Its extraordinary to think of what's transpired in British royal history in the last year - a Platinum Jubilee (the first ever in British history and quite possibly the last), the funeral of a Queen and now a Coronation (the first in 70 years). And so far I haven't said anything about them here. But now, as a historian who is very much into the history of monarchy, religion and elite ritual, I feel like I should say something. My interest in such things is not exclusively historical. I am a quiet royalist - I support the British monarchy, but I'm not ostentatious or obsessive about it. You certainly wouldn't have found me camped out on the Mall this morning. I don't even have a favourite royal, and there's plenty of members of the royal family I dislike. I don't think they're perfect or beyond criticism. But I see our constitutional monarchy as infinitely better for the UK than a republic. And even as an agnostic I have no objection to having a head of state that (notionally) appointed by God to rule over us, just like I have no objection to the Church of England existing.

|

| Bit boring I know, but I don't want any journalists suing me for copyright. So I had to pick this. |

But personal opinions aside, I think the coronation is very interesting from a historical perspective. Like the present monarchy itself, its a mixture of old and new. There are many elements of Charles' coronation that are new. One of the things I noticed when I was watching it on TV was the multi-faith element. There was a small Greek Orthodox choir singing, no doubt a nod to King Charles' late father, the Duke of Edinburgh. Charles was attended on not just by Anglican bishops but also by a Catholic cardinal, a Greek Orthodox bishop and representatives of the Jewish, Muslim, Hindu and Sikh communities in the UK. This no doubt reflects two things. First is Charles' own desire to be seen not as Defender of the Faith but Defender of Faith. This is of course at odds with the very coronation oath he swore today, which has remained unchanged since 1689 when the Glorious Revolution made it a requirement for all future monarchs to uphold the Protestant faith. The second is the changing nature of British society has forced the monarchy to adapt with it. Its debatable how religious the British really were in the 1950s, and secularisation was undoubtedly already underway. About 3 million people out of a population of more than 41 million in England regularly took communion in an Anglican church, down by more than 500,000 from 1935. Other Protestant churches were also suffering decline, though Roman Catholics were more stable. But census data shows by far the majority of the population still identified as Christian when Queen Elizabeth II was crowned, even if most of them only attended church services irregularly. Cultural Anglican Christianity was very strong indeed i.e., in music Benjamin Britten, in art Graham Sutherland and Stanley Spencer, and in literature T.S Elliot and C.S Lewis. And though the first mosque in the UK had been built in Woking, Surrey, in 1889 there were no more than a few hundred Muslims, Hindus or Sikhs in the UK. Now, thanks to 70 years of post-imperial immigration and the changes that followed the cultural revolution of the 1960s, this is very different. Now, as of the 2021 census, only 46.2% of the population of England and Wales identify as Christian, a 13.1% drop from 2011. This makes it the first time in British history since the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons in the seventh century that less than 50% of the population has identified as Christian. And among those born after 1980, the percentage of Christians who are Roman Catholics in England and Wales is equal to or exceeds those who are Anglican Protestants, for the first time since the reign of Elizabeth I. And while Anglican church attendance has decline by 9% in the last decade, Pentecostal church attendance has gone up by 50% thanks, in large part, to Nigerian immigration. And now more than 37% of England and Wales' population have no religion, a rise of 12% from 2011. It has been for this third of population that the deeply religious nature of the coronation ceremony has been most controversial, indeed downright offensive to the sensibilities of some. And about 10% of the population of England and Wales identify as members of a non-Christian religion (approximately 6% Muslims, 2% Hindus and 2% Jews, Sikhs, Buddhists and other religions respectively). The remaining 6% of the UK population refused to say what their religious beliefs were. Having lived in southwest London all my life, I'm reminded of this religious diversity almost every day. So by including those multi-faith elements in Charles III's coronation, the monarchy was acknowledging that the UK in 2023 is not the Protestant Christian nation it still essentially was in 1953.

The music likewise reflects change as well. I absolutely love Handel's Zadok the Priest, that's been a staple tune of all British royal coronations since the coronation of George II as king of Great Britain and Ireland in 1727. And I don't mind Elgar. But it was good to see Greek Orthodox acapella, a Gospel Choir and Andrew Lloyd Webber added to the mix for the first time ever. My mother also pointed out how a significant portion of the choristers in Westminster Abbey were female. This would not have been the case in 1953, as girls' choirs were not permitted by the Church of England until Salisbury Cathedral in 1991 took the progressive decision to allow them, allowing more opportunities for female musical talent to be recognised than had previously been available.

Indeed, its fair to say that the monarchy, much as it tries to appear timeless and unchanging, really does change a lot both with each individual monarch, who has their own style of kingship/ queenship, and with the general direction of travel of British politics, society and culture. I won't go into every detail of the history of English/ British royal coronations in the last 1100 years. That would take forever, and the Church of England has produced a full historical commentary on the coronation service. But what I will talk about is what I'm qualified to talk about as an early medievalist. Namely the aspects of English royal coronations that are still recognisable from how they were more than a thousand years ago.

Coronations haven't everywhere and always been a part of monarchy. While Egyptian pharaohs and the Biblical kings of Israel were crowned, coronations were never a part of "European" monarchical traditions until the later Roman Empire. In the late third century, after decades of constant mutinies in the legions, civil wars, assassinations and coups d'etat, the Roman emperors stopped pretending notion that the Republic was somehow still going, just under a different kind of management, were only princeps ("chief citizen"). It was from this point on they started to embrace a visibly royal style more similar to what had existed in the Near East for thousands of years, and indeed what we think of when we think of royalty today, and crowns were part of it. Emperor Aurelian (r.270 - 275) was the first to wear a diadem, and by the time of Constantine it had become part of the regalia - the symbolic objects a legitimate emperor needed to possess. The first Roman emperor to receive a "coronation" was Julian in 361 when, according to the soldier and historian Ammianus Marcellinus, the emperor was lifted by his troops up onto a shield and a diadem was set upon his head. After Christianity had become the state religion of the Roman Empire in 381, the ecclesiastical element started to feature, but only in the East - in the fifth century, Eastern Roman emperors began to be crowned by the patriarchs of Constantinople, but the pope did not do the same for their western counterparts.

In the post-Roman kingdoms, it doesn't seem like coronations were much of a thing in the sixth and early seventh centuries. Kings were acclaimed and raised up onto a shield, just like Roman emperors had been before them, but they weren't crowned. Kings had other special markers of royalty. The Merovingian Frankish kings had their luxurious long hair and chariots drawn by oxen, and early Anglo-Saxon kings had royal helmets i.e., the helmet which may or may not have belonged to King Raedwald (d.628) of East Anglia at Sutton Hoo. But in Spain, the Visigoths started a new trend - the earliest Visigothic king who we know for sure was crowned was King Sisenand in 631. Then in 672, with the accession of King Wamba (r.672 - 680), the Visigoths started a new trend - the anointing of kings. This is a practice that was literally as old as the Bible. Indeed, Handel's Zadok the Priest we heard played today refers to none other than the anointing of Solomon as king of Israel. But after the fall of the ancient kingdom of Israel, anointing ceased to be a part of kingship anywhere in Europe or the Mediterranean until the Visigoths revived it. Or is that quite so. Around 700 AD, a monk called Adomnan of Iona described how St Columba had, back in the 560s, anointed a number of Irish kings. Anyway, whether we can call it a Visigothic or an Irish invention, anointing was a very new thing in the sixth and seventh century West, and other countries were slow to catch on. But it was highly significant all the same as it could be used to establish that a monarch's legitimacy, like that of Solomon as king of Israel, came directly from God. The origins of divine right begin here. Indeed in both 1953 and 2023, the anointing of Elizabeth II and Charles III respectively were deemed too sensitive to be shown on television.

The people who really cemented anointing and coronations as a widespread feature of European monarchy that has endured to the present day are none other than my favourite people - the Carolingians. I've written here before about the coronation and anointing of Pippin the Short in 751 and his reanointing in 754, and I'm not going to do so again. Likewise, I won't revisit the coronation of Charlemagne. Indeed its generally thanks to the Carolingians that most of our western ideas of what king looks like really solidifed and became embedded - they pioneered the use of orbs and sceptres as well. While sadly we've got no film footage of Carolingian coronations, we have the second best alternative - detailed scripts and choreographies written by Archbishop Hincmar of Rheims (806 - 882). Hincmar wrote them for the West Frankish king Charles the Bald's coronation at Metz as king of Lotharingia in 869 following the death of nephew, King Lothar II. In total, Charles the Bald went through four coronations in his fifty-six years of life; that's one hell of a lot of coronations.

Hincmar describes how Charles the Bald was firstly blessed by the seven bishops present - Adventius of Metz, Arnuld of Toul, Hatto of Verdun, Franco of Tongeren, Hincmar of Laon (Hincmar's own nephew), Odo of Beauvais and Hincmar of Rheims himself. Then Hincmar said "May the Lord Crown you" and anointed Charles the Bald on his forehead with a chrism of holy oils. Then Hincmar gave more blessings before instructing his colleagues to set the crown of Lotharingia on Charles's head. After this Charles was given the sceptre before Hincmar gave the final blessing "May the Lord give you the will and power to do as He commands, so that going forward in the rule of the kingdom according to his will together with the palm of continuing victory you may attain the palm of eternal glory, by the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ." Finally, there was a mass and King Charles the Bald took communion bread and wine from the bishops, before Hincmar ended the service with a prayer for God to protect the new king and give his soul a place in Heaven.

In all of the basic outlines of the service, the coronation service that Hincmar organised and performed for King Charles the Bald in 869 is not at all different to that which Justin Welby did for King Charles III in 2023. The Carolingian legacy undoubtedly lives on in the modern British monarchy, not least in that we have kings called Charles.

After the collapse of the Carolingian Empire, we see further moves towards royal coronations as we know them today. Widukind of Corvey gives us a detailed description of Otto the Great's coronation as King of Germany in 936. He describes how Otto was presented with the sword "with which you may chase out all adversaries of Christ, barbarians and bad Christians, by the divine authority handed down to you and by the power of all the empire of the Franks for the lasting peace of all Christians." Then Otto was given the bracelets and cloak and was told "these points falling to the ground will remind you with what zeal for the faith you should burn and how you ought to endure a preserving peace to the end." Next he was given the sceptre and staff and reminded of his kingly duty to protect all the churches, widows and orphans in the kingdom and to be merciful to all his subjects. the bishops of Mainz, Cologne and Trier then anointed and crowned Otto the Great, and he sat on the throne of Charlemagne. The giving of the bracelets and the sword, which weren't part of Carolingian coronations and were thus fairly new to Otto the Great's coronation, are now part of British royal coronations, as we saw on television today.

How did these Continental ideas come to England. The answer is that Aethelstan, the first ruler of a united kingdom of England brought them over. Aethelstan had a lot of continental connections. His sister Eadgyth married none other than Otto the Great in 929. His other sister, Eadgifu, married King Charles III the Simple of West Francia, the grandson of Charles the Bald and namesake of our current king. And after Charles III was deposed and imprisoned following the battle of Soissons in 923, his son Louis IV went to live with his uncle, Aethelstan, in England. So Aethelstan knew a lot about continental kingship. Aethelstan therefore decided in 925 not to be acclaimed king and presented with the royal helmet but to be acclaimed, anointed and crowned as king, following continental practice. And this happened at Kingston-upon-Thames, bang in my local area. The first coronation we know about in detail, however, was that of his grandnephew Edgar the Peaceful at Bath in 973. It was Edgar's coronation that really set the ball rolling for later coronations, including that of our present king. The coronation thus really is the only aspect of the British monarchy where there's any meaningful continuity between its tenth century beginnings and the twenty-first century institution we know today.

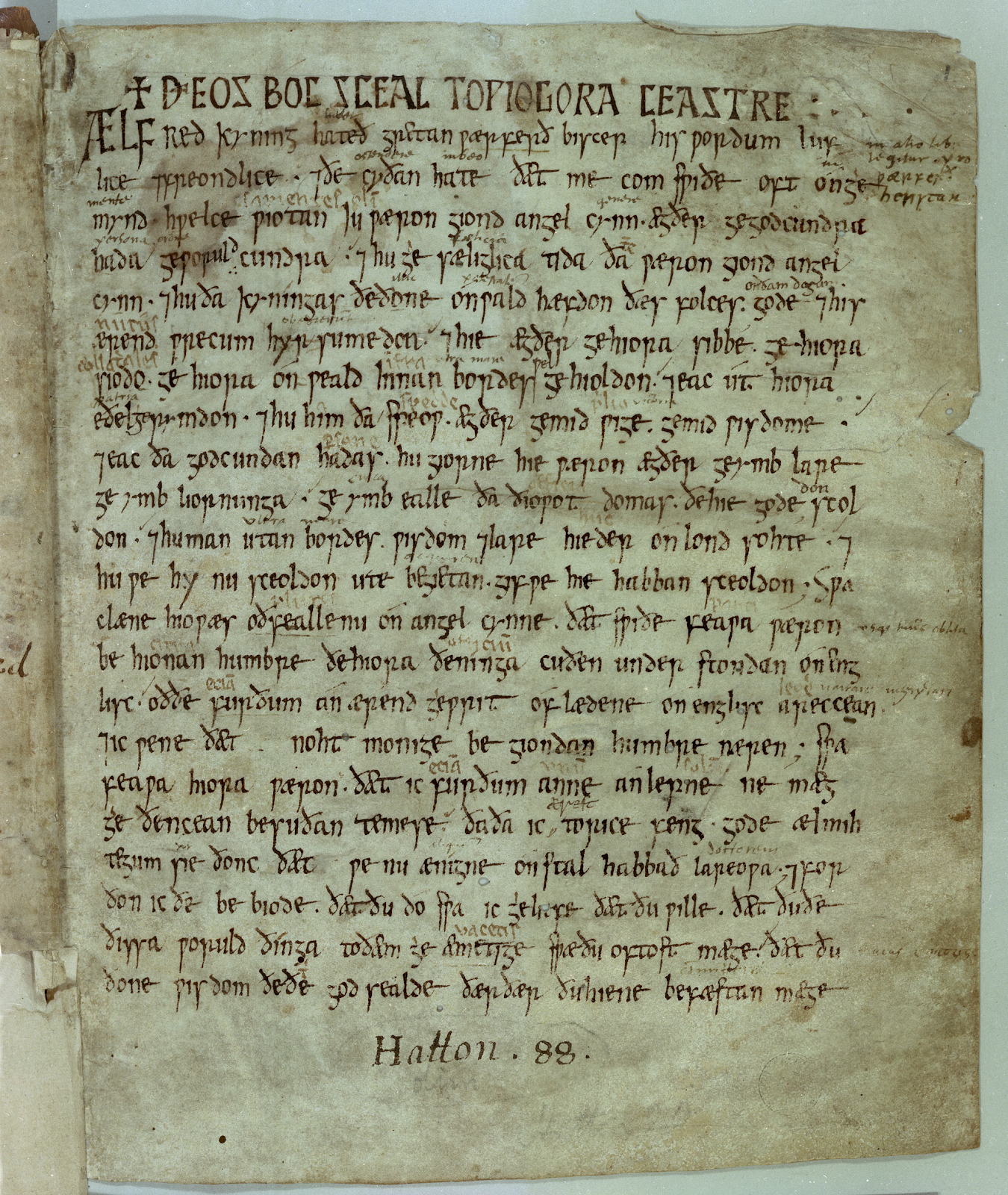

|

| King Edgar on the frontispiece of the New Minster Charter, made in 966. |

And that is the end of my potted history of the early medieval origins of British royal coronations. I hope you've enjoyed it.