This began its life as a facebook post I did last summer, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests following the killing of George Floyd on 25 May 2020. I thought I should include it here because its still very topical and so I thought it deserved viewing from more than just my friends on social media. At the same time, I don't want to oversell myself on this - I am by no means an expert on this particular area - most of the secondary literature on race and otherness in the Middle Ages (in this context essentially meaning the later medieval period/ post-1100), I must confess, I have not read and have only cursory familiarity - and this post was very much cobbled together from what bits and bobs I knew and had read around about the topic.

Black Africans and the European Middle Ages

In the midst of the current discussions on institutional racism and inequality both in the US and over here, history seems more relevant than ever. Naturally, most of the discussion has focused on Early Modern (c.1500 - 1800) and Modern (post-1800) History - the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and its eventual abolition, the American Civil War and Reconstruction, the European colonisation of Africa, segregation in the USA, the Windrush generation and their enduring legacies in the present age. Attention has also been drawn to the contributions of black people to Western civilisation, with figures like Joseph Boulogne "The Chevalier de Saint Georges" (1745 - 1799), the great Afro-Caribbean French classical composer. and Katherine Johnson (1918 - 2020), the Afro-American mathematician responsible for getting Neil Armstrong on the moon, amongst others getting the recognition that they've always deserved but has often been denied to them.

As some of you already know, I am of course not a modern historian. The time period I work on, the European Middle Ages, may seem to many like it has very little relevance to all this. Many people today still see globalisation as something that began in the 1490s with the voyages of Christopher Columbus to the Americas and Vasco da Gama round the Horn of Africa to India, while viewing the Middle Ages as being largely a period of minimal connectivity with most cross-civilisational contacts being violent i.e. the Arab conquest of Spain, the Crusades, the Mongol invasions etc. That view is being revised, as now we're coming to appreciate just how economically and culturally connected the medieval world, especially in the Central Middle Ages (950 - 1350, my favourite bit) really was. The economic connections is not what I'll primarily concern myself with here, but they were definitely there. By the 13th and 14th centuries, West African ivory was being used in all manner of different forms of Western European craftsmanship such as medallion of the attack on the castle of love from early 14th century France (see first image), and French copper was being used to make bronze sculptures like this rather naturalistic one from the kingdom of Ife in modern-day Nigeria (see below). Medieval western Europeans were definitely well aware of the wealthy, powerful and hugely sophisticated states in Sub-Saharan Africa from whence their gold and ivory came. The Catalan World Atlas of c.1375, a remarkably detailed and geographically accurate map compiled by the Catalan Jewish geographer Abraham Cresques for King Charles V of France (reigned 1364 - 1380), depicts (also see below) south of the Sahara a resplendent African king who could possibly be identified with the famous Mansa Musa (1280 - 1337), emperor of Mali, who was so wealthy that when he went on pilgrimage to Mecca he caused an economic crisis in Egypt from the hyperinflation created by his generous charity to the poor there.

So goods made their way across continents, but what about people? Contrary to what you might think, the story of (black) African migration to Britain does not begin with Windrush or even with the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Rather, it begins in Roman Britain as Moorish (possibly black) legionaries were stationed on Hadrians' Wall in the reign of the African emperor Septimus Severus in the early 3rd century and the skeletons of men and women of black African descent have been found in London and York. Yet perhaps that's to be expected - Ancient Rome was, after all, a vast cosmopolitan empire stretching from the Pennines to the Euphrates and from the Danube to the Sahara.

What about after the Western Roman Empire abandoned Britain in the early 5th century? Well it seems that while Roman imperial authority disappeared from Britain at that time, and the Roman way of life largely evaporated not long afterwards, connections with the Mediterranean and the world beyond did not. Excavations at the Romano-British fortress of Tintagel in Cornwall (often thought to be the real-life Camelot of Arthurian legend) and the Anglo-Saxon burial site at Sutton Hoo in East Anglia, have shown that trade with places as far away as North Africa and the Middle East did continue into the "Dark Ages", if only on a reduced scale and to satisfy the demands for luxury goods of elites - Romano-British warlords, early Anglo-Saxon kings and their warrior retinues. As with regard to people, it seems that lowland Britain in the "Dark Ages" was more ethnically diverse than just Romano-Britons, Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians. If you read the Venerable Bede's (died 735) "Ecclesiastical History of England", our foremost source for the 7th and early 8th centuries, you may encounter Abbot Hadrian of Canterbury (died 709). According to Bede, Hadrian did much to improve the organisation of the early English church as well as well as establish a school of Ancient Greek at Canterbury - besides a few enclaves in Italy, Greek was rarely studied in the early medieval West, so this was a very rare contribution yet an invaluable one to furthering Christian learning in Anglo-Saxon England. Bede describes Hadrian as a man of "African race." Since Bede was likely referring to the Roman province of Africa, this means Hadrian probably came from modern-day Tunisia. Whether Abbot Hadrian was what we'd now describe as black (black and white were not ethnic groupings in the early medieval period, after all) is uncertain and he may have more likely been a Berber, yet that would have still made him what we'd now consider to be BAME/ POC.

Further evidence of black Africans in Anglo-Saxon England comes in the form of a skeleton found at Fairford in Gloucestershire dating from sometime between 896 and 1025, around the time of the struggle against the Vikings. Forensic anthropological analysis has shown that this skeleton was that of a woman from Sub-Saharan Africa. Sadly, we don't know enough to figure out her social status and how she go there. Given that the Vikings raided as far as Islamic Spain, where black Africans lived along with Muslim Arabs, Jews and Christian Spaniards, its possible that she might have been a slave - early Irish sources indicate that the Vikings brought back some African slaves to their capital at Dublin - but we shouldn't assume that either, since traders and diplomats from Islamic Spain and North Africa are known to have visited the British Isles in that period. Going into the Central Middle Ages, a skeleton has been found in the cemetery of a Franciscan Friary at Ipswich in Suffolk of a black man, dated somewhere between 1258 and 1300. It seems likely that he came there with Robert Tiptoft, the nobleman who had founded the friary, as Robert had been on the crusade of the French king, Louis IX (1214 - 1270), to Tunis in 1270 and is recorded has having brought back four "captive Saracens (Saracen is a term normally used to refer to Arabs, but it came to refer to any non-Christian people i.e. the pagan Lithuanians were referred to as "Saracens" by crusader knights in the 14th century Baltic)." At the same time, we can't be sure if that man was one of those Muslim captives - he may have been a Christian from Nubia (modern day Sudan), an area often allied quite closely with Western crusaders. And certainly he was quite well-respected, of high status and, by the time of his death, baptised given that he was given the honour of being buried in the friary precinct. A final example to give, from the close of the Middle Ages, would be that of John Blanke, a "blackamoor" trumpeter in the retinue of King Henry VII who then went on to serve his son Henry VIII and successfully petitioned him for his wages to be doubled, showing that his music was clearly very appreciated at the Tudor court (the fourth image is of John Blanke as depicted in the Westminster tournament roll).

So clearly there were black Africans in Medieval Britain and Europe, but what were medieval attitudes to race like? This is a complicated matter, not least because the Medieval Western sources give us very different impressions depending on their authorial, historical and cultural contexts. Its safe to say that medieval people didn't have the same racial conscience that we do (they certainly didn't see the world as being divided up into whites/ caucasians, blacks and East Asians) and that the modern scientific racism that was to emerge in the wake of European colonialism in the 18th and 19th centuries didn't exist yet. At the same time, medieval Europeans weren't colour-blind (except for in the medical sense, no one is really) and as recent scholars, especially American ones, have been keen to point out, there are a sizeable number of works of (mainly post-1300) medieval art and literature in which black Africans are depicted as exotic and Orientalised others if not savage and monstrous ones. Its important to remember that despite what has been said earlier here, seeing a black person would not have been an everyday experience for most medieval Europeans save for those who lived on frontier zones with the Muslim world - Iberia, Sicily and the Crusader States. Black people would have, in many contexts, been associated with Islamic polities hostile to Western Christian powers - large contingents of the armies of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt and the Almohad Caliphate in Spain, great rivals of Western crusaders, would have consisted of black slave troops. There was also an ancient association of the colour black with sin and the devil, going back to the Roman poet Paulinus of Nola in the early 5th century AD and the Epistle of Barnabas (written sometime between 70 and 132 AD).

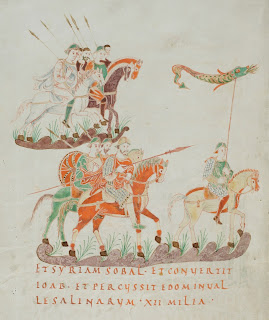

But medieval European attitudes to black Africans were nowhere near all ones of exoticism and bigotry. Lets consider some examples here, from a topic very close to my heart. As some of you know, I've always loved knights, castles and chivalry. So lets consider some depictions of black African knights from the Holy Roman Empire under the Hohenstaufen dynasty, which ruled the Empire from 1152 to 1245. To give just a little bit of background, the Hohenstaufen emperors frequently clashed with the papacy for who should have (almost entirely theoretical) supreme authority in Christendom as well as the more practical issue of who had the right to appoint bishops in Germany, and also with rebellious German dukes and Italian city republics. The second Hohenstaufen Emperor, Henry VI (died 1197), married Constance, the heiress to the Norman kingdom of Sicily. Their son, Frederick II (1194 - 1250), spent most of time in Sicily and there he ruled over a cosmopolitan kingdom in which black Africans alongside Greeks, Arabs, Jews and of course Germans and Italo-Normans all held positions of honour at his court and were amongst his retinue. Since Frederick II wanted to promote the image of himself as the heir to the ancient Roman emperors (see image below for a coin of his, likely produced with West African gold since Frederick began minting gold coins, being the first Western European ruler since the 8th century to do so, after he sided a trade deal with the Sultanate of Tunis, a depot for West African gold, in 1231), the presence of black Africans in his empire symbolised how, like Augustus Caesar before him, he was bringing all of humanity together so that they might enjoy universal peace and prosperity (see below a fresco Frederick had commissioned at Verona in the 1240s depicting his various subjects who, apart from their headgear, dress alike). In the reign of Frederick II, a statue was erected at Magedburg Cathedral depicting St Maurice (also see below). This indicates that Frederick had no interest in portraying the black Africans in his empire as fundamentally other, but rather as his lawful subjects along with all other peoples, sharing a common humanity.

Towards the end of Frederick II's reign, a statue was commissioned for the cathedral at Magdeburg in Saxony. It depicts St Maurice, the patron Saint of the Holy Roman Empire since the reign of Otto I (936 - 973). St Maurice was a 3rd century AD Roman soldier and early Christian martyr from Egypt. Here he is depicted unambiguously as a black African man though in relatively naturalistic way and not as a derogatory character. Instead, he is presented as a heroic and admirable figure, clad and equipped as mid-13th century German knight.

This nicely ties in with the final example that we shall now look at, drawn from the works of one of the most celebrated poets of Hohenstaufen Germany, the knight Wolfram von Eschenbach (died 1230). He is famous for the epic poem, Parzifal, the story of King Arthur's grail-questing knight based on an earlier, late 12th century Old French version. Here he tells of how the father of Percival, Gamuret, a knight of Anjou (a region of North West France), ventures through the Middle East to Africa down to the kingdom of Zalamanke. Here he comes to the rescue of the black African queen Belkane, who is being besieged by the king of Scotland. Afterwards he is received at her court with honour and despite their racial and religious differences (Belkane is a pagan who appears to worship Juno and other Graeco-Roman gods) Gamuret falls in love with her, finding Belkane to be beautiful and as pure-hearted as any Christian woman, and so they engage in a passionate love affair which produces a child - Feirefis. Gamuret has to return to Anjou and there fathers with another woman his other son Percival.

Percival later meets his mixed-race brother Fierefis and they do battle. They are both impressed by each other's chivalry, reflected above all in their martial prowess and courtesy, and they soon realise that they both share a common heritage. Eventually, Fierefis is taken to King Arthur's court and the poem follows thus:

"And Feirefis sat by King Arthur, nor would either prince delay

To the question each asked the other courteous answer to make straightway –

Quoth King Arthur, ‘May God be praised, for He honoureth us I ween,

Since this day within our circle so gallant a guest is seen,

No knight hath Christendom welcomed to her shores from a heathen land

Whom, and he desired my service, I had served with such willing hand!

Quoth Feirefis to King Arthur, ‘Misfortune hath left my side,

Since the day that my goddess Juno, with fair winds and a favouring tide,

Led my sail to this Western kingdom! Methinks that thou nearest thee

In such wise as he should of whose valour many tales have been told to me;

If indeed thou art called King Arthur, then know that in many a land

Thy name is both known and honoured, and thy fame o’er all knights doth stand.’

(529-540)

And Arthur willed ere the morrow a banquet, rich and fair,

On the grassy plain before him they should without fail prepare,

That Feirefis they might welcome as befitting so brave a guest.

‘Now be ye in this task not slothful, but strive, as shall seem ye best,

Then henceforth he be one of our circle, of the Table Round, a knight.’

And they spake, they would win that favour, if so be in it should seem him right.

Then Feirefis, the rich hero, the brotherhood with them aware;

And they quaffed the cup of parting, and forth to their tents would fare.

And joy it came with the morning, if here I the truth may say,

And many were glad at the dawning of a sweet and a welcome day.

(653-662)"

All throughout the poem, Wolfram von Eschenbach plays those ancient tropes associating blackness with sinfulness and then subverts them to show that what matters is not the colour of your skin but the hue of your soul, which is determined by your own free-willed decisions. He also demonstrates, like the statue of St Maurice, that men of all races can belong to the order of chivalry and be held in honour and respect by all knights, even if they are not baptised Christians, as is clearly the case with Fierefis. Its worth mentioning that there were other non-white knights of the Round Table, such as the Moorish knight Sir Morien and the Arab knights Sir Safir, Sir Palomides and Sir Segwarides. The Arthurian legends have in many of their more modern re-iterations that we're more familiar with of course been whitewashed, but next time you here someone complaining about POC actors being cast in a movie or TV series about King Arthur as "political correctness gone mad", as indeed happened with the recent "Merlin" TV series which I'm sure many of us remember (I was a fan of that series), tell them that the original medieval Arthuriana (and indeed medieval Britain historically) was much more diverse than they think.