As background to my series' on the last Carolingian kings (starting with the mini-series on Charles the Simple) and ton the Ottonians, I am going to make a post about a certain event that happened 1178 years ago (the exact date is not known, but it took place in the month of august) at a certain place in what is now the Lorraine region of eastern France.

The Long backstory

On Christmas day 800, Charlemagne, king of the Franks and Lombards, was crowned Roman emperor in the West by Pope Leo III in St Peter's Basilica in Rome. This was literally the crowning glory to three decades of near constant political and military achievement, in which the Franks had acquired an empire comprising essentially the original six nations of the European Economic Community (the forerunner to the EU) - France, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, West Germany and Italy - plus a few other areas, namely modern day Switzerland, Austria and Catalonia. This made Charlemagne's empire the largest political unit Western Europe had known since the collapse of the old Western Roman Empire in the fifth century. In many ways this might have seemed to have ushered in an exciting new era. Charlemagne set to work at building an imperial capital at Aachen replete with an imperial palace, whose chapel (the only bit that survives today, see image below) was modelled on the architectural styles prevalent in the still surviving eastern half of the Roman Empire (what modern historians choose to call the Byzantine Empire) and was constructed with classical Roman columns brought over from Italy. In 802, he made all free men over the age of 12 in the realm swear an oath of loyalty directly to him - an unprecedented display of authority which must have required some very concerted administrative effort -and doubled down on an ambitious programme of governmental, ecclesiastical and moral reform. In the meantime, as part of his ideology of Roman imperial renewal, an ambitious revival of classical literature, art and education took place - what modern historians call the Carolingian Renaissance.

Still, not everything was looking great. This was about the point in time the Vikings were starting to make a nuisance of themselves, and Charlemagne's ambitious reform programme was all the more necessary (and some would say all the more futile) as complaints about corruption, maladministration and the oppression of the poor by the powerful were mounting. And then there was the problem of the succession. Charlemagne had three sons who survived to adulthood - Pepin, Louis and Charles the Younger. He also had four surviving daughters and half a dozen illegitimate children from various concubines. Succession to the Frankish kingdom was governed by the Salic law that had been followed by the dynasty that preceded the Carolingians, the Merovingians, which ruled that all close male relatives were eligible to inherit a portion of a dead man's lands, and the kingdom was no different in this respect. Charlemagne being emperor made this no different - his coronation, while undoubtedly an important event, did not mark the beginning of a new state and at a certain level Charlemagne may have seen the emperorship as essentially being his personal accolade. In 806, he drew up a plan for the division of the empire after his death. Pepin would rule as king over Italy and Bavaria. Louis' kingdom would consist of Aquitaine, Burgundy, Provence, Septimania and the Spanish March (the southern half of France plus Catalonia, basically). Charles the Younger would get what was left - that being essentially the entire northern half of the empire. Revealingly, no arrangements were made about who would inherit the imperial title. However, this plan never saw the light of day. When the great Frankish emperor finally breathed his last in 814, only one son was still alive, and that was Louis. Louis thus inherited an undivided empire - he had already been crowned king of the Franks and co-emperor by his ailing father the previous year.

Louis (see the coin of him below, modelled on Roman imperial coinage), or Louis the Pious as he would later become known (Ludwig der Fromme in German), was an idealist and a visionary who wanted to take the Carolingian reform programme of administrative and moral correctio (correction) to unprecedented levels. Like many people at the time, he subscribed to an essentially Old Testament view of kingship that saw the prosperity and security of the realm as dependent on the moral well-being of its rulers and people. Closely aligned with this, he firmly believed that as emperor he was responsible for the spiritual salvation of his people as well as their material security. What prevented his grand designs for going as smoothly as he might have hoped was the issue that had dogged the final third of his father's reign - and indeed, would dominate Carolingian politics for the rest of the ninth century - that of the succession. In 814, three of Louis' sons had already been fortunate enough to have made it past infancy - Lothar, Louis and Pepin. Unfortunately for Louis, he had to decide what to do with them. In 817 he drew up a document called the divisio imperii, which stipulated that Lothar was to get the imperial title and have most of the territories of the empire under his direct rule, while his brothers Pepin and Louis were to rule in Aquitaine and Bavaria respectively as subordinate kings (if they had sons they would inherit their kingdoms when they died, if they did not then they would revert to the emperor). But in 818, Louis' wife, the empress Ermengarde, died - the two of them had been quite close, and Ermengarde had closely advised Louis on many of his policies - and Louis reluctantly remarried, on the advice of his counsellors, to Judith, who gave him a son, Charles, in 821. This meant he had yet another son to provide for, as per ancient Frankish law and custom, and that meant chipping away at his other sons' inheritances, specifically that of Lothar, whose piece of the pie was by far the biggest as per the divisio imperii. Lothar and Pepin resented this between 830 and 839 Louis fought three civil wars against him - they were joined by their brother Louis for the third At some points things looked pretty dismal indeed for Louis - in 833 he was forced to perform a humiliating public penance and was technically deposed, but was fully re-instated as emperor the following year with widespread backing from the nobility. By 840, Louis was clearly on top and peace and order had been restored to the empire, but the stress of near-constant campaigning had taken a toll on his health and, after retreating to his summer hunting lodge near the palace of Ingelheim-am-Rhine, he died on 20 June 840, having forgiven his rebellious sons and confirmed Lothar as the new emperor.

What happened next was all-out civil war. Here, it was Lothar and his nephew Pepin of Aquitaine (so many Pepins to keep track of, I know), the son of the previous Pepin, trying to keep the empire together, while Charles (known to posterity as Charles the Bald) and Louis (known to posterity as Louis the German) were trying to carve out kingdoms of their own. On 25 June 841, a battle was fought between the two sides at Fontenoy-en-Puisaye in eastern France. A great slaughter followed. Andreas Agnellus, the bishop of Ravenna, estimated that 40,000 men died on each side - battlefield casualty statistics from early medieval writers are always to be taken with a pinch of salt, if trusted at all, but this was undoubtedly not a skirmish between a couple of thousand highly trained warrior retainers on either side (which is what some historians have argued to be typical of Carolingian warfare) but a major set-piece battle that really pitted the Frankish people against each other, and carnage ensued. For those who fought there, it was psychologically scarring. We are fortunate enough to know this because the Carolingian empire did have a mostly literate lay aristocracy, and two lay aristocrats who fought at the battle of Fontenoy expressed themselves eloquently on the matter - the historian Nithard and the poet Angilbert. Here is Angilbert's poem "Lament for Fontenoy." While it does contain some Old Testament imagery (as was standard for Latin literature at that time), one can nonetheless see genuine trauma in Angilbert's beautifully crafted verses, as genuine as that of any of the WW1 poets.

Fontenoy they call its fountain, manor to the peasant known,

There the slaughter, there the ruin, of the blood of Frankish race;Plains and forest shiver, shudder; horror wakes the silent marsh.Neither dew nor shower nor rainfall yields its freshness to that field,Where they fell, the strong men fighting, shrewdest in the battle's skill,Father, mother, sister, brother, friends, the dead with tears have wept.And this deed of crime accomplished, which I here in verse have told,Angibert myself I witnessed, fighting with the other men,I alone of all remaining, in the battle's foremost line.On the side alike of Louis, on the side of Charles alike,Lies the field in white enshrouded, in the vestments of the dead,As it lies when birds in autumn settle white off the shore.Woe unto that day of mourning! Never in the round of yearsBe it numbered in men's annals! Be it banished from all mind,Never gleam of sun shine on it, never dawn its dusk awake.Night it was, a night most bitter, harder than we could endure,When they fell, the brave men fighting, shrewdest in the battle's skill,Father, mother, sister, brother, friends, the dead with tears have wept.Now the wailing, the lamenting, now no longer will I tell;Each, so far as in him lieth, let him stay his weeping now;On their souls may He have mercy, let us pray the Lord of all.

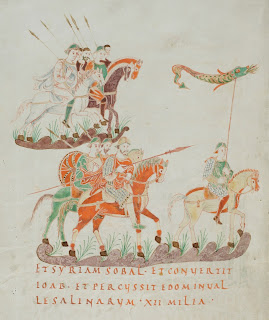

Overleaf: A much later (and more romanticised) depiction of the Battle of Fontenoy from a manuscript (dating to c.1460) of the Grand Chroniques de France, painted by the great French early renaissance painter Jean Fouquet.

In the end, the battle did have a clear winner - the divisionist side of Charles the Bald and Louis the German. Lothar and the imperialists were utterly crippled, and not long afterwards the emperor was forced to abandon the imperial capital, Aachen. In 842 Charles the Bald and Louis the German sealed their alliance at Strasbourg with mutual oath-taking, in which each of them swore oaths to each other's troops in the vernacular - Charles swore the oath before Louis' troops in a very early dialect of Old High German, while Louis swore the oath before Charles' troops in "the Roman language." The texts of the oaths is preserved and thus is a goldmine for historical linguists. The "Roman language" which Louis swore the oath in had clearly evolved quite some way from the spoken Vulgar Latin (as opposed to the high, literary Latin of Cicero, Caesar, Virgil, Ovid and Livy) of Roman Gaul into something that could now be called a Romance language. Some scholars have argued that the language of the text can be seen as the earliest written form of Old French. However, some more conservative linguists argue that it can't quite be considered Old French - it does not have any distinguishing features that would identify it as a forerunner to any of the literary dialects, either the Langue D'Oil of the northern French chansons de geste (songs of deeds in war), or the Occitan of Southern French troubadour fin'amour (what modern scholars call courtly love) lyrics, that attain written form when French vernacular literature gets going in the twelfth century. Indeed, there's one theory that the scribe who wrote the text of the oaths deliberately wrote in a kind of Gallo-Romance Koine, deliberately designed to be mutually intelligible to all regional dialects, like the Koine Greek of the New Testament. Below is the Gallo-Romance text:

Pro Deo amur et pro christian poblo et nostro commun salvament, d'ist di en avant, in quant Deus savir et podir me dunat, si salvarai eo, cist meon fradre Karlo, et in aiudha, et in cadhuna cosa, si cum om per dreit son fradra salvar dift, in o quid il mi altresi fazet, et ab Ludher nul plaid nunquam prindrai, qui meon vol cist meon fradre Karle in damno sit.

English translation (not my own): "For the love of God and the Christian populace and our joint salvation, from this day onward, to the best of my knowledge and abilities granted by God, I shall protect my brother Charles by any means possible, as one ought to protect one's brother, insofar as he does the same for me, and I shall never willingly enter into a pact with Lothair against the interests of my brother Charles."

The Treaty of Verdun and beyond

Lothar's position was incredibly fragile and so he agreed to come to a settlement with Louis and Charles. At Verdun in August 843 they agreed to divide the Empire into three between them (see the map below), but with Lothar keeping the imperial title. As you can see below, Charles' kingdom roughly corresponds to modern day France but plus Flanders and Catalonia and minus Alsace, Lorraine, the Rhone valley and Provence. Louis the German's kingdom is essentially West Germany minus some territories on the left bank of the Rhine and including some bits of modern day Switzerland, Austria and Slovenia. Therefore, some have seen this moment as being the genesis of France and Germany. Lothar on the other hand got what remained in the middle. Some would say that Lothar's kingdom was doomed from the start, arguing that it was simply too unwieldy to govern in an age when information could only travel as fast as a horse's hooves and with the Alps forming a significant obstacle between the north and south of his kingdom, that it was too ethnically and linguistically heterogeneous (a roughly 60:40 split between Romance and Germanic peoples) and that it was too vulnerable to attack from either side (I am kind of guilty of this tendency myself, in a certain meme I made, one featuring my all-time favourite animal). But I don't think there's any good reason to see Lothar's kingdom as any less viable than West and East Francia. Size was a problem for them too, and they were all inhabited by various different peoples each with their own dialects, laws and customs. While the inhabitants of Charles' kingdom north of the Loire identified as Franks and were subject to the laws of the Salian Franks, the inhabitants south of the Loire identified as Burgundians, Gascons, Visigoths (in Septimania and the Spanish March) and even Romans (I suspect that many old senatorial families still lingered in the aristocracy of southern Gaul) and were subject to Roman law - the Theodosian Code of 438 in Aquitaine and the Visigothic Breviary of Alaric II in Septimania and Catalonia - and the laws of the Burgundians. East Francia was a land of even starker contrasts, with the recently converted Saxons in the north, who had been making sacrifices to Odin and Thor in a time still within living memory, and still lived in a rough, frontier society governed by tribal customs, versus the cultured Bavarians in the south who took pride in having once been a Roman province and having converted to Christianity earlier than all the other peoples of East Francia; and its administrative and communications infrastructure were the least developed of the three kingdoms. Meanwhile, Lothar's kingdom had the highly agriculturally and viticulturally productive Meuse, Moselle, Rhine, Rhone and Po river valleys, making it very wealthy, as well as so many different places of ideological prestige including the imperial capital of Aachen, the old Lombard capital at Pavia, many great cities and bishoprics that went back to Roman times like Cologne, Trier, Lyon, Vienne, Milan and Ravenna and the great Carolingian family monasteries of Prum and Stavelot-Malmedy.

Above, all its crucial to remember that this was not an age of nationalism. The Carolingian nobility (what German historians call the Reichsaristokratie) continued to embrace a pan-Frankish identity and continued to own lands and act as patrons to monasteries in several different kingdoms - for example, Eberhard of Friuli (died 867), duke (military governor) of Friuli in the north east of the Italian kingdom, gave his lands in Italy and in the East Frankish kingdom to his eldest son Unruoch, his second eldest Berengar got his lands and monasteries in north western Lotharingia (modern day Wallonia region of Belgium) and his other two sons got his estates in northern West Francia. Church councils were still attended by bishops from across the Carolingian kingdoms, and flourishing intellectual networks drew in luminaries not only from all over the territories of the Frankish empire but also from the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Ireland and Christian Spain. And the kings themselves still kept to roughly the same royal ideology and carried on with the Carolingian reform project in their respective kingdoms.

What would do for Lothar's kingdom in the end was, yet again, dynastic problems. Lothar had three sons who survived to adulthood - Lothar II, Charles (so many Charles', I know, its confusing) and Louis (Louis was another name the Carolingians were hooked on calling their sons) - and when he died in 855 they proceeded to divide it between the three of them with the Treaty of Prum. Lothar II got the northern vertical strip from the North Sea down to the foothills of the Alps that soon became known for many a century to come as Lotharingia. Charles got the Rhone Valley and Provence. And Louis got Italy and the imperial title as Emperor Louis II. But biological good luck was not on their side. Charles died childless in 863 and his territories were shared between Lothar and Louis II. Lothar II quickly realised that his wife Queen Theutberga, whom he married in 855, was barren and so tried to divorce her and marry his concubine, Waldrada instead, but since the leading bishops of the ninth century were trying to assert ecclesiastical jurisidiction over marriage, and insisted on it as being sacramental and binding, Lothar had to fabricate an excuse in claiming that Theutberga had been engaging in incest with her brother, Hucbert. Hucbert offered to defend the reputation of him and his sister in trial by combat, and after Queen Theutberga was shown to be innocent in a trial by ordeal of boiling water (her hand healed rather than blistered a few days after being doused in boiling water) Lothar was forced to take her back. Lothar thus died without legitimate issue in 869 and his two uncles, Charles the Bald and Louis the German, briefly went to war with each other before signing the Treaty of Meerssen (see below), in which they divided Lotharingia between them.

Dynastic bad luck came next for Louis II in 875, who also died without male issue. Charles the Bald and Louis the German went to war again, this time over Italy, and by 880 it was annexed to the East Frankish kingdom. Dynastic bad luck then hit the West Frankish branch of the Carolingian family real hard - after Charles the Bald died in 877, his son Louis the Stammerer reigned for only two years and his two teenaged sons from his first marriage, Pepin (still more Pepins) and Carloman, ruled the kingdom jointly for three years and then with Carloman as sole ruler for two years. When Carloman died in 884, his only heir was his five year old half-brother, Charles the Simple. The West Frankish nobility didn't want a child king, especially since this the point in time at which the Viking invasions were at their most devastating, so they invited Charles the Fat, the youngest son of Louis the German who had already hoovered up East Francia and Italy by outlasting all his brothers, to become king of West Francia. For four years, the Carolingian Empire was reunited under a single emperor. But Charles the Fat was a uninspiring leader with too many talented subordinates, and he too had failed to procure a legitimate male heir. So when he died of a stroke in January 888 after facing a rebellion in East Francia from his illegitimate nephew, Arnulf of Carinthia, the empire broke up again, this time forever, with the aristocracies of West Franica, Burgundy, Provence and Italy all electing kings from amongst their own ranks.

In the very long term, the Treaty of Verdun would indeed be very significant. West Francia and East Francia would, in the long-run, despite all the territorial configuration and reconfiguration all the way through the ninth century and beyond, prove to be quite durable political units and would, no later than the thirteenth century, develop into the distinct and recognisable cultural entities of France and Germany. Meanwhile, the old Middle Kingdom of Lothar would become a battleground between the rulers of the two kingdoms bestride it. I won't go into the details of what happened in the tenth century, since I'll cover them in other posts. Suffice to say that from c.1000 - 1643 the border between France and Germany/ the Holy Roman Empire lay squarely at the river Meuse, with Verdun itself being a border fortress, but after the Thirty Years' War concluded in 1648 France, which was among the victorious powers, got given various towns and fortresses east of the Meuse. Louis XIV fought a series of wars to bring the French border to the left bank of the Rhine, and also to conquer the Hapsburg Netherlands (modern day Belgium), in which he managed some further territorial acquisitions, including Alsace and French Flanders (the area around Lille and Dunkirk). Successive French leaders thereafter tried to achieve the same result - Louis XV managed to annexe all of Lorraine by 1766, and over the course of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792 - 1802) the First French Republic managed to bring its borders all the way to the left bank of the Rhine. Indeed, the areas under direct rule from Paris in the reign of Emperor Napoleon I essentially corresponded to West Francia plus the kingdom of Lothar (see map below).

After Napoleon's defeat in 1815 the French border was again set where it is now. But in 1871, Alsace and Lorraine were lost to the newly unified German Empire. They would only be regained by France after WW1, a war whose Western front essentially encompassed the old kingdom of Lothar II and its borderlands with West Francia (see map below).

France would again lose Alsace and Lorraine to Germany with Hitler's invasion in 1940, and it was only in 1945 that the border between France and Germany was finally set where it is now, with its security and that of the Low Countries being guaranteed by the formation of the European Economic Community soon after. The European Economic Community would of course develop into the European Union. Interestingly enough, the EU's headquarters are located in Brussels and Strasbourg, both of them located in the old middle kingdom of Lothar II, and the EU annually awards the Charlemagne prize to those who they think merit it for the promotion of a pan-European identity. So one might say the story of the rise and crisis of the Carolingian empire is a central foundation myth to the European Union and its ideals.