is remarkably similar to the ancient Greek name for Troy, Ilion, and modern scholars have argued it to be in the same location as the site excavated by Schliemann. Thus many modern scholars now think that the Trojan war did happen, though most, or all, of the exact details were distorted and embellished in subsequent oral accounts between the late Bronze Age and when Homer (or whoever he really was) sat down to write it in the eighth century BC. Funnily enough, as late as 1900, virtually nothing was known about the Hittites at all - what we now know about Hittite civilisation is thanks to the miracle of twentieth century archaeology.

.

|

| Homer wasn't a liar after all: the Tawagalawa letter (thirteenth century BC) |

A similar story goes with the Viking discovery of North America. Until the 1960s, some scholars thought that the westwards voyages mentioned in the Vinlandsaga, written sometime between 1220 and 1280, were just fanciful tales. From 1960 - 1968 however, archaeologists Helge Ingestad and Anne Stine Ingestad discovered a Norse settlement dating to the first quarter of the eleventh century at L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada. Now most modern scholars accept that the Vikings did indeed settle in the North American mainland, if only very briefly.

|

| The reconstructed Norse longhouse at L'Anse aux Meadows |

I suspect that the same may well hold true of King Arthur as well. Perhaps some sixth century Romano-British text that has survived by pure chance somewhere will be found, confirming the existence of a British dux bellorum called Arthur who fought battles against Saxon warlords. Or maybe another archaeological discovery like the one at South Cadbury, but on an even grander scale, will be found, that will well and truly convince us that the Romano-Britons were at one point unified under a really powerful, charismatic, supreme leader who could just about fill in an Arthur-shaped mould.